New Horizons Spacecraft Makes New Year's Day Flyby of Ultima Thule, the Farthest Rendezvous Ever

LAUREL, Md. — Wow, what a way to ring in the new year.

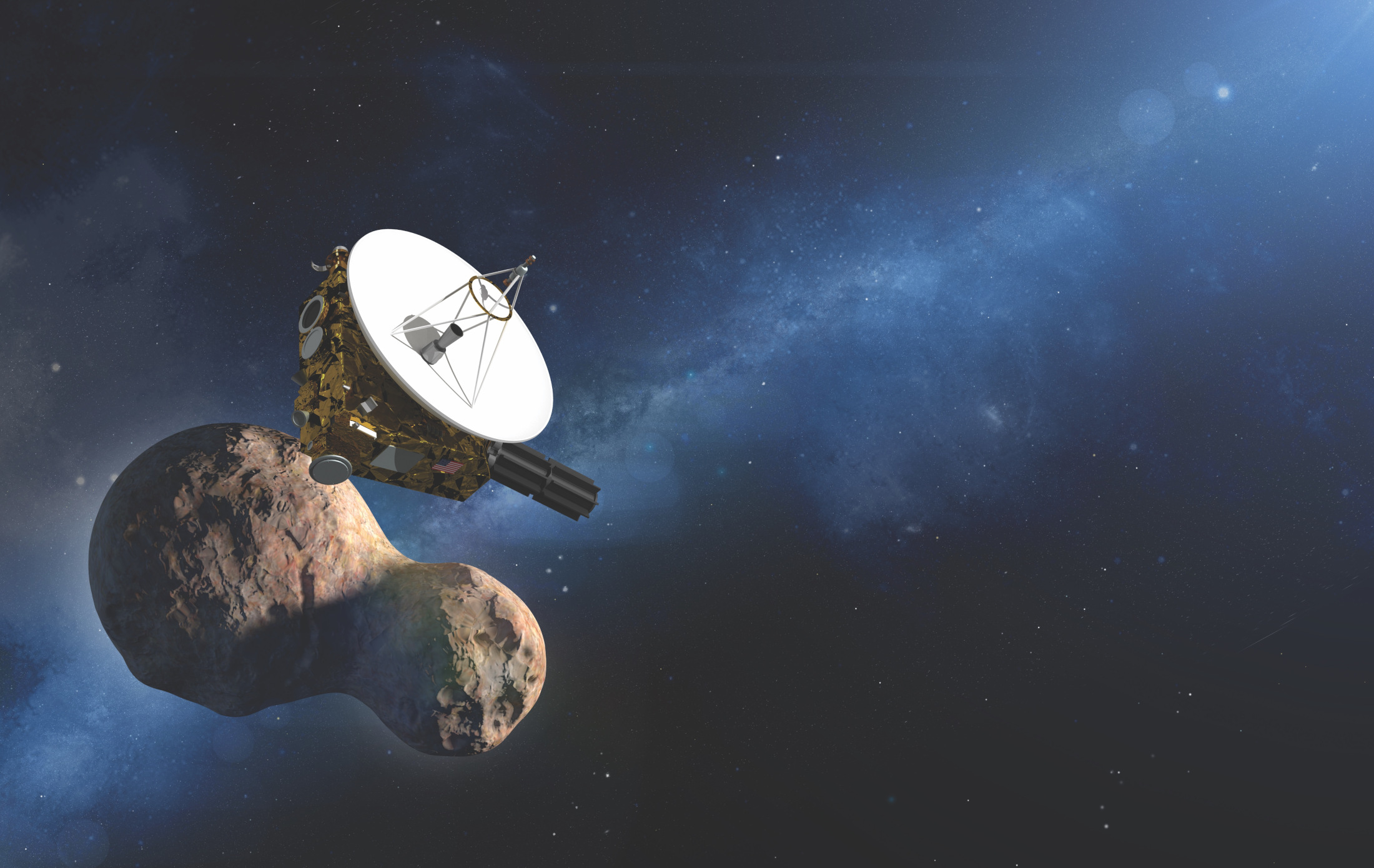

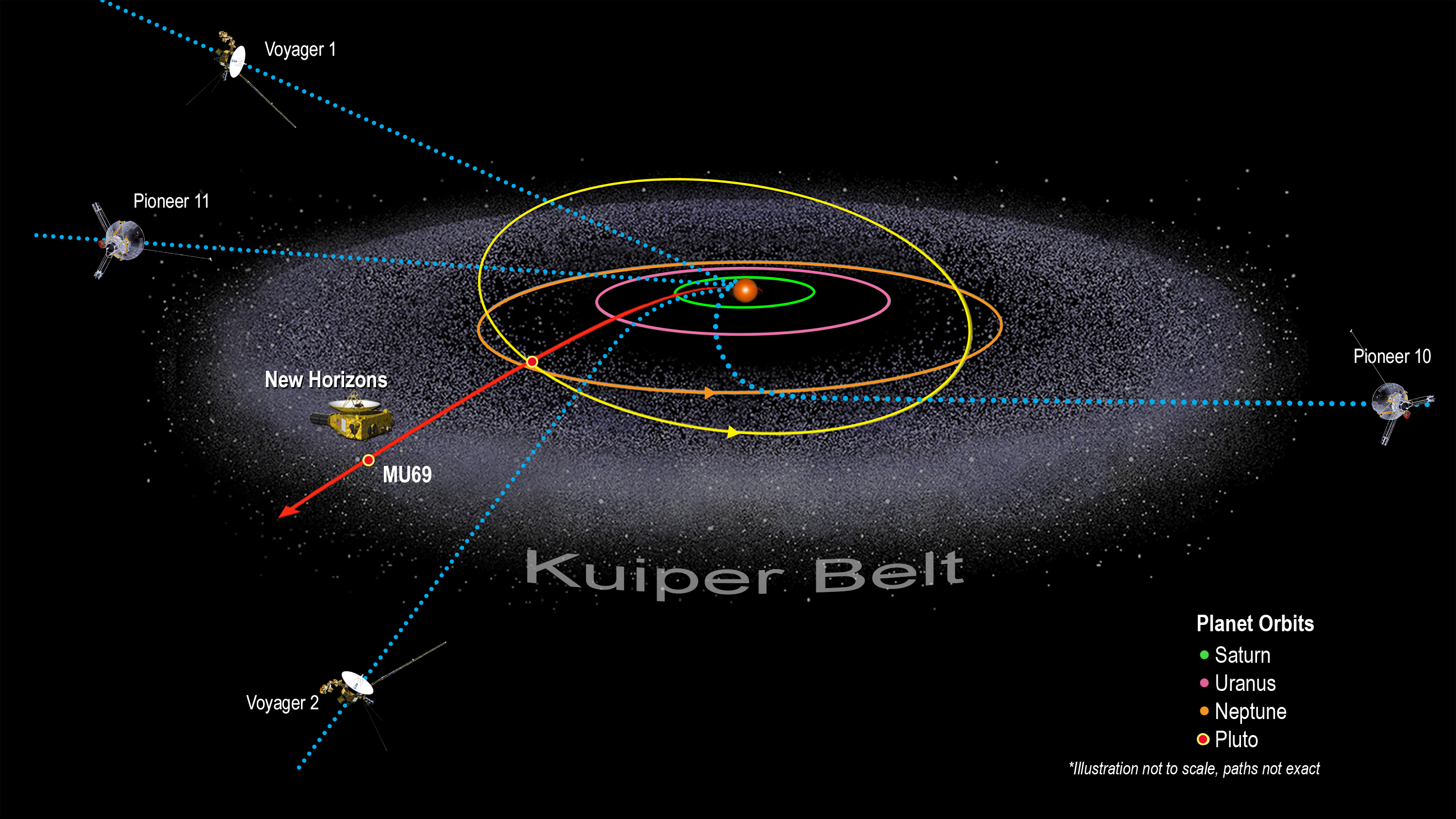

As the world celebrated the start of 2019, scientists with NASA's New Horizons spacecraft partied with them. But the bigger celebration came just over 30 minutes later, when New Horizons made history with the flyby of Ultima Thule, a mysterious object 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion kilometers) from Earth in the Kuiper Belt, home to frozen relics left over from the birth of the solar system. It's the farthest flyby of an object in our solar system; and the second rendezvous for New Horizons, which visited Pluto in July 2015.

"We set a record! Never before has a spacecraft explored something so far away," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, said after the flyby today (Jan. 1). "I mean, think of it. We're a billion miles further than Pluto, and now we're going to keep going into the Kuiper Belt. [New Horizons at Ultima Thule: Full Coverage]

New Horizons flew by Ultima Thule at 12:33 a.m. EST (0533 GMT), hurtling past at a mind-boggling 32,000 mph (51,500 km/h) as it captured the first close-up views of a Kuiper Belt object. The cosmic rendezvous occurred so far from Earth, it'll took more than 6 hours for a signal from New Horizons to reach Earth. At about 10:30 a.m. EST, the first signal from New Horizons was received at its mission operations center here at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

"We have a healthy spacecraft," said Alice Bowman, mission operations manager for New Horizons. "We've just accomplished the most distant flyby. We are ready for Ultima Thule science transmission."

And oh, the party. With news of signal confirmation, a standing ovation by mission team members and invited guests broke out in an auditorium here. And of course, there was the New Year's Eve bash.

"Nerding out on New Year's Eve"

To celebrate New Horizons' visit to Ultima Thule, the mission team threw an epic New Year's Eve party. Hundreds of guests — including science team members, dignitaries, reporters and their families — packed a meeting hall here to ring in 2019, and then cheer for the flyby. As Stern said, everyone was "nerding out at New Year's Eve."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Are you psyched?" Stern asked the crowd as they cheered just seconds before the flyby. "Are you jazzed?"

Among those guests were Rep. John Culberson (R-Texas), actor Chase Masterson of "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine," as well as astrophysicist (and Queen lead guitarist) Brian May. May even debuted a new original song — the aptly named "New Horizons" — at midnight to celebrate.

"To me, it is the incredible newness of it," May, a New Horizons mission team member, told reporters before the flyby. "This is going way beyond where anyone has gone before, literally."

The celebration occurred in the midst of a partial government shutdown, which shuttered much of NASA's public outreach for the Ultima Thule flyby. But NASA and JHUAPL were able to stream live webcasts and photos of the flyby. Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's associate administrator for science, even received special dispensation from NASA chief Jim Bridenstine to attend.

"I think it is fitting that this flyby of Ultima Thule is at the interface of the 60th anniversary of Explorer 1 [the first U.S. satellite] in 2018 and the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 in 2019," Zurbuchen said in an email that Stern read aloud Monday. "To me, this milestone for New Horizons is full of everything that NASA and NASA science is about."

Another NASA mission also hit a milestone on New Year's Eve. The space agency's sample-return probe OSIRIS-REx officially began orbiting its target asteroid Bennu on Monday (Dec. 31), making it a banner 24 hours for planetary science.

Voyage to the Kuiper Belt

It's been a long road to Ultima Thule for New Horizons.

NASA launched the $700 million nuclear-powered spacecraft in January 2006 on a mission originally aimed at Pluto. That mission was an astounding success, with New Horizons zipping by Pluto and its five moons on July 14, 2015, revealing the first-ever detailed photos of the dwarf planet (including its adorable heart).

But even before New Horizons reached Pluto (which itself is in the Kuiper Belt), mission scientists were looking to the next target. In 2014, mission scientist Marc Buie of SwRI discovered Ultima Thule (then known only by its official name, 2014 MU69) using the Hubble Space Telescope and a new destination was set. [Ultima Thule in Photos: Images from the Kuiper Belt]

The key draw of Kuiper Belt objects is their primordial nature. They are time capsules, Stern said, preserving the earliest conditions of the solar system at temperatures near absolute zero.

"The object is in such a deep freeze that it's essentially preserved from its initial formation," he added. "Everything that we're going to learn about Ultima, from its composition to its geology to how it's assembled, are going to teach us about the original formation conditions of the solar system."

And scientists have a lot to learn. They've only managed to glean tantalizing clues about Ultima Thule since its discovery in 2014.

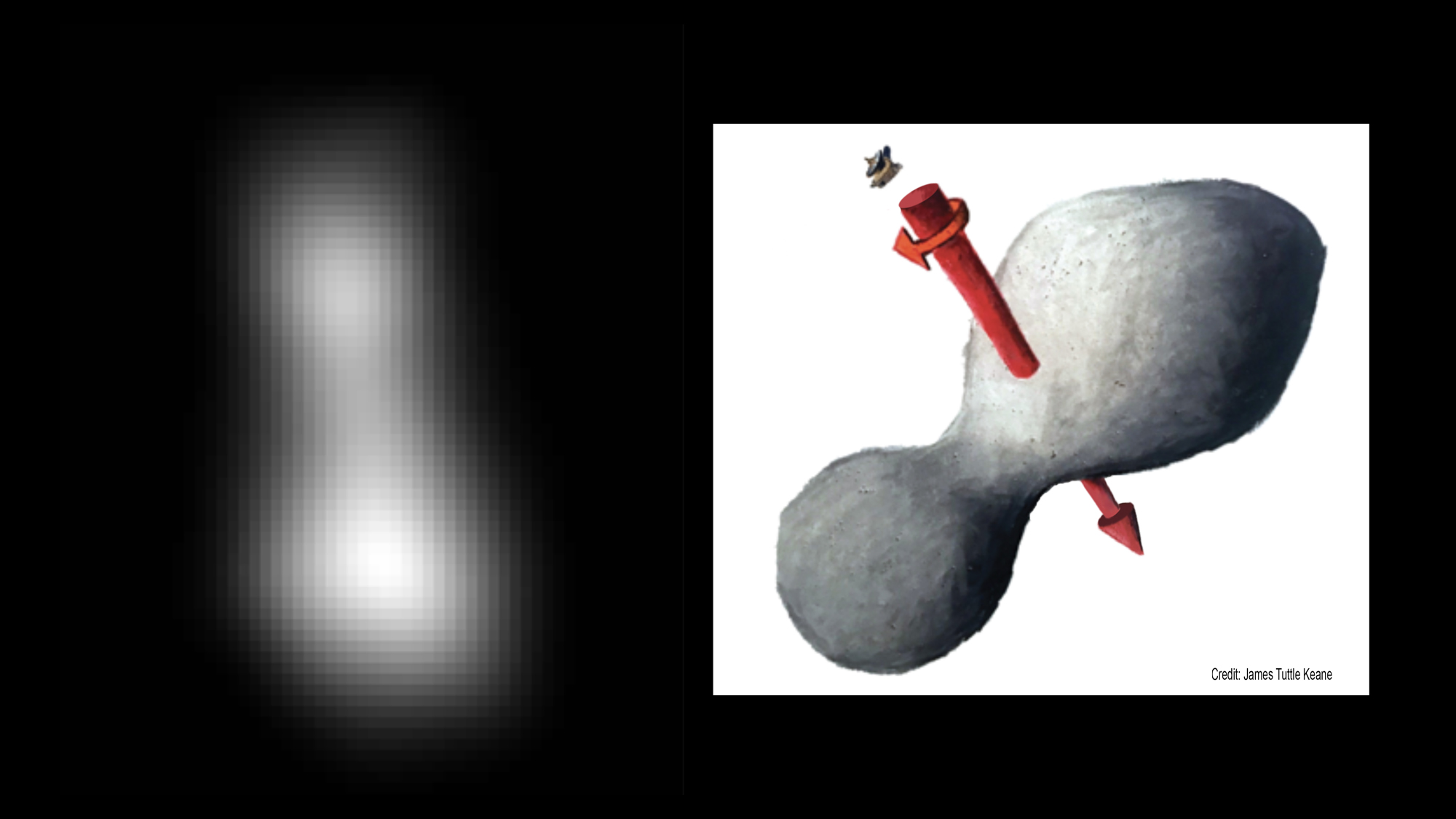

In Hubble telescope photos, Ultima Thule appears to have a reddish hue. Exactly why is unknown. Early observations suggested that it may actually be more than one object, a binary, but more recent images (including one taken on Saturday, Dec. 30) have hinted that this isn't so. Ultima Thule appears be a single object, mission scientists said.

"We know it's not round," said deputy project scientist John Spencer of SwRI before the flyby. Recent images show Ultima Thule as an elongated, oval-shaped object.

In fact, Ultima Thule may look like a bowling pin, with two lobes connected by a center mass. A photo taken by New Horizons on New Year's Eve just before closest approach clearly shows two lobes and an elongated shape, an improvement on Sunday's view, scientists said.

But exactly how fast does it spin (estimates vary between 15 and 30 hours)? Does it have craters, or a smooth surface? Does it spout dust? Could it host moons or rings or something altogether unexpected?

"This is unknown exploration; anything is possible," Spencer said. "Anything is possible out here when you're exploring a new class of world that you haven't seen before."

Only a detailed analysis of New Horizons' images and other data from its seven instruments will tell the tale, scientists said.

"We are going to change what we know about the Kuiper Belt, literally overnight," Stern said.

Another flyby ahead?

It will take about 20 months for New Horizons to beam back all of its images and other observations of Ultima Thule. That's because it has just a small 15-watt transmitter to beam a vast amount of data home.

"I am in awe that we can even do this," Stern said. "The spacecraft has a 15-watt transmitter on it...that's a quarter of a light bulb. And we're receiving it from 4 billion miles away."

But the New Horizons team won't be idle during that time. Scientists are actively searching for a third Kuiper Belt object for New Horizons to potentially visit.

If that target is found soon, and if it gets funding approval from NASA, the team could get the green light for another flyby, in a year that will also celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, the first by astronauts.

"Fifty years ago, the first humans walked on another world, the moon, as a result of NASA," Stern said. "And NASA was the first space agency in the world to reach every planet in the solar system, from the closest planets — Venus and Mars — to the farthest, Pluto. And now we're out exploring even further."

Editor's note: This story, originally posted at 12:43 a.m. EST, was updated at 12:57 p.m. EST with new images of Ultima Thule from New Horizons.

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.