First Cubesats to Visit Another Planet Will End Mars Mission Today

Two tiny trailblazing satellites hitched a ride to Mars with NASA's InSight lander in May, becoming the first small satellites to leave Earth's friendly neighborhood — but today (Nov. 26), they are nearing the end of their mission.

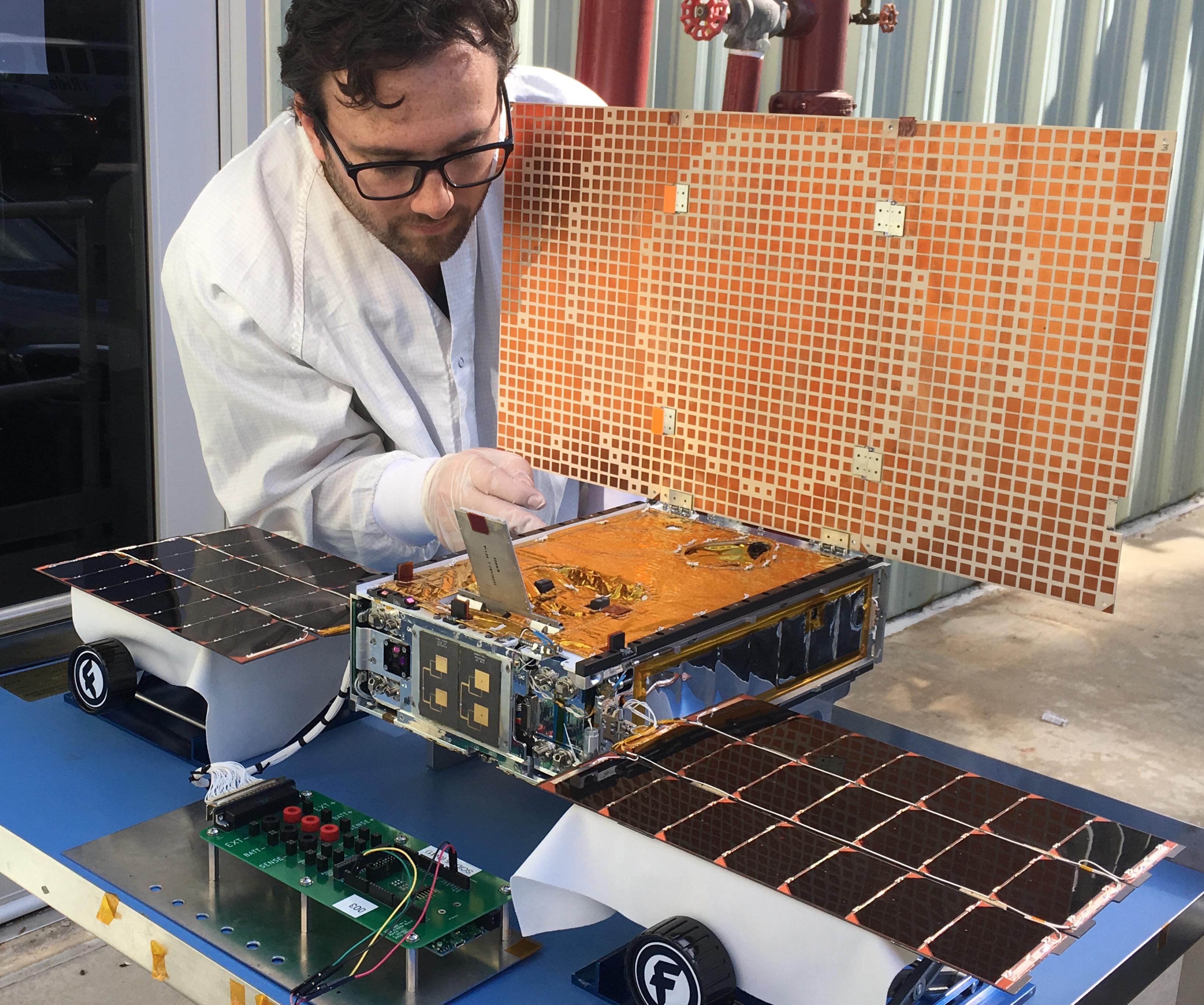

Those satellites make up the $18.5 million Mars Cube One mission, or MarCO, a technology-demonstration project that piggybacked on the InSight geology mission to test the limits of briefcase-size cubesats that weigh in at just 30 lbs. (13.6 kilograms) apiece.

"They've actually completed all of their primary objectives in terms of demonstrating technologies we want to use," John Baker, program office manager for the MarCO mission, told Space.com. "I'm very pleased with the results of the mission so far." [NASA's InSight Mars Lander: Full Coverage]

Over the course of the mission, the little spacecraft have captured the hearts of the engineers on the team, who nicknamed the pair WALL-E and EVE after the robotic characters in the Pixar movie "WALL-E." In an iconic scene from that film, the pair use puffs from a fire extinguisher to dance through space — and depending what kind of fire extinguisher the fictional robots were using, that could be exactly the same fuel the MarCO satellites rely on. In space, releasing small amounts of compressed gas is enough to steer such small satellites.

Although the spacecraft are twins, with NASA flying two for redundancy's sake, the satellites don't quite behave identically, taking after their namesakes. "WALL-E has been a little bit trickier to control, and his cold-gas system has been a little less predictable, whereas EVE has been very straight-shot and very well-behaved," Baker said.

While fire-extinguisher fuel makes for an endearing means of propulsion, it isn't powerful enough to pull the MarCO satellites into orbit around the Red Planet. They'll merely fly by Mars, skimming within 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) of its surface.

But the pair won't simply be sightseeing during their flyby; in fact, their cameras will be disabled. Instead, if all goes according to plan, the satellites will gather InSight's broadcasts during its perilous entry, descent and landing process and relay them back to Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If MarCO succeeds at this task, it will eliminate hours of anxious waiting on the part of the InSight engineers. "Because of all of that delayed gratification, we decided we'd bring a couple of stalkers with us called the MarCO spacecraft," Tom Hoffman, NASA's InSight project manager, said during a news conference held on Nov. 21. (That said, InSight doesn't rely on MarCO; if the relay pair fails, larger orbiters around Mars will be waiting to perform the same job.)

At every step of their journey, the MarCO satellites have done their team proud, proving just how small technology can get and how far cubesats can go. "MarCO has crammed a lot of new technologies and new capabilities into a small volume," MarCO-B Mission Manager Anne Marinan said during the Nov. 21 news conference. "The team is thrilled with how it's done so far."

But is today really the end of the line for MarCO? Maybe not. The satellites will skim past Mars and continue orbiting around the sun, tugged a little off their previous path by the planet's gravity. Next, the team will need to use the satellites' incredibly tiny radio systems to pinpoint where each MarCO is before establishing any additional destinations.

"Once they pass Mars, we'll do some tracking to figure out where they ended up," Baker said. "Then, we'll see if there's any option for what they could do in the future in terms of a convenient asteroid they could fly by or something like that."

But even if the pair just keeps floating through space, MarCO engineers can still learn more from the satellites' ongoing journey. Right now, engineers aren't even sure how long cubesats can stay healthy in interplanetary space, because the MarCO satellites are the first to venture out so far.

"We want to find out how long they'll actually last," Baker said. "We put these things together relatively quickly. We didn't use traditional processes that we do for the larger missions."

Visit Space.com today for complete coverage of the InSight landing on Mars.

Space.com managing editor Tariq Malik contributed reporting to this article. Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.