Saturn's Rings May Be Younger Than the Dinosaurs

Saturn has not always had rings — the planet's haloes may date only to the age of dinosaurs, or after it, a new study finds.

The age of Saturn's rings has long proven controversial. Some researchers had thought the iconic features formed along with the planet about 4.5 billion years ago from the icy rubble left in orbit around it after the formation of the solar system. Others suggested the rings are very young, perhaps originating after Saturn's gravitational pull tore apart a comet or an icy moon.

One way to solve this mystery is to weigh Saturn's rings. The rings were initially made of bright ice, but over time have become contaminated and darkened by debris from the outer reaches of the solar system. A few years back, NASA's Saturn-orbiting Cassini mission determined that the rings are only about 1 percent impure. If scientists could weigh Saturn's rings, they could estimate the amount of time it would take for them to accumulate enough contaminants to get 1 percent impure and thus calculate their age, lead study author Luciano Iess, a planetary scientist at the Sapienza University of Rome, told Space.com. [Saturn's Glorious Rings in Pictures]

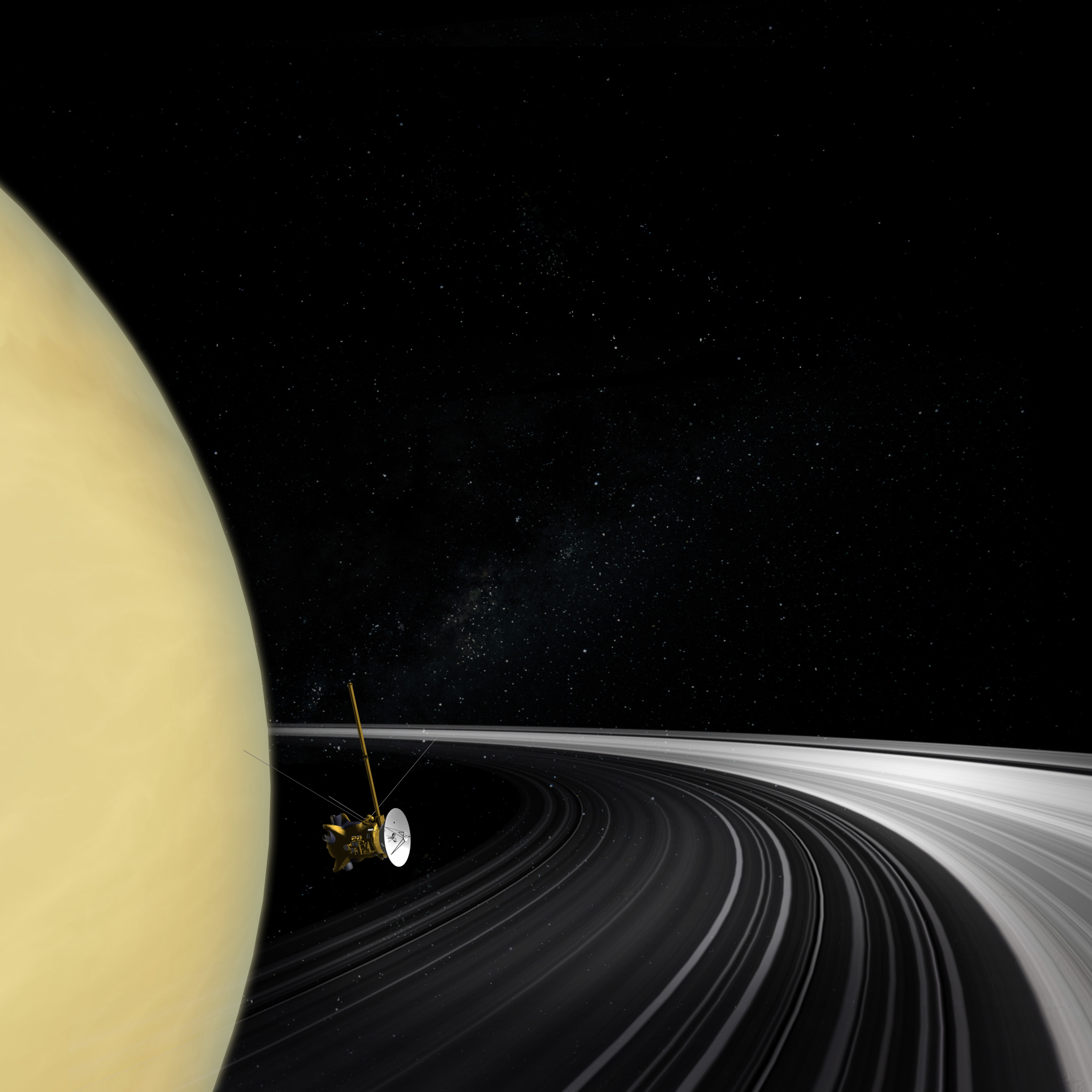

Iess and his colleagues relied on more Cassini data. Before the spacecraft plunged to its death into Saturn's atmosphere in September 2017, it coasted between the planet and its rings and let their gravitational pulls tug it around. The strength of a body's gravity depends on its mass, and by analyzing how much Cassini was pulled one way or the other during the "grand finale" phase of its mission, the mission team could measure the gravity and mass of both Saturn and its rings.

During six of Cassini's crossings between Saturn and its rings at altitudes about 1,615 miles to 2,425 miles (2,600 to 3,900 kilometers) above the planet's clouds, scientists monitored the radio link between the spacecraft and Earth. Much as how an ambulance siren sounds higher pitched as the vehicle drives toward you and lower pitched as it moves away, the radio signals would lengthen in wavelength as their source moved away Earth and shorten as their source moved toward it — an effect called the Doppler shift.

"I'm astonished by the fact that we were able to measure the velocity of a distant spacecraft 1.3 billion kilometers [807 million miles] away from Earth with an accuracy that is a hundredth or a thousandth the speed of a snail — a few hundreds of millimeters per second," Iess said.

Previous estimates based on data from the Voyager flybys of Saturn suggested the rings' mass was about 28 million billion metric tons. The new data from Cassini now suggests the rings' mass is only about 15.4 million billion metric tons. (The largest asteroid, Ceres, has a mass of about 939 million billion metric tons.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

All in all, the researchers suggest the rings formed between 10 million to 100 million years ago. In comparison, the age of dinosaurs ended about 66 million years ago.

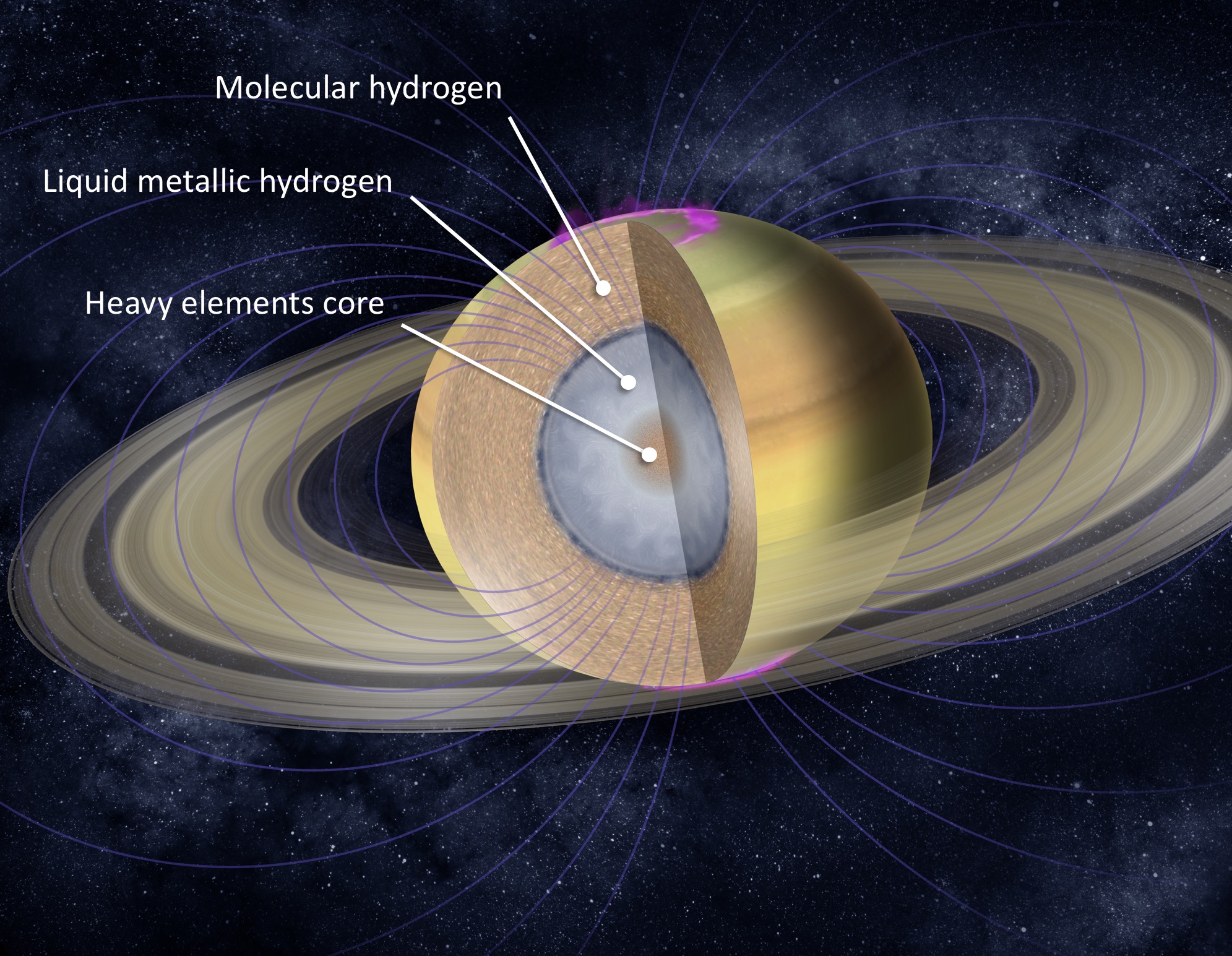

Cassini's grand finale also revealed key details about the internal structure of Saturn. For example, it found that jet streams seen around Saturn's equator — the strongest measured in the solar system, with winds of up to 930 mph (1,500 km/h) — extend to a depth of at least 5,600 miles (9,000 km), rotating a colossal amount of mass around the planet about 4 percent faster than the layer below it.

"The discovery of deeply rotating layers is a surprising revelation about the internal structure of the planet," Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, who did not participate in the study, said in a statement. "The question is, What causes the more rapidly rotating part of the atmosphere to go so deep, and what does that tell us about Saturn's interior?"

The new findings also suggest that Saturn's rocky core is about 15 to 18 times the mass of Earth, similar to prior estimates.

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 17 in the journal Science.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us