What's the Weather On Mars? How NASA's Insight Lander Will Find Out.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NASA's new Mars lander isn't quite ready to probe the Red Planet's interior yet, but it's starting to get the lay of the land on the surface — and in the atmosphere. The InSight lander is already deploying its powerful meteorology package to monitor the Red Planet's weather.

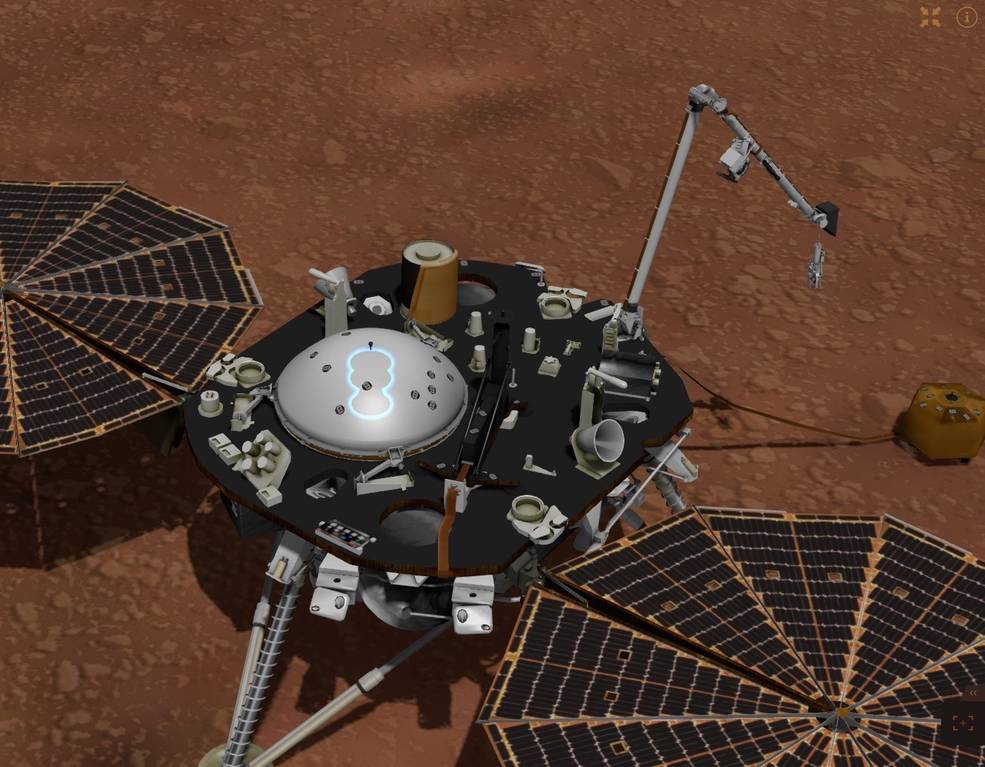

InSight touched down on the Martian surface Nov. 26, and since then it has been carefully analyzing its environment and setting up its sensitive suite of instruments. The mission's seismometer still sits on the lander's deck, measuring InSight's vibrations rather than the planet's, and the heat-sensing mole remains undeployed as well. But the lander's meteorology suite is already gearing up to measure the pressure, temperature and three-dimensional wind patterns on the Red Planet.

Part of that suite — the pressure sensor — played a starring role in new "sounds from Mars" recently released by the InSight team. That sensor and the seismometer both caught the vibrations of wind rushing across the instrument deck and the seismometer's protective cover. [NASA's InSight Mars Lander: The Mission in Photos]

"We're still getting our feet underneath us on this mission, but it's fun to put out some of this early stuff that keeps us excited," said Don Banfield, a co-investigator on InSight's science team and researcher at Cornell University.

"It's actually a bit surprising how much science you can extract from these instruments, even when they're in a configuration they aren't finally intended to be," he told Space.com.

When the sensors are out in their final configurations, the pressure sensor and other weather measurements will play a critical role measuring atmospheric "noise" that needs be removed from the seismometer readings. And as they do, they will provide top-notch measurements of weather patterns at the Martian surface.

"This is a pretty extreme pressure sensor compared to anything we've sent to Mars before," Banfield said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On Earth, changing pressure heralds changing weather systems, and even though the overall pressure is much lower on Mars — about 0.75 percent Earth's pressure at sea level — the effect is similar. "Mars has seasons, just like Earth, and it has high-pressure and low-pressure systems that roll around the planet, just like Earth," he said.

Even though the pressure systems are less intense near the equator, where InSight is situated, the lander's gear is sensitive enough to eventually pick up faraway changes, Banfield said. And it's already picking up evidence of something closer to home: The dust devils and vortices that spin up as sunlight heats the ground, which also occur on Earth. Eventually, the pressure sensor should also be able to pick up something called infrasound — the low-frequency sound waves that propagate through the air due to different atmospheric phenomena, which is also how the pressure sensor captured the sounds of the planet's wind in those early-released results.

But there are more intriguing things to be measured that way, as well: "If we get lucky and a meteor enters Mars' atmosphere close to above the lander, it will probably explode and make a shockwave, and we may be able to detect that shockwave with the pressure sensor," Banfield said.

Another instrument that is already returning data is the Temperature and Wind for InSight (TWINS) tool, which extends two long booms facing in opposite directions to sense wind and temperature. Each has a little heated die surrounded by sensors, which measure the heat loss and the direction the wind pulls the heat, as well as attachments that measure the air temperature.

"They're kind of like, you lick your finger and the cold side is the windy side — it's the same sort of physics," Banfield said. "Except on Mars, it has to be a very sensitive measurement, because the air density is down by this factor of 100 or more, and so the air doesn't actually drag away that much heat from your wet finger or the probe. It has to be very carefully calibrated." [NASA's New Mars Lander Takes 1st Selfie, Scopes Out Workspace]

As those calibrations take place, TWINS is slowly gaining the capability to measure winds at all hours of the Martian day and night. At the moment, the data is only usable for part of the day. But eventually, it will be able to return readings constantly.

Continuous reporting is standard for weather stations on Earth, but this is a rare chance for such consistent data from the Martian surface.

"This may not be obvious to everybody, but because of data-volume limitations, in the past, to understand the climatology of Mars and meteorology of Mars well enough, we have usually measured 10 to 15 minutes every hour or two, and we have just turned the instruments off for the time between that," Banfield said. "That's great, if what you want to do is get an overview picture of what the meteorology's doing, but if you want to, say, understand exactly what wind speed it took to move some sand grains on the surface, or kick up some dust, you need to be measuring the winds all the time."

While Earth's weather and climate are dominated by the effects of water through humidity and clouds, Mars' are tied to the planet's dust storms reflecting sunlight and trapping radiation, Banfield said — and this precise measurement can help researchers understand the wind power needed to kick up dust, or why small dust storms grow bigger or even go global.

InSight's weather measurements can also be compared to those of the Mars Science Laboratory on the Curiosity rover, just about 350 miles (560 kilometers) away on the Martian surface, to get a more accurate picture of how high- and low-pressure systems move across the planet. They can also add depth to measurements from the Mars Climate Sounder instrument aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which directly measures weather systems but can only see down to about 5 or 10 km above the surface, missing "where most of the action is," Banfield said. InSight can provide a view of what's happening right on the ground.

When Space.com spoke to Banfield Dec. 11, the team had just gotten the first data back when the short-period seismometer and pressure sensor were on at the same time. "We were able to see the pressure signature of a dust devil and the ground-tilt signature of that same dust devil," he said. "It's working as the theory would predict, but I guess I didn't expect it to be quite so clear or dramatic — it's pretty cool."

"Nature usually surprises you one way or another — the first time we hear one of these weird infrasound sources, I'm going to be very excited," he added.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.