How Long Is a Day on Saturn? Scientists Finally Solve a Lingering Mystery

Set your timers for 10 hours, 33 minutes and 38 seconds — scientists have finally figured out how long a day lasts on Saturn, cracking a lingering mystery about the ringed gas giant.

That's according to newly published research that uses data gathered by NASA's Cassini mission before the spacecraft's destruction in September 2017. The new calculation shaves several minutes off previous estimates for a Saturn day, which scientists have been making for decades based on data from the Cassini mission and its predecessor, Voyager.

"The researchers used waves in the rings to peer into Saturn's interior, and out popped this long-sought, fundamental characteristic of the planet. And it's a really solid result," Cassini Project Scientist Linda Spilker said in a statement. "The rings held the answer." [In Photos: Cassini Mission Ends with Epic Dive into Saturn]

It may seem like it should be easy to measure the length of a day on a planet — just wait and watch the world spin. But Saturn's precise day length has stumped scientists for decades. Because the planet is a gas giant, researchers can't watch steady landmarks through the clouds, as they could with a rocky planet.

Scientists can also typically use the tilt of a planet's magnetic field to measure its day length. But that didn't work for Saturn, because the field aligns nearly perfectly with the planet's rotation axis, stymying their calculations. One scientist who has studied the planet's magnetic field said that the day-length uncertainty is "a bit embarrassing," speaking in an interview with Space.com about research published in October.

These challenges left scientists with rough estimates falling between 10 hours, 36 minutes and 10 hours, 48 minutes — not particularly satisfying.

The research published today took an entirely different approach — looking not to the planet itself, but at its delicate rings. This idea was proposed in 1982, but not until the Cassini mission did scientists have the data to see if the technique would work.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

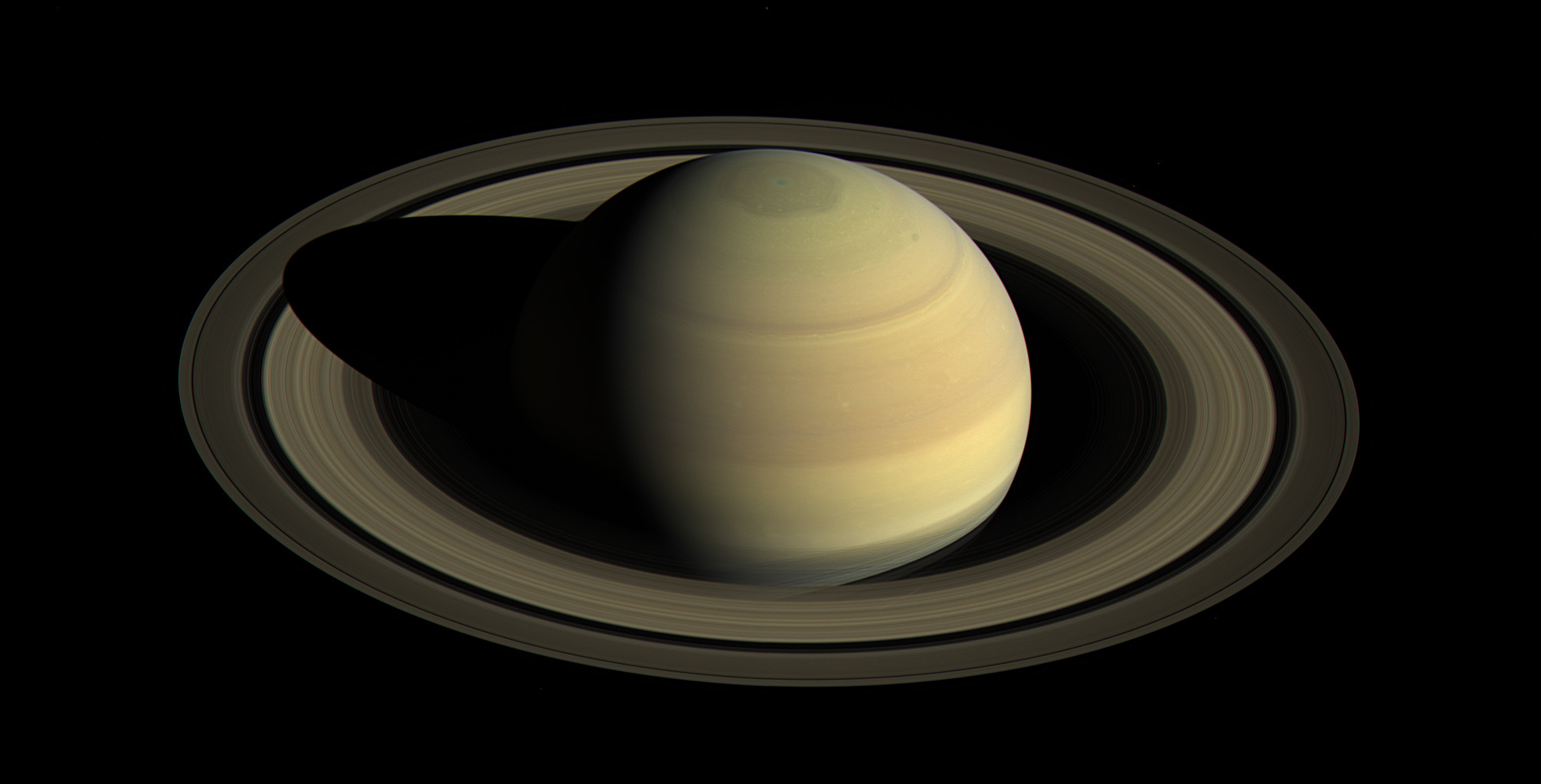

The idea is that as Saturn spins, its insides wiggle a little, causing small changes in the planet's gravitational field. Those small changes ripple out to the chunks of ice in the rings that decorate the gas giant, causing small waves in the rings.

"Particles throughout the rings can't help but feel these oscillations in the gravity field," lead author Christopher Mankovich, a graduate student in astronomy at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said in a statement. "At specific locations in the rings, these oscillations catch ring particles at just the right time in their orbits to gradually build up energy, and that energy gets carried away as an observable wave."

So, Mankovich and his colleagues studied those observable waves and used them to backtrack inward to the planet itself. That's how the researchers came up with the measurement of 10 hours, 33 minutes and 38 seconds. It's still not set in stone — the error bars on that calculation stretch between a minute and 52 seconds longer and a minute and 19 seconds shorter. But the new calculation's range beats a 12-minute window.

The research is described in a paper published yesterday (Jan. 17) in The Astrophysical Journal.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.