Blood Moon 2019: Why the Coming Lunar Eclipse Spawns Memories of Mr. Magoo

Whenever we have a total eclipse of the moon approaching, as we do now, my mind always drifts back to my very first total lunar eclipse more than half a century ago. And strangely enough, when I think about that magical night, I also reference a famous cartoon character from the past:

Mr. Magoo.

There is a reason for this that I will make clear in just a moment. But first, I should note that as a very young boy my interest in astronomy was only just beginning. In July 1963, I had witnessed a large partial eclipse of the sun from my home in the Bronx. While it was not total, I still remember the excitement of seeing the sun whittled down to a narrow crescent while a strange "counterfeit twilight" fell over the landscape for a minute or two. [Super Blood Moon Lunar Eclipse of 2019: Complete Guide]

Nearly a year and a half later, the newspapers, radio and television were promoting a total eclipse of the moon, which would occur on Friday evening, Dec. 18, 1964. That was an event that I surely wanted to see. The eclipse would start at a very convenient time, 8 p.m. ET, with totality coming just over an hour later. My grandfather would allow me to use his binoculars so that I might get a better look at the subtle shades and colors that would set in during the total phase of the eclipse. As the big night approached, I got more and more enthusiastic.

And then suddenly I became conflicted, thanks to Mr. Magoo.

A viewing quandary

For those who are unfamiliar with Mr. Magoo, he was a cartoon character that was created in 1949 and became very popular during the 1950s and '60s. So popular in fact, that two episodes of Mr. Magoo won Oscars (in 1954 and 1956) in the category of "Best Animated Short Film." The voice of Magoo was supplied by the late Jim Backus, who would go on to play millionaire Thurston Howell III on the TV sitcom "Gilligan's Island."

In 1962, the NBC Network aired "Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol," the very first animated holiday program ever produced specifically for television. I should note here that unlike today, where you have a choice of watching scores of different channels on cable or satellite networks, back then you only had a handful of channels to choose from over the broadcast airwaves. In those halcyon days of the early 1960s, a typical American family might actually build their entire week of television viewing around one particular program (for example, the annual showing of "The Wizard of Oz"), and now this animated rendition of the Charles Dickens' classic also fell into that category. When it debuted in 1962, this portrayal of Ebenezer Scrooge by the popular Mr. Magoo drew a tremendous audience. Magoo was a smash hit in 1962 and 1963, and our family loved it.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But in 1964, just a few nights before the eclipse, NBC announced that it would be airing its annual holiday showing of Mr. Magoo on Dec. 18.

Eclipse night!

At first, I didn't know what to do. I badly wanted to watch both, but I really couldn't be in two places at once! And remember, this was 1964. There were no VCRs to record the program and watch it later. Ultimately, however, I was placated by my mother who pointed out that Magoo would start at 7:30 p.m. but the eclipse would not get underway until 8. So I could watch the first half of the show without any concerns. After 8 o'clock, the moon would begin its track into the Earth's shadow, "but," mom said, "certainly you could run outside during the commercial break to watch the early stages of the moon being covered."

At 8:30, Magoo would be done for another year, and I could fully concentrate on the show in the sky, including totality — two big shows for the price of one! [Amazing Photos of the Rare Supermoon Total Lunar Eclipse]

Hardly bloody

I had read in advance that during a total lunar eclipse the moon is usually transformed into a coppery red ball; indeed, today's society calls it a "blood moon." I looked forward to seeing that firsthand, but ended up a bit disappointed. In 1963, the Mount Agung volcano in Indonesia blew its top and sent a tremendous cloud of ash and dust into the stratosphere, effectively blocking any reddened sunlight normally bent by our atmosphere into Earth's shadow. As a consequence, total lunar eclipses in December 1963 and June 1964 ended up being usually dark — almost black — lacking the ochre/coppery color normally seen during totality.

For "my" eclipse in December 1964, enough of the ash and dust had dissipated to allow for a much brighter eclipse. Still, I saw a lot more of grays and browns as opposed to red. Certainly nothing to suggest the color of blood.

A celestial rerun

I'm really hoping to get a view of our upcoming lunar eclipse Jan. 21 of this year, because in a sense it will mark the return of my "Mr. Magoo Eclipse" of 1964.

It is an interesting phenomenon that an eclipse, whether of the sun or the moon, will repeat itself. Ancient astronomers in Assyria and Babylonia kept track of time by carefully observing the motions of the moon and the sun. By recording the details of solar and lunar eclipses, the accuracy of these measurements increased markedly. As they studied the record of centuries of eclipses, a pattern began to emerge: Eclipses tend to repeat themselves at intervals of just over 18 years, though they recur at different locations on Earth. This eclipse cycle is called the "saros" — Greek for "repetition."

A saros cycle encompasses 18 years and 10 1/3 days or 11 1/3 days, since almost always five or four leap years, respectively, intervene with almost equal frequency. Because of the extra third of a day, each successive eclipse occurs about 120 degrees in longitude to the west of its predecessor.

Thus, after three saros repetitions (54 years and 33+/- 1 days) an eclipse recurs in the same general part of the world. The late science writer Isaac Asimov coined the phrase "triple saros" to describe this interval of time. However, astronomer Owen Gingerich notes that the Greeks called a period equal to three saros cycles an "Exeligmos."

In this case, my 1964 lunar eclipse and our upcoming lunar eclipse are members of saros #134 and can be tied together using the Exeligmos:

Dec. 18, 1964 Mid-totality: 9:37 p.m. EST

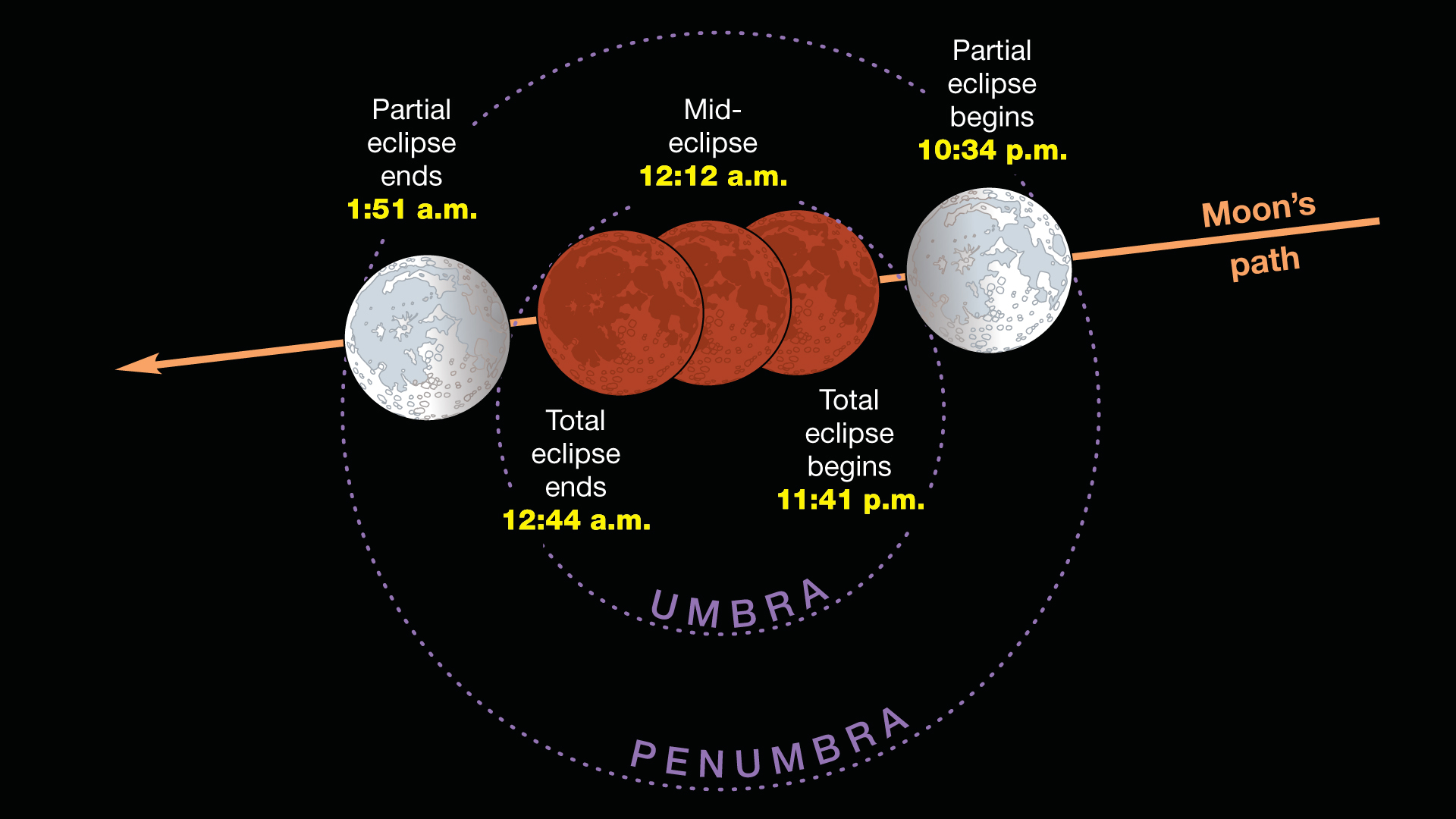

Jan. 21, 2019 Mid-totality: 12:12 a.m. EST

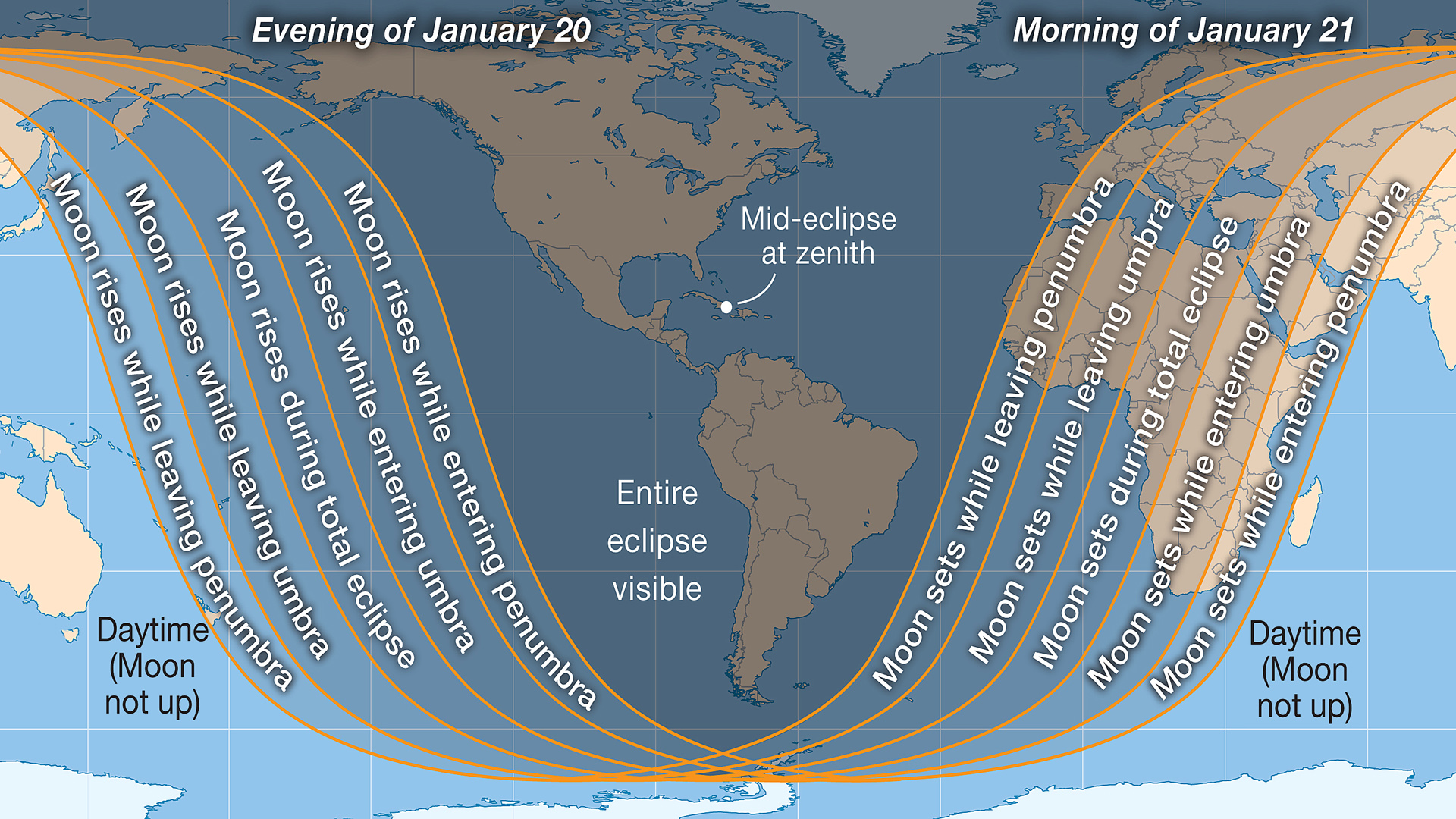

And comparing the path that the moon took through Earth's shadow in December 1964 as well as the general region of the visibility of that eclipse, with the shadow path and visibility zone for our upcoming eclipse, we would readily notice the similarities:

Dec. 18, 1964 diagram from NASA

Jan. 21, 2019 diagram from NASA

Lastly, I should note that at the end of each Mr. Magoo adventure he would use the catchphrase: "Oh, Magoo, you've done it again!"

And we probably can say the same about the Exeligmos.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's Lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.