Space Could Fry Your Phone: How Space Tourists Can Protect Their Electronics (and Data)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Michael D. Shaw is a biochemist and freelance writer. A graduate of the University of California, Los Angeles, and a protégé of the late Willard Libby, winner of the 1960 Nobel Prize in chemistry, Shaw also did postgraduate work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Based in Virginia, he covers technology, health care and entrepreneurship, among other topics.

Before the space-tourism industry takes flight and passengers start taking their electronic devices into orbit, there had better be a way for travelers to protect their digital data from the harsh environment of space.

Between the radiation and the effects of microgravity, the typical smartphone, tablet or laptop may malfunction before you have the chance to tweet your amazing photos of Earth. Add NASA's worries about hackers intercepting communications and even commandeering control of satellites in space, and our electronic devices and the data they contain become even more vulnerable. [Photos: The First Space Tourists]

If and when your personal electronic devices succumb to these vulnerabilities in space, whether it's during a suborbital flight on SpaceShipTwo or an extended stay at a luxury space hotel, there will likely be no resident IT expert aboard your spacecraft. And without a working mobile device, you'll have a hard time calling tech support back on Earth.

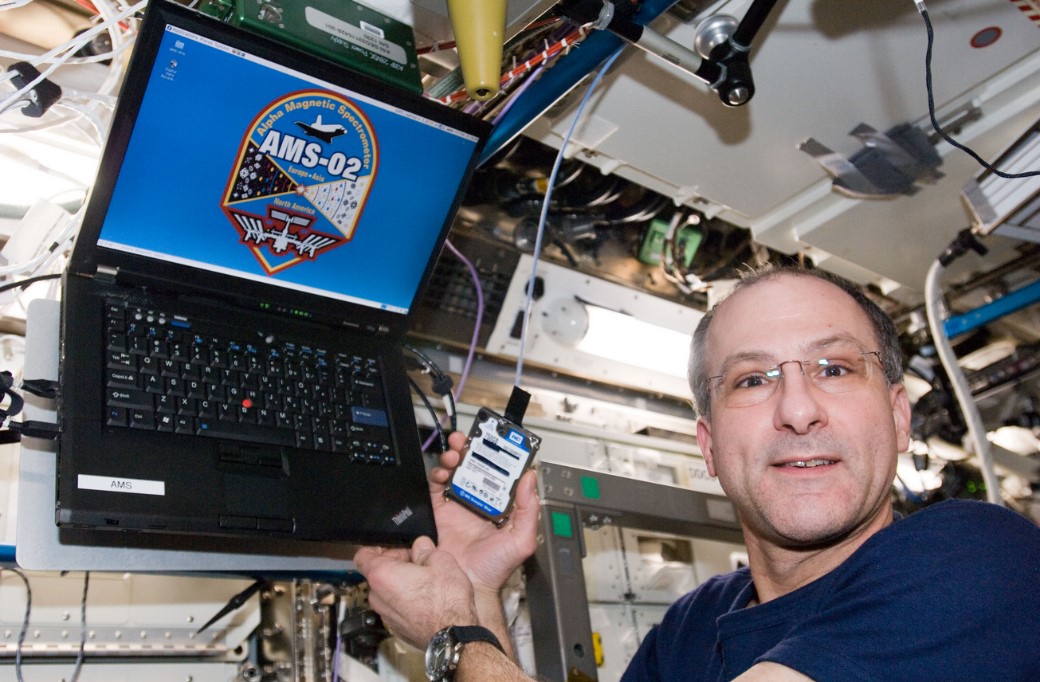

How, then, do astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) send and safeguard their data? In a word: carefully. According to Backup4all, which services the laptops at the space station, data protection is essential not only to the research and science experiments astronauts perform at the orbiting lab, but also to the information they see and share on social media.

As the ISS orbits Earth 16 times a day (or about once every 90 minutes), crewmembers back up their data to 13 destinations, including external hard drives and the same cloud-storage providers that many of us use on Earth. Those include Google Drive, Dropbox and Microsoft OneDrive. That data involves experiments concerning cancer research, "cool-flame extinction" and the use of a Robonaut in high-stress conditions, among other things.

If backup policies were not in place, NASA and its international partners at the space station would risk losing "time-sensitive, mission-critical data, like information about the crew's health, the status of the station's systems, results from onboard science experiments, as well as every single social media post and interview," NASA officials said in a statement. It would be hard for NASA's public outreach to succeed without the breathtaking pictures of space the agency shares with its social media followers. Picture, too, the space station's Twitter feed without its 2.3 million followers.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now, picture yourself without access to your own data and pictures. A malfunctioning smartphone can be frustrating enough on Earth. But how would you feel if your smartphone stopped working while you were hundreds of miles away from the planet, making it impossible for you, as a space tourist, to beam pictures and messages down to Earth? You could avoid these future "first-world problems" by keeping data-backup tools at the ready.

Here on Earth, 140,000 hard drives crash every week in the United States alone, according to the cybersecurity news website CSO.com. Recovering a crashed computer can cost upward of $7,500, with no guarantee of success. Even worse, every year about 70 million smartphones fall victim to theft, whether they're physically stolen or digitally hacked, according to a study from the Kensington Computer Products Group. The study found that the cost of losing a laptop or other mobile electronic device can greatly exceed the cost of the device itself "thanks to lost productivity, the loss of intellectual property, data breaches, and legal fees."

The good news is that the ISS can be the ultimate symbol of data protection. It already is a symbol of the triumph of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Translating that symbol into a call to action should be a national priority. Creating a call to action "is a design challenge, to be sure," said Janil Jean, director of overseas operations for LogoDesign.net. "It is not, however, an insurmountable one. Not when it is easier — at the moment — to find a 'no smoking' sign than it is to find a sign that warns against not leaving data vulnerable to loss or theft."

I agree with that statement, just as I believe in the value of the mission of the ISS. That value has many denominations, from the actual work that crewmembers do every day to the data that serves as a digital record of the research these men and women perform on behalf of humankind.

We should emulate their example by doing the practical thing, which is also the smart thing: treating data as a personal commodity and a public good that is too precious to squander, too powerful to sacrifice and too potent to surrender — and that is equally as vulnerable in space as it is on the ground, if not more vulnerable.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.