How to Tune a Star System: Alien World Complicates Harmony of Multiplanet System

This must be good vibes: Researchers have identified a sixth planet orbiting the first star system discovered by the crowdsourcing project Exoplanet Explorers. A new video visualization, released yesterday (Jan. 7) at the 2019 American Astronomical Society conference in Seattle, shows how the new planet's orbit harmonizes with those of the other five.

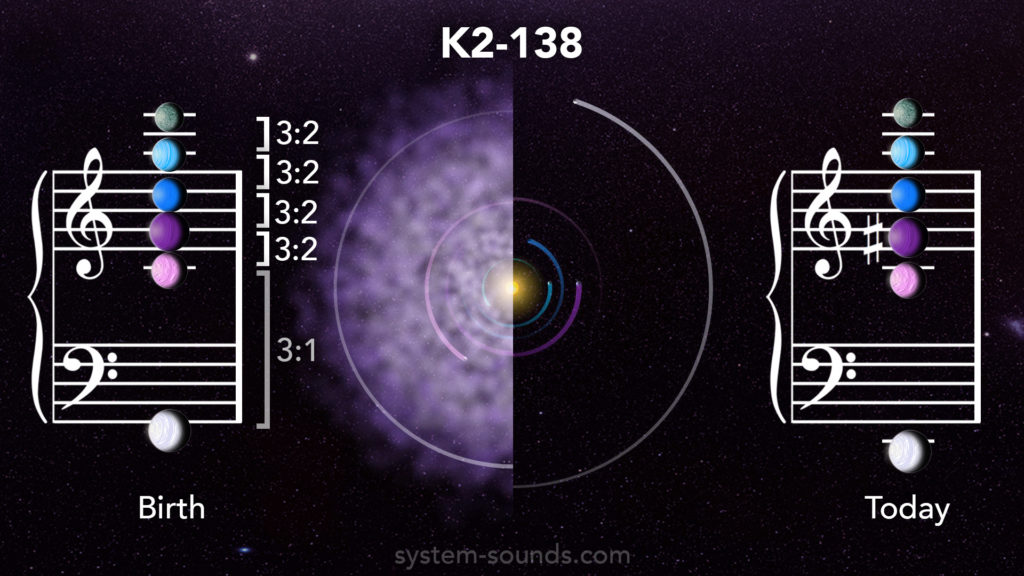

The star system K2-138 whirls almost 600 light-years from Earth, and the first five planets discovered in the system orbit at a unique pace: For every three times an inner planet orbits the star, the next-farthest-out planet orbits close to two times.

The newly discovered planet, confirmed using data from NASA's Spitzer telescope, orbits much farther out — but if there were planets in between, it could also follow that pattern (three inner-planet orbits to two outer-planet orbits between neighbors). Regardless, it's an intriguing addition to the close-orbiting system. [Exoplanet Symphony: Listen to TRAPPIST-1 Worlds' Orbital Music]

The innermost five planets are "the longest undisturbed near-3:2-resonant system that we've ever discovered," Kevin Hardegree-Ullman, a researcher at the California Institute of Technology, said during a press briefing at the conference. Not to mention, "this is only the ninth exoplanet system [discovered] with six or more planets." The system was identified last year by the Exoplanet Explorers project, which uses the crowdsourcing platform Zooniverse, in data collected by the Kepler telescope's K2 mission.

The host star is a little bit smaller than the sun, and it keeps its planets close: The closest planet orbits every 2 1/2 days, and the fifth planet — the farthest known world from the host star before this sixth was discovered — orbits roughly every 13 days. The sixth orbits every 42 days. (For reference, Mercury, our star's closest planet, orbits the sun every 88 days.)

"Looking at the system architecture now, this planet is much further out; however, it's still consistent with the other planets," Hardegree-Ullman said — all six are between the sizes of Earth and Neptune, a planet size not found in our solar system.

"The difference is you'll see that there are nice spacings, and those spacings get a little bit increasing for each orbit, but then there's this whopping further-out planet," he added. "The question is, could there be more planets in the gap that are either too small to be able to detect with our current technology or could they be just off the plane of orbiting in front of the star? There could be more planets; we need to use other methods to potentially tease that out."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers visualized the planetary system's formation and added audio by converting the planets' orbital frequencies to a human hearing range. So, for instance, the 3:2 resonance between two planets becomes a perfect fifth separation between two notes (like the first two notes of the "Star Wars" theme). The outermost planet is closer to an octave plus something between a perfect fifth and perfect sixth away from its nearest neighbor, according to the science-art outreach program System Sounds.

The visualization, created by astro-musician Matt Russo and colleagues, shows how the planetary-formation disks might have been better-tuned at first but the planets — especially the farthest-out one — wandered slightly off key as the planets reached their final forms and orbits.

"This system was initially tuned while the planets migrated slowly through their birth disk," the System Sounds page reads. "Since the disk disappeared, their orbits have been changing slightly, and they are now in desperate need of a tuneup!"

Going forward, Hardegree-Ullman said, the researchers will try to learn more about the planets' masses and densities. The scientists will also scope out whether there are other planets hidden either in the gap between the fifth and sixth or farther out in the system, he said.

Plus, the system offers an intriguing window into how planetary systems grow and evolve, Caltech astrophysicist Jessie Christiansen, who's also involved with the research, said in a blog post. "Having tightly packed systems that are near resonance, like K2-138, provides a fantastic test bed for examining all sorts of planet and migration theories," she said, "so we are excited to see what will come from this amazing system discovered by citizen scientists on Zooniverse in years to come!"

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.