Watch Ultima Thule Spin Like a Propeller in This Awesome New Horizons Flyby Video

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

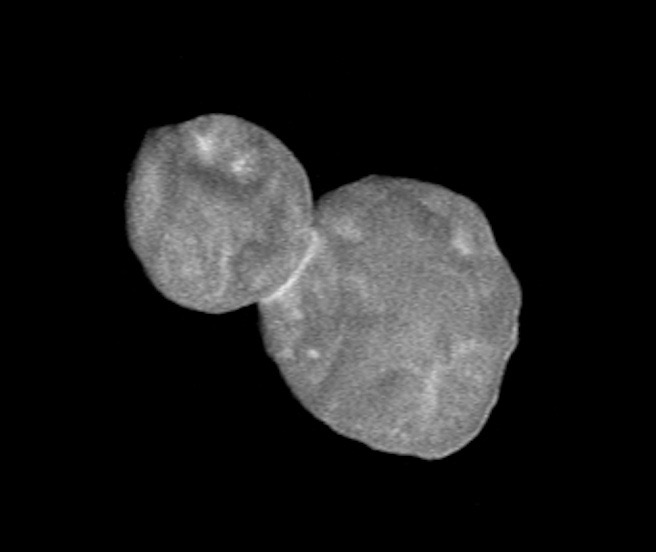

The faraway object Ultima Thule spins into view in a dramatic new video captured by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft.

New Horizons zoomed within just 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) of Ultima Thule in the wee hours of Jan. 1, pulling off the most-distant planetary flyby in spaceflight history. Ultima Thule lies more than 4 billion miles (6.4 billion kilometers) from Earth — 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) beyond the orbit of Pluto, which New Horizons encountered in July 2015.

The video, which mission team members released Tuesday (Jan. 15), captures 7 hours during New Horizons' final approach, just before the probe buzzed the snowman-shaped Ultima Thule. During those 7 hours, New Horizons closed the gap between itself and its target from 310,000 miles (500,000 km) to 17,100 miles (28,000 km), mission team members said. [New Horizons at Ultima Thule: Full Coverage]

And Ultima Thule gets sharper as it looms larger in the frame.

"The original image scale is 1.5 miles (2.5 km) per pixel in the first frame, and 0.08 miles (0.14 km) per pixel in the last frame," New Horizons team members wrote in a description of the new video.

"The rotation period of Ultima Thule is about 16 hours, so the movie covers a little under half a rotation," they added. "Among other things, the New Horizons science team will use these images to help determine the three-dimensional shape of Ultima Thule, in order to better understand its nature and origin."

The brief video also shows why New Horizons didn't detect any brightness variations from Ultima Thule during the approach phase, a surprising development that initially puzzled the mission team. The lack of such a "light curve" is expected for spherical objects, which don't shift from a viewer's perspective as they rotate, but early data indicated that the 21-mile-long (34 km) Ultima Thule was highly elongated.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As we can now see, it was all about New Horizons' orientation to Ultima Thule. The object's pole of rotation was pointing directly at the approaching spacecraft, so New Horizons didn't see any appreciable changes in the light bouncing off Ultima Thule.

We should expect more cool imagery and data from the flyby in the coming weeks. But be patient: Because of low data-relay rates, it'll take about 20 months for all the flyby information to come down to Earth, mission team members have said.

And Ultima Thule may not be New Horizons' last flyby target. The probe is in good enough health, and has enough fuel left, to potentially perform yet another deep-space encounter, if NASA approves another mission extension. (The probe's original mission centered on the Pluto flyby, and the Ultima Thule encounter was the focus of a mission extension that runs through 2021.)

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.