Weird Star System's Planet-Forming Disk Goes Vertical Like a Ferris Wheel

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Planet-forming disks of material typically orbit around the equators of stars, but now scientists have discovered such rings can go dramatically awry and encircle the poles of stars instead.

The new study suggests that worlds could exist with polar orbits around pairs of stars, potentially leading to seasons extraordinarily different than Earth's.

Stars are born within clouds of gas and dust. The gravitational pull of each star draws such material into spiraling orbits around it. Although clumps of this cloud start off moving in random directions at random speeds, as the cloud collapses, the clumps collide and merge. The result over time is a flattened disk called a protoplanetary disk that usually spins in the same direction as its star and surrounds the star's equator. The planets that emerge from such a disk also typically orbit around the star's equator, as is the case with the worlds of our solar system. [Secrets of Planet Birth Revealed in Amazing ALMA Radio Telescope Images]

Prior work found that nearly all young stars are initially surrounded by protoplanetary disks. In the case of protoplanetary disks around single stars, at least a third go on to form planets, said lead study author Grant Kennedy, an astronomer at the University of Warwick in England.

However, computer simulations have previously suggested that after protoplanetary disks have formed, any extra material they collect can knock them off-kilter. This could explain why astronomers have detected exoplanets with relatively crooked orbits around stars.

Kennedy and his colleagues focused on so-called circumbinary planets, which orbit around binary stars. Scientists had suspected that planets around binary stars could become misaligned — instead of orbiting the stars in the same plane in which the stars orbit one another, these worlds could orbit around their poles instead.

Now, Kennedy and his colleagues have detected the first example of a misaligned circumbinary protoplanetary disk. "It's one of those examples that nature manages to be more creative than we expect," Kennedy told Space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

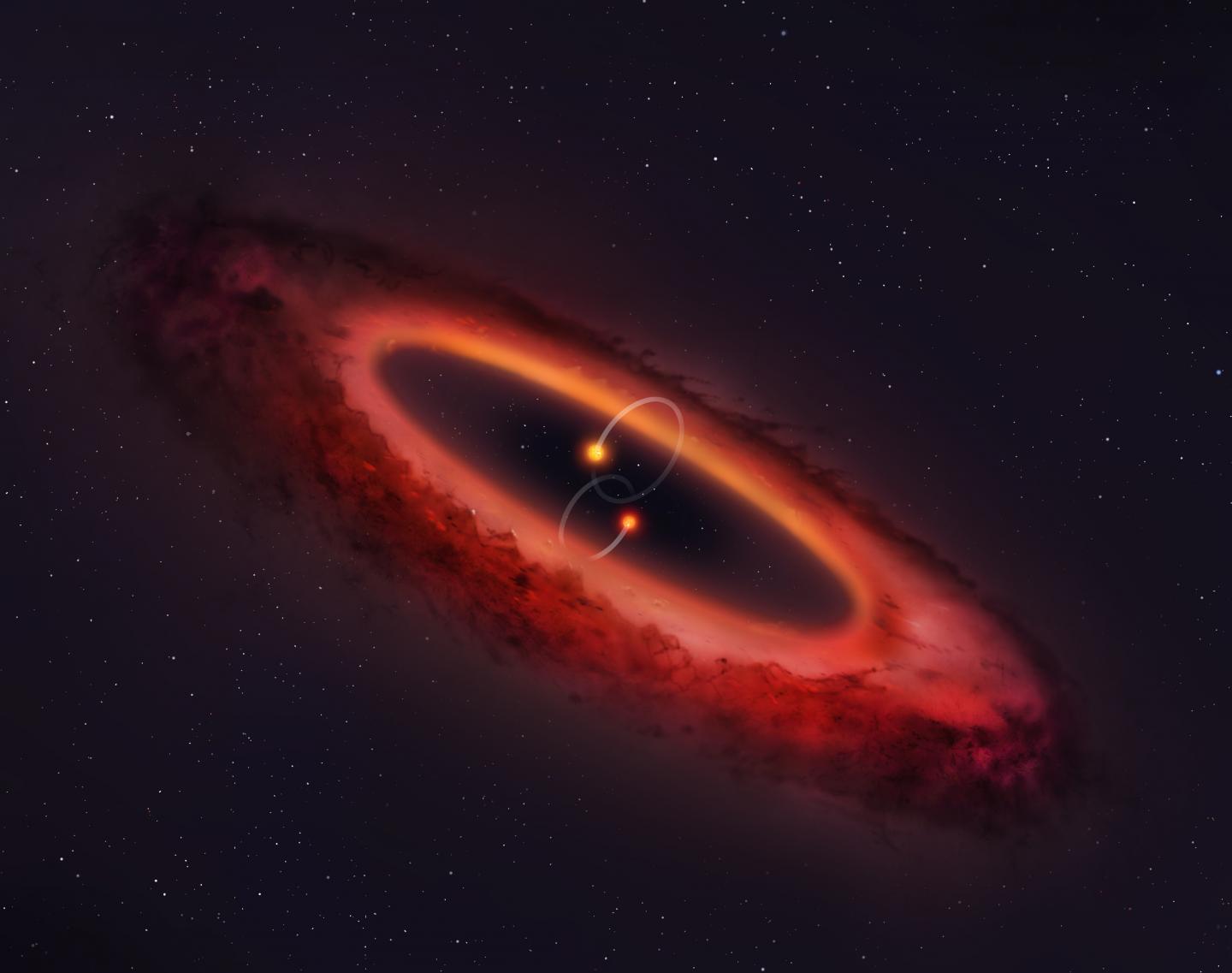

The scientists focused on the quadruple-star system HD 98800, located about 146 light-years from Earth. "If planets were born here, there would be four suns in the sky," study co-author Daniel Price of Monash University in Australia said in a statement.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a huge radio observatory in Chile, the astronomers captured high-resolution images of the protoplanetary disk around two of the four stars. This ring is about the same diameter as the solar system's asteroid belt. (The other two stars lie outside the disk; the two pairs of stars orbit each other.)

Previous research confirmed the way in which these binary stars orbited one another. The new study revealed the protoplanetary disk around these stars essentially orbited around their poles, like a Ferris wheel with a carousel at its center.

"I wasn't actually expecting these data to reveal a polar configuration," Kennedy said. "Based on previous results, I had made all these predictions of complicated warped structures, but they turned out to be completely wrong. The end result is much simpler and more compelling."

These new findings suggest that circumbinary planets in polar configurations may prove more common than often assumed, Kennedy said. "The disks exist, so why shouldn't the planets?" he said.

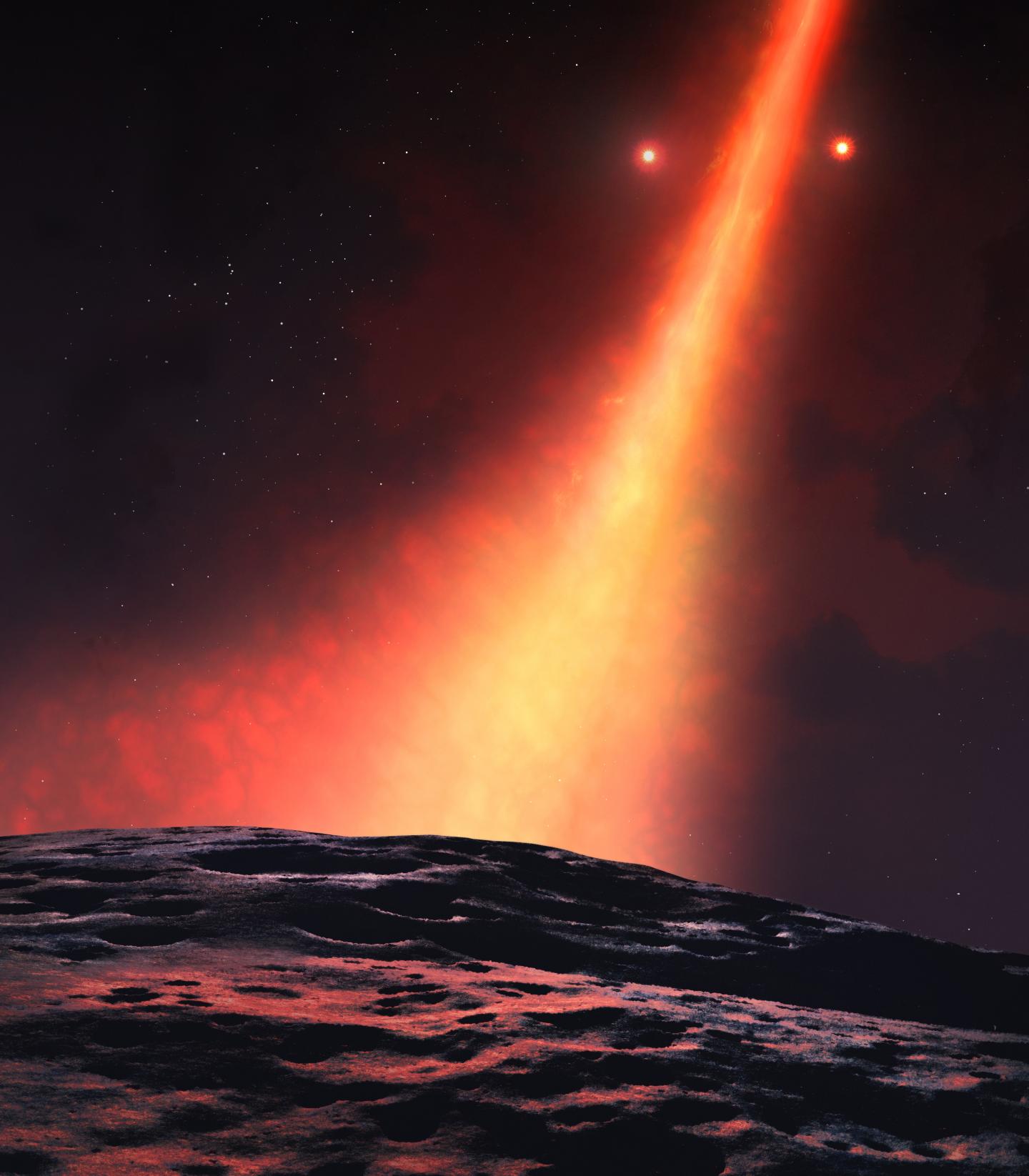

If a planet ever developed from the newfound protoplanetary disk, the scientists noted that from the surface of this world, the disk would resemble a thick band rising almost straight up from the horizon. The pair of stars the planet orbited would appear to move in and out of the plane of the disk, giving items on the world's surfaces two shadows at times. [The Most Fascinating Exoplanets Discovered in 2018]

Such a planet might also experience unusual seasons, Kennedy said. "For Earth, the seasons happen because of the tilt of the Earth's axis," he explained. This leads the amount of daylight each hemisphere gets each day to grow or shrink over the course of the year, and this influences how warm or cold they are, he said.

With any planet that might evolve in HD 98800, axial tilt is not the only potential factor underlying seasonal variations. "The stars will also change their height in the sky as they orbit each other," Kennedy said. Depending on the season, "sometimes there would be two suns during the day, sometimes one."

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Jan. 14) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us