The long-ago giant impact that led to the formation of Earth's moon also helped make life as we know it possible on our planet, a new study suggests.

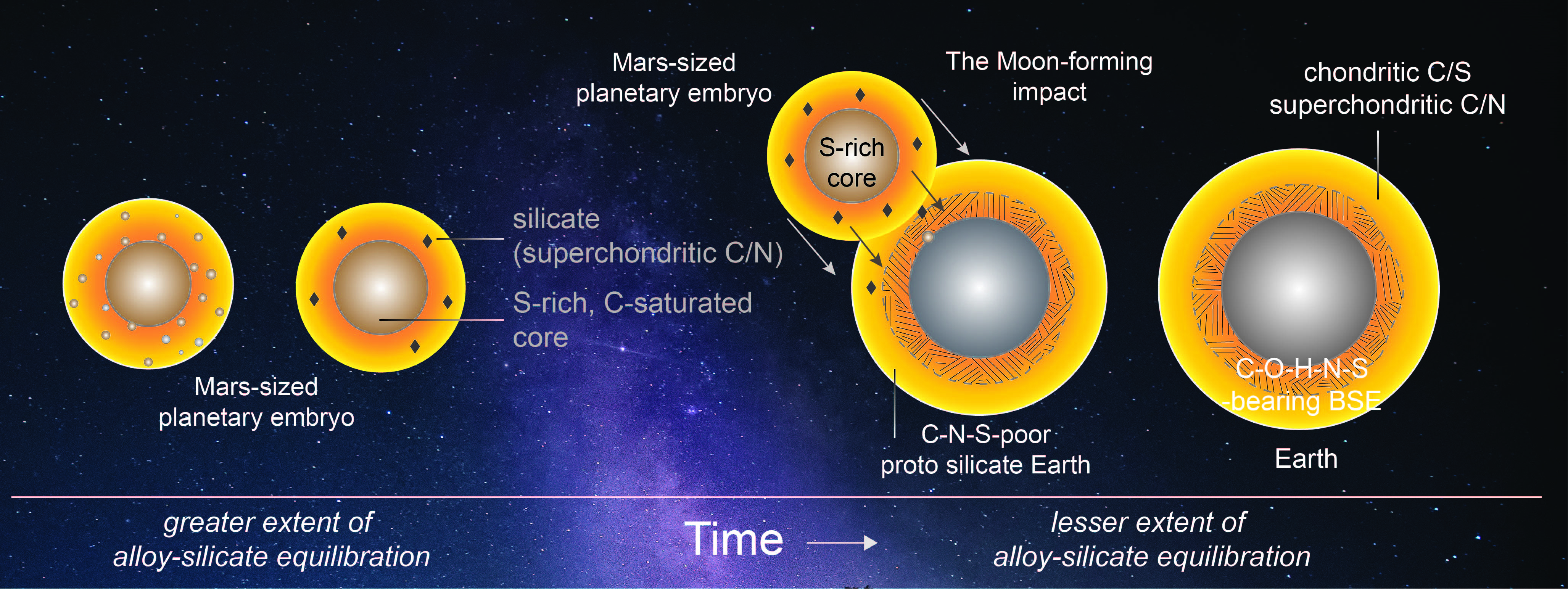

More than 4.4 billion years ago, scientists believe, a Mars-size planet dubbed Theia slammed into the proto-Earth, blasting huge amounts of material from the pair into space. Some of this violently liberated stuff eventually coalesced to form the moon, while other bits and pieces were gobbled up by our bashed and bleeding world.

Some of this newly incorporated material turned out to be pretty important. According to the study, the catastrophic collision provided Earth with most of its carbon, nitrogen and sulfur, key chemical building blocks of life as we know it. [How the Moon Evolved: A Photo Timeline]

"This study suggests that a rocky, Earth-like planet gets more chances to acquire life-essential elements if it forms and grows from giant impacts with planets that have sampled different building blocks, perhaps from different parts of a protoplanetary disk," co-author Rajdeep Dasgupta, a professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Rice University in Houston, said in a statement.

Carbon, nitrogen and sulfur are "volatile" elements, meaning they have a relatively low boiling point and can be tough for nascent planets and moons to hang onto. A number of other life-important chemicals, including water, are volatiles as well.

"From the study of primitive meteorites, scientists have long known that Earth and other rocky planets in the inner solar system are volatile-depleted," Dasgupta said. "But the timing and mechanism of volatile delivery has been hotly debated. Ours is the first scenario that can explain the timing and delivery in a way that is consistent with all of the geochemical evidence."

The researchers, led by Rice graduate student Damanveer Grewal, performed laboratory experiments at high temperatures and pressures, mimicking the conditions present during planetary-core formation. They looked at how much carbon and nitrogen got incorporated into the simulated core at sulfur concentrations of 0, 10 and 25 percent, respectively. (Theia may have had a sulfur-rich core. And some scientists have posited that sulfur blocks core uptake of carbon and nitrogen, pushing these elements out into the mantle and crust, which together are known as the "bulk silicate Earth.")

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team also ran computer simulations, exploring more than 1 billion different scenarios to better understand how Earth got its volatiles.

"What we found is that all the evidence — isotopic signatures, the carbon-nitrogen ratio and the overall amounts of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in the bulk silicate Earth — are consistent with a moon-forming impact involving a volatile-bearing, Mars-sized planet with a sulfur-rich core," Grewal said in the same statement.

The results, which were published online Wednesday (Jan. 23) in the journal Science Advances, could have applications beyond our own planet, helping scientists gain a better general understanding of the conditions necessary for life to arise throughout the cosmos.

"This removes some boundary conditions," Dasgupta said. "It shows that life-essential volatiles can arrive at the surface layers of a planet, even if they were produced on planetary bodies that underwent core formation under very different conditions."

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.