Christmas Comet 46P Is Making the Season Bright (and Green) for Scientists

Just in time for Christmas, the latest apparition of a comet shines like a beautiful ornament in the sky — a delightful green-shrouded treat for amateurs and scientists alike.

On Dec. 16, Comet 46P/Wirtanen made its closest approach to Earth in more than 20 years, back when digital cameras and laser astronomy were in their infancy. With much more advanced tools, astronomers today brought the celestial visitor under unprecedented scrutiny.

At the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, a group of scientists led by Boncho Bonev (a physicist at American University) were giddy with anticipation. [Amazing Photos: Brilliant Comet 46P/Wirtanen Wows Stargazers]

"It is very exciting because the comet is so close and sufficiently bright for detailed astronomical studies," Bonev said in a statement from the observatory. "Comet Wirtanen is only 30 lunar distances from our planet, meaning that it is about 30 times the distance to the moon. That is nothing compared to the vast distances astronomers typically work with."

The team received prized telescope time between Dec. 16 and 17, just when closest approach occurred. Their timing perfectly coincided with the relaunch of the newly upgraded Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSPEC) instrument. NIRSPEC has more pixels operating with greater sensitivity, allowing astronomers to spot much fainter objects in the sky.

"We installed more sensitive detectors, replacing the digital imaging devices, along with other mechanisms and optics, with brand new ones to give the instrument a new lease of life," Ian McLean, the University of California at Los Angeles physicist and astronomer who really pushed for the commissioning of NIRSPEC in 1999, said in the same statement.

It's too early to say what NIRSPEC caught on Wirtanen, because science results often take months to analyze at the least. But the potential for fresh insights drove the team — especially in their hunt to find prebiotic molecules (water, ammonia, hydrocarbons), or the precursor ingredients to life.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Though our goal is to characterize Comet Wirtanen's chemical composition, there is always the possibility to see something unexpected or discover something new that will raise new questions to address. That's what makes science so exciting," Bonev said.

Building blocks of life

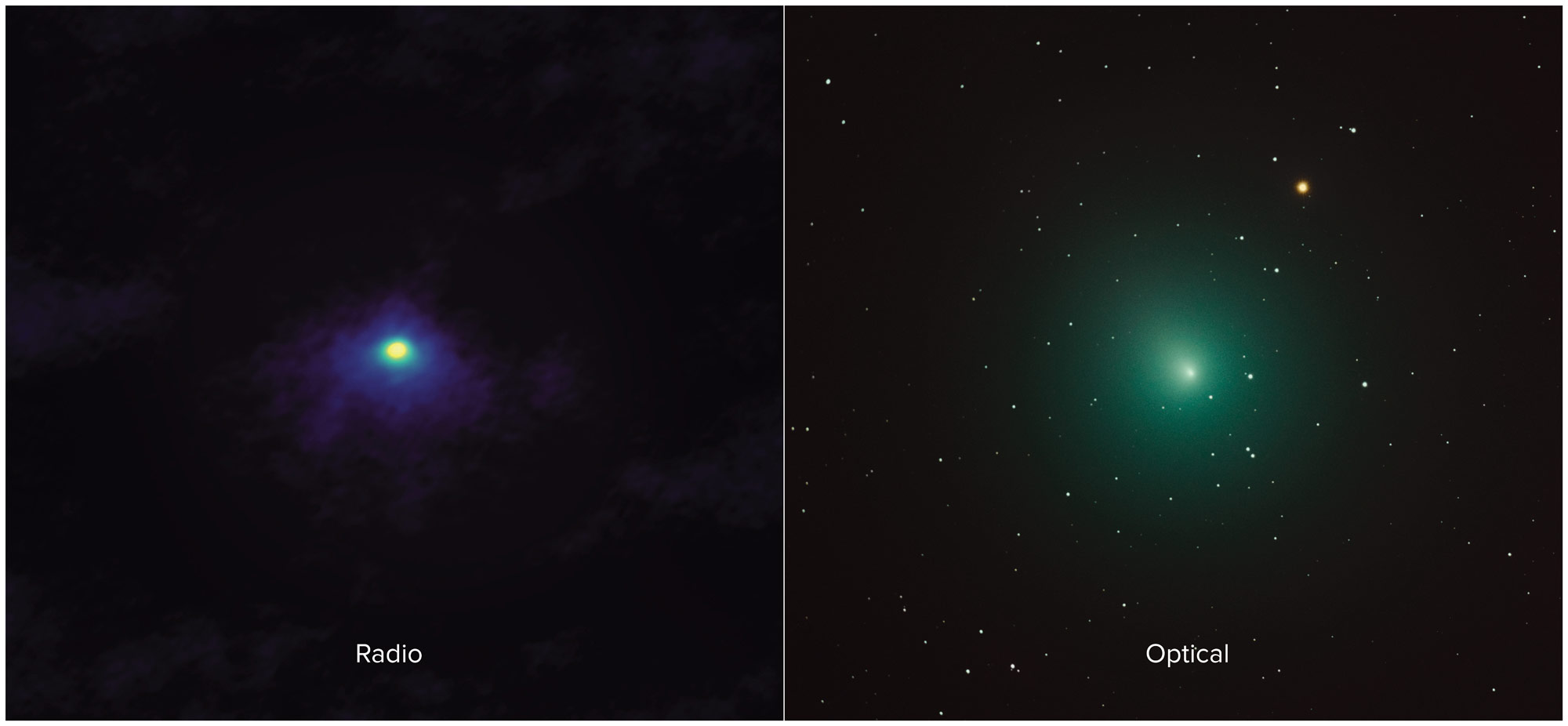

In the opposite hemisphere to Keck, Chile's Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) also watched the comet's passage just before its closest approach, on Dec. 2 and Dec. 9. The team's goal was to glimpse the gassy envelope surrounding the nucleus — a region more properly known as the coma.

"This comet is causing a stir in the professional and amateur astronomy communities due to its combined brightness and proximity, which allows us to study it in unprecedented detail," NASA's Martin Cordiner, who led the team making the ALMA observations, said in a statement from the observatory. "As the comet drew nearer to the sun, its icy body heated up, releasing water vapor and various other particles stored inside, forming the characteristic puffed-up coma and elongated tail."

ALMA zoomed in on the heart of Wirtanen, capturing the glow emitted from an organic molecule called hydrogen cyanide. Organics catch scientists' attention because these carbon-chained molecules are the building blocks of life on Earth.

Early images released from ALMA show the hydrogen cyanide clustered in a somewhat lopsided pattern inside the coma, but more detailed results will be released in future science papers. The design of ALMA's 66 individual radio receivers allow astronomers to gaze at the sky in millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths. That zone of the electromagnetic spectrum can reveal things invisible to the human eye, such as comet comas or planetary systems shrouded by dust. By looking at extremely far-away objects, ALMA also peers back in time to our universe's earliest galaxies.

As for Wirtanen, it's slowly journeying away to Jupiter in its orbit until it circles near our planet once more in 5.5 years. That sounds like a long time until you begin to compare Wirtanen's orbit with more famous comets such as Halley, which takes about 75 years to circle the sun. Certain comets from the more distant Oort Cloud can take thousands of years or even tens of thousands of years for a repeat visit, researchers have calculated.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.