The Far Side of the Moon: How China's Chang'e 4 Can Crack Lunar Mysteries

On Wednesday (Jan. 2), China's Chang'e 4 mission successfully carried out the first-ever soft landing on the moon's far side, a region full of celestial mysteries.

Often mistakenly called the "dark side" of the moon (it does receive sunlight), the far-side region is the back of Earth's natural satellite that is perpetually turned away from our planet. Chang'e 4 will collect data so that scientists can better understand the evolution and formation of the moon.

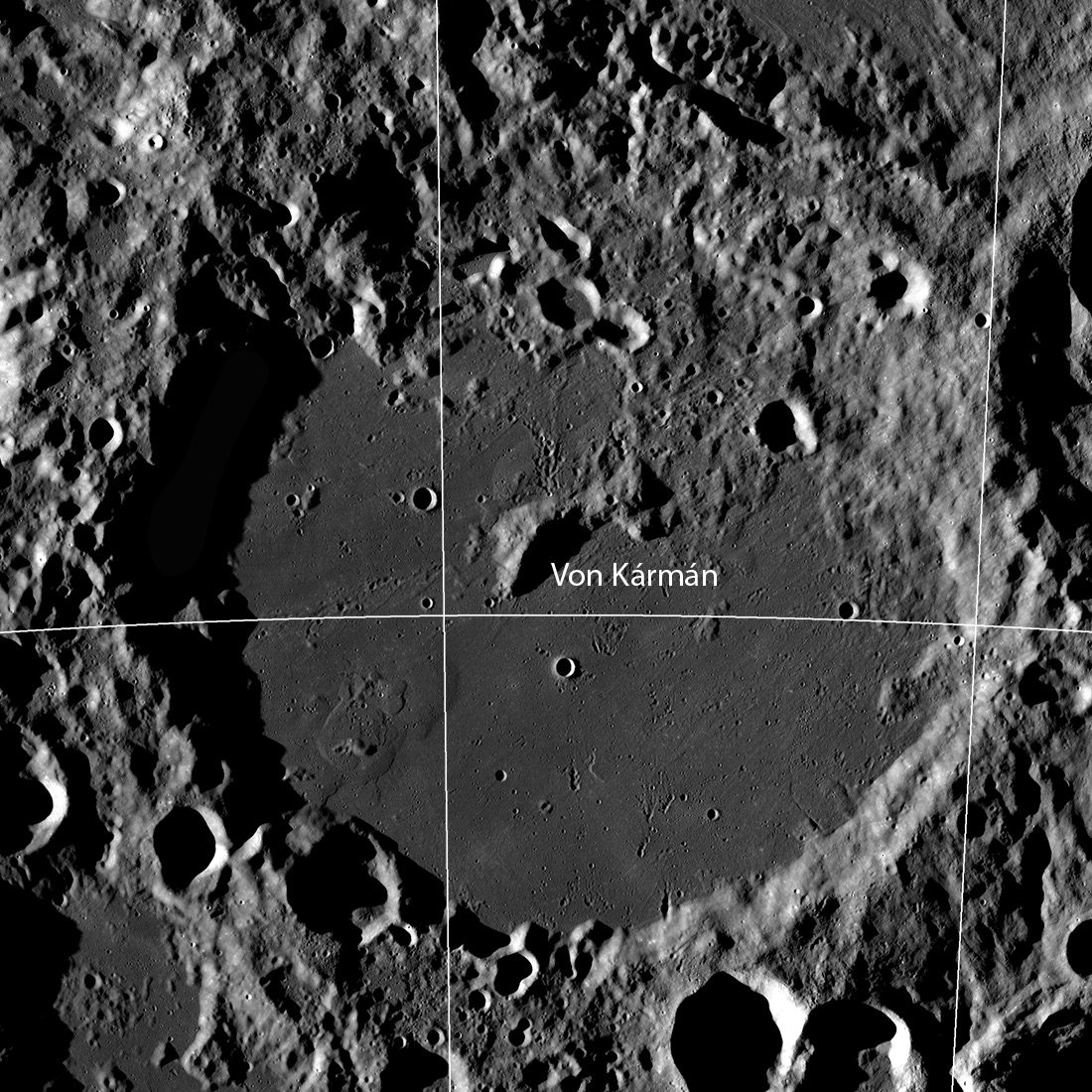

Chang'e 4 landed over a special, possibly insightful location. Von Kármán crater, a 115-mile-wide (186 kilometer) feature, is full of scientific potential. It's home to igneous rock that may reveal clues about the moon's internal structure, and includes fascinating volcanic constructs (mantle deposits that resemble the shape of Earth's cinder-cone volcanoes), secondary craters made by the ejecta of earlier impacts, landslides and more. [China's Chang'e 4 Returns First Images from Moon's Farside Following Historic Landing]

The formation of the moon may reveal clues about how the solar system evolved, and the basalt deposits found near the Chang'e 4 landing site may help scientists glean more about the past.

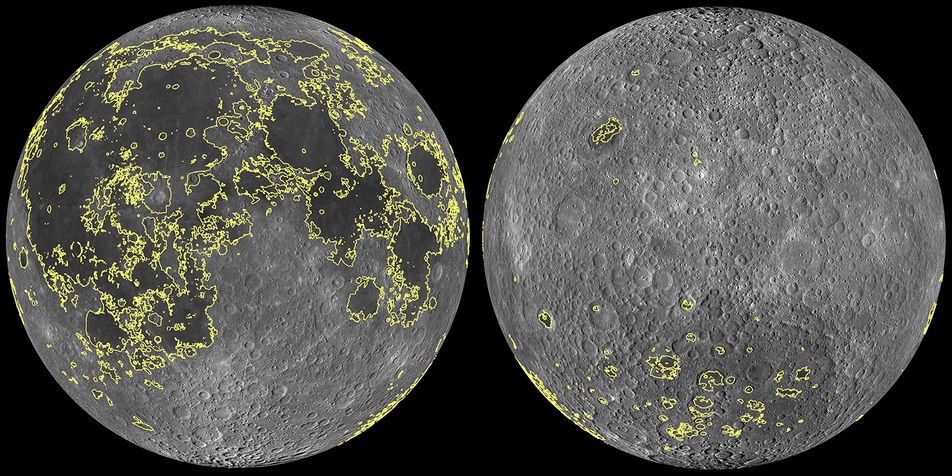

And one mystery is why the near side and the far side of the moon differ so drastically.

For one, the crust is much thicker on the far side, relative to the near side. "We don't really know why at this point," Mark Robinson, principal investigator with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC), wrote in an email to Space.com. LROC captures high-resolution black-and-white images and moderate resolution multispectral images of the lunar surface. "Samples from key locations on the nearside and farside would really help us tackle this question," Robinson said, and the Chang'e 4 mission could measure the mineralogical composition of these rocks.

The lunar far side also contains less potassium and phosphorus than the near side does, which puzzles scientists.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In addition, the far side's surface generally looks rougher, with the exception of Von Kármán crater, research scientist Heather Meyer, who works with the LROC science team, wrote in an email to Space.com.

"The nearside is dominated topographically by the presence of large basins that have been filled to the brim with basaltic lava flows (or mare deposits), making it relatively flat and smooth and erasing any small- to mid-sized craters that may have formed," Meyer said.

But the moon's other side looks very different.

"However, the farside contains fewer large impact basins, and the few that do exist on the farside are not completely filled with lava flows," Meyer said. "As such, the farside displays a broader range of elevations and a lot more small- to mid-sized craters, making the surface appear more rough."

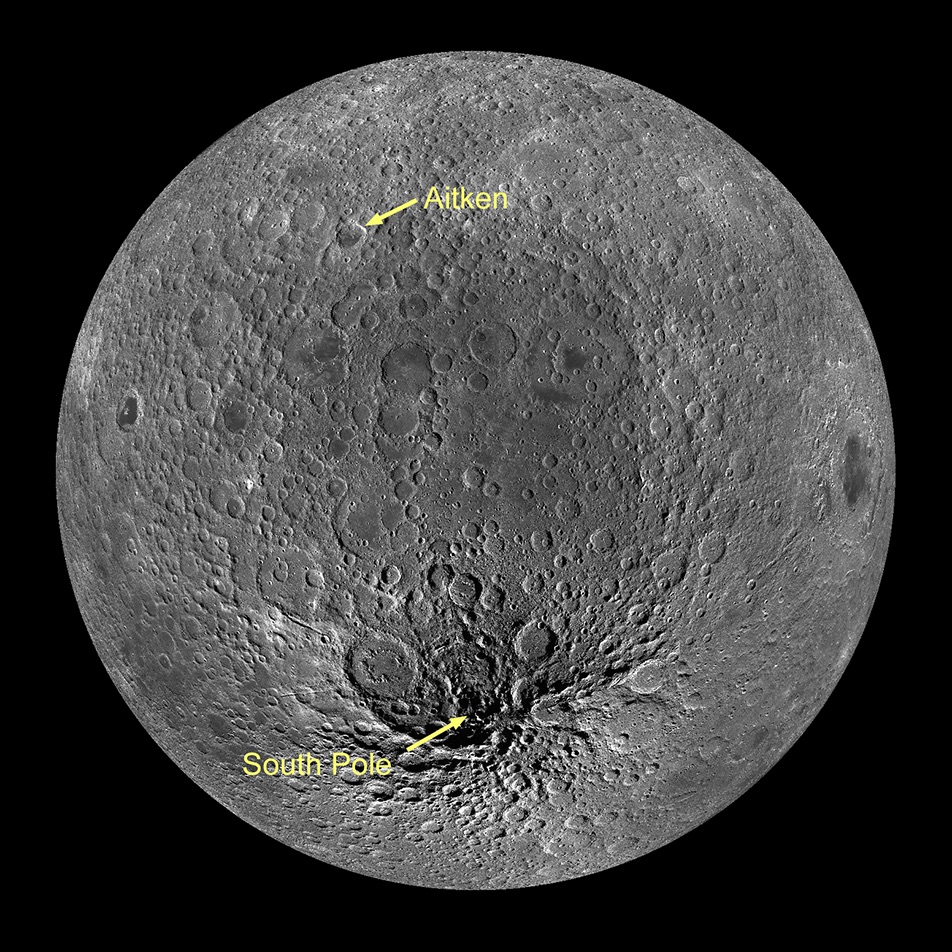

The one neighborhood that doesn't fit this trend is the South Pole-Aitken basin, the region that contains Chang'e 4's new home, Von Kármán crater. The basin, like the near side of the moon, is covered in a smooth layer of lava deposits.

The South Pole-Aitken basin is over 1,367 miles (2,200 kilometers) wide, making it the largest observed impact structure on the moon, and according to the LROC team, it's possible that the collision penetrated through the entire crust.

According to Meyer, this basin is one of the most ancient and poorly understood lunar terrains. Chang'e 4 is a "step in the right direction" toward answering questions about how the basin's formation affected the thermal and compositional evolution of the moon's far side, she added. Some of those mysteries include how old the SPA basin is and how its formation affected volcanism in the far-side crust.

The Visible Near Infrared Spectrometer (VNIS), Panoramic Camera (PCam) and Lunar Penetrating Radar (LPR) instruments on Chang'e 4 will aid in making scientific interpretations about the mysterious far side of the moon.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.