What's Next for NASA's Voyager 2 in Interstellar Space?

WASHINGTON — Voyager 2 has passed an incredible milestone in its journey to explore the solar system by entering interstellar space, but neither its travels nor its science are ending any time soon.

During a news conference held at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union today (Dec. 10), scientists and engineers said that while they're excited about crossing the boundary, both Voyager 2 and its twin probe have plenty of life left in them. Their continuing science will help shed light on how particles flowing off the sun collide with the particles on the interstellar wind beyond.

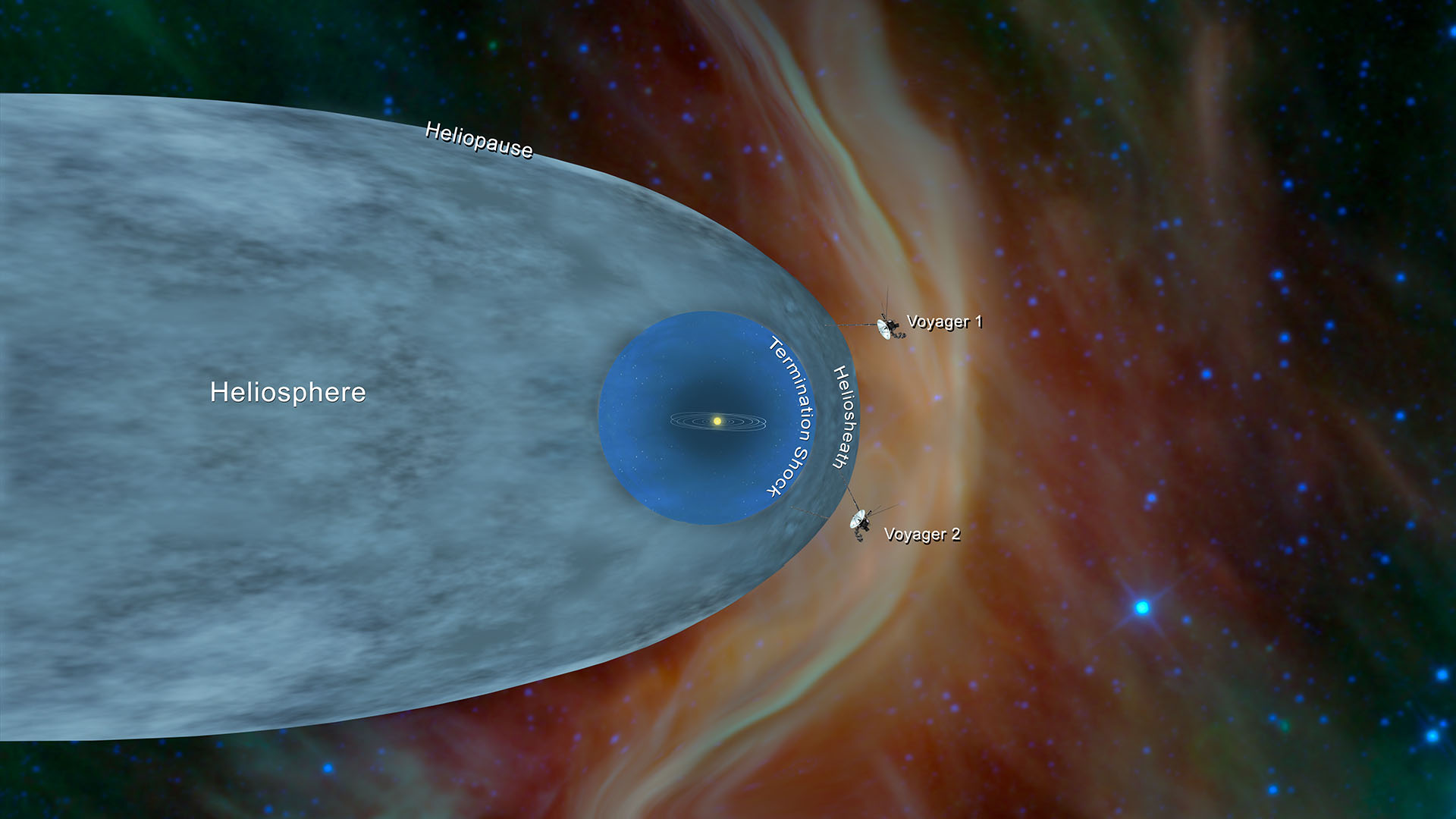

The twin Voyager probes are the first spacecraft to date that humans have sent to this boundary, called the heliopause. "Nothing is really like taking those steps, taking that journey into the region to really visit it for yourself," Nicky Fox, head of solar science at NASA, said during a news conference. [Voyager 2: 40 Photos from NASA's Epic 'Grand Tour']

That journey could last for years if all continues to go well. "Both spacecraft are very healthy, if you consider them senior citizens," Suzanne Dodd, project manager for the Voyager Interstellar Mission, as the mission has been rebranded, said during the news conference.

The key challenge for the remainder of spacecraft operations is coping with the gradual loss of heat and power. Voyager 2 is currently operating in temperatures of just about 38.5 degrees Fahrenheit (3.6 degrees Celsius), and for each year that passes the spacecraft's power production drops 4 watts.

That means that eventually, the team will need to turn off instruments in order to coax as much science as possible out of the spacecraft before they can no longer operate. "We do have difficult decisions ahead," Dodd said.

Right now, she estimates that the twin probes can operate for at least five, perhaps 10 more years with this gradual decay of science data coming back. Dodd said that her own goal for the mission is to coax a full 50 years of exploration out of the spacecraft since their launch in 1977. "I think that would be fantastic."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Although Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause first, Voyager 2 offers a couple of new opportunities. It carries an operating plasma science detector, whereas its predecessor's stopped working decades ago. And because of the current stage of the solar cycle, Voyager 2 may find itself crossing the heliopause again as the sun's bubble expands around us.

Even once the heliosphere is well and truly in Voyager 2's rearview mirror, it will be able to tell scientists about the flood of interstellar wind pushing against the heliopause and about the local bubble surrounding the heliosphere. That means catching sight of lots of galactic cosmic rays, the incredibly high-energy atoms of a whole range of elements that are careening across the universe at nearly the speed of light.

"Galactic cosmic rays act as tiny messengers of our local galactic neighborhood," Georgia Denolfo, an astrophysicist at NASA who is not involved with the Voyager mission, said during the news conference. "We're able to actually look at the galaxy through the clouded lens of our heliosphere and now take a step outside with Voyager and for the first time contemplate the vistas of our local galactic neighborhood."

Not only could Voyager 2's continuing journey tell us about our own neighborhood, but its insights may also shape how we understand exoplanets. Each alien solar system is nestled in its own equivalent of a heliosphere, pushing out against its own local interstellar space. How precisely that balance plays out could shape how hospitable these planets are to life.

Although neither Voyager's instruments will last forever, the two spacecraft themselves will continue their plodding course across the solar system. Within about 300 years, they will reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud, the sphere of comets surrounding our solar system. Crossing that field will take somewhere in the realm of 30,000 years.

Once the Voyager probes leave our solar system entirely, they'll settle into a long, lazy orbit around the heart of the Milky Way galaxy for millions, if not billions of years, humanity's first emissaries into the vastness around us.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.