Planets in Two-Star Systems Could Boast Life-Friendly Moons

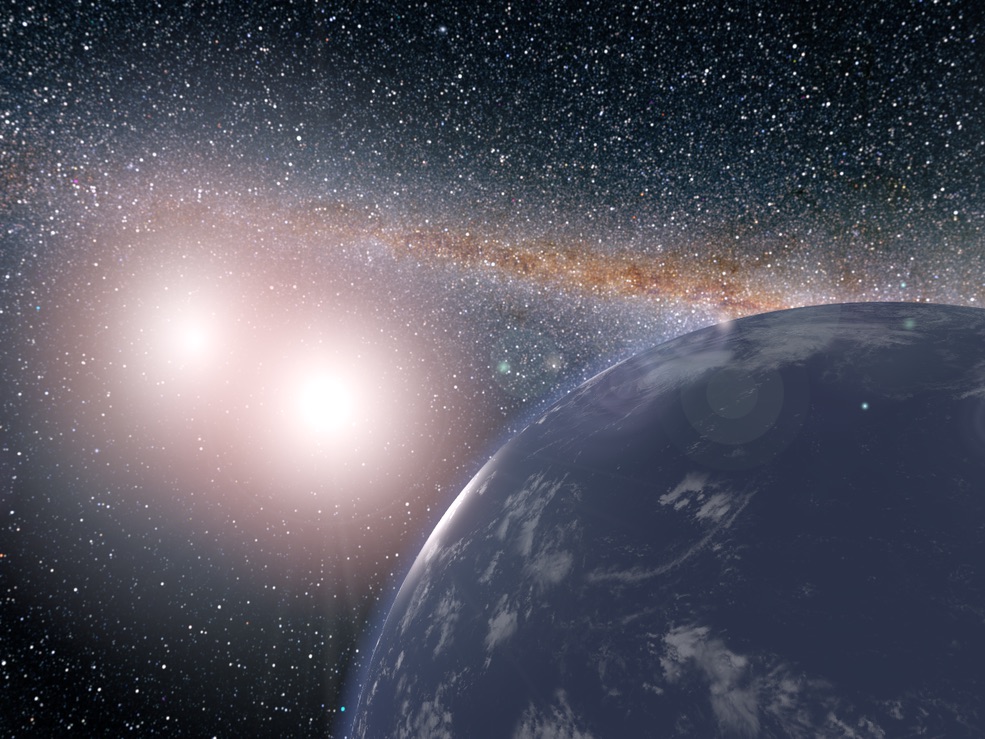

The icy and rocky worlds around giant planets make up some of the most potentially habitable regions of Earth's solar system. So far, only one potential moon has been found orbiting a planet around a distant star, but given the wealth of moons orbiting planets around Earth's sun, it seems likely that more exomoons may remain unseen. New research suggests that planets orbiting pairs of stars, as depicted by the well-known "Star Wars" world Tatooine, could hold on to their moons, creating sites for life to evolve.

Double-star systems can create a challenge in stability that their single-star cousins avoid, however. In both types of systems, the stars move around slightly, potentially disturbing any orbiting planets and their moons. When two stars are dancing together, it increases the odds that the stars will knock away a planet, as well as its moon.

"Stability is the first requirement for habitability," Adrian Hamers, a planetary theorist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, told Space.com by email. With his colleagues, Hamers modeled the stability of the 10 confirmed exoplanets orbiting binary stars that have been identified by NASA'sKepler Space Telescope. The researchers calculated the regions of stability where exomoons could be detected using future instruments. [Photos: NASA Discovers Real-Life 'Tatooine' Planet with 2 Suns]

"If the orbit of the exomoon is not stable, then, in extreme cases, it will be flung out of the system," Hamers said.

Stable moons

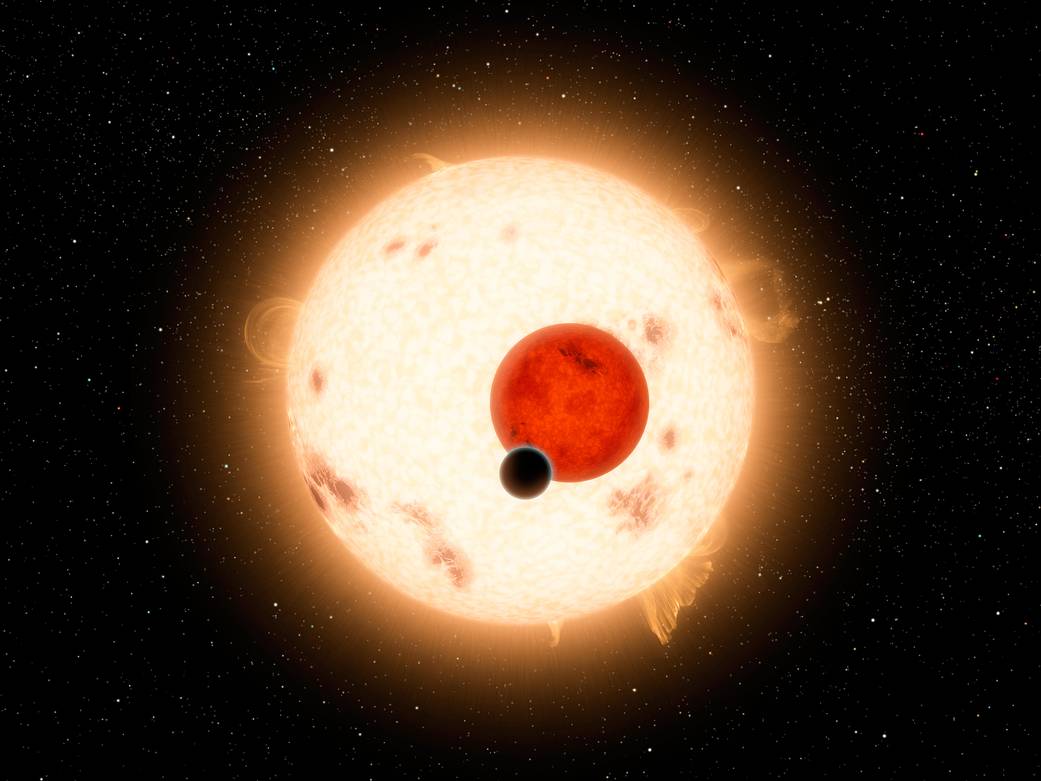

Over nearly a decade of study, Kepler identified 10 exoplanets in orbit around nine pairs of stars. The planets lie close to their stars, zooming around in no more than seven Earth days. Each pair of stars is in a tight configuration, separated by only about a tenth of the distance between the Earth and sun, a number known as one Astronomical Unit (AU). The planets themselves orbit their stars' centers of mass at a distance of about one AU, making these worlds circumbinary. (Planets can also orbit a single star in a binary pair; if the pair is far enough apart, the planet may act more like it is circling a single star.)

While the exomoons of planets that orbit a single star is awell-studied phenomenon, Hamers said, less work has been done for exomoons in binary systems. A handful of circumbinary worlds have been discovered using other telescopes, but the researchers in the new study were particularly interested in the newfound Kepler planets.

"We were curious which orbits of exomoons around these circumbinary planets would be dynamically stable," Hamers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists ran multiple simulations of the moons of planets around stellar pairs. Results showed that stable simulated moons remained close to their planets, at about 0.01 AU apart, so that these moons were less affected by the gravity of the stellar pairs. Moons were also more stable when they circled more massive planets. The angle of the moon's path around the planet compared to the planet's path around the suns proved important, as well. When a moon circled at a 90-degree angle compared to the planetary path, the moon oscillated widely before becoming unstable, crashing into the planet or, on rare occasions, one of the stars.

What might it look like to stand on the moon orbiting a planet with two stars in the sky? That would depend strongly on the moon's orientation and rotation period, Hamers said. If the moon resembles the moons of Jupiter, its "day" will likely span several Earth days. The tight orbits of these exomoons mean they should whip around their giant planets over about 10 Earth days, he said.

"During the 'day' on the exomoon, there will be two stars visible in the sky, separated by about 40 degrees, which will noticeably move during the course of the 'day,'" Hamers said. "Also, there will be times that the binary stars eclipse each other, [with] only one star visible for a limited amount of time."

If all three objects travel along the same plane, the planet itself will obscure the stars roughly every 10 days. If they are tilted in relation to one another, however, eclipses may be avoided.

Although the new research did not directly hunt for exomoons, the findings could help aim future hunts for the tantalizing objects. By determining the regions around a circumbinary planet where an exomoon would be unable to survive, Hamers said, this research can help scientists discount ambiguous signals. Such misleading signals could be effects created by stellar activity or star spots.

The new findings also reveal the limits on exomoon stability around double stars depending on the ratio of the planet’s mass to that of its stars. "This relation likely applies to any circumbinary system," Hamers said. However, he did add the caveat that the team focused on Kepler binaries; the researchers didn't thoroughly investigate outside binaries.

Telescopes such as NASA's recently launched Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite and the upcoming European CHEOPS and PLATO spacecraft may be good for hunting down exomoons, Hamers said.

The research was detailed Nov. 1 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter@NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us on Twitter@Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd