Ant Attack! Insects Swarm Australian Ring-Hunting Telescope

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A swarm of ants attacked a small telescope in Australia earlier this year, and when they died, their tiny corpses blew out the power supply.

The Australian Beta Pictoris b Ring instrument (bRing-AU) was part of a fleet of instruments used last year to hunt for signs of rings or an exomoon around Beta Pictoris, a young star hosting at least one planet. While the hunt was unsuccessful, astronomers are continuing to monitor the star, along with tens of thousands of other stellar targets in the southern sky to obtain additional science.

The ants didn't make waves climbing on the exterior of the instrument. According to Samuel Mellon, a doctoral candidate at the University of Rochester who is working with bRing, the telescope sits on a few bricks to elevate it off the ground, with an aluminum sheet attached to serve as a floor. That may have provided the point of entry for the insects. [Alien Comets of Star Beta Pictoris Explained (Infographic)]

"A minor imperfection in the seal between this and the frame could have allowed them to get in," Mellon told Space.com. Another possibility is that the small black ants, only a few millimeters in length, climbed in through the external fans, but he said this was unlikely as a very fine grill covers each of the fans. He was not certain what species the ants were.

"We anticipated a possible insect invasion and did our best to seal bRing on all sides and edges with sealant and weatherproof tape," Mellon said. "However, ordinary wear and tear could have opened a vulnerability for the tiny ants to get in."

Invasive insects

Located 63.4 light-years from the sun, Beta Pictoris is roughly 20million years old. Disks of dust and gas around the star have long suggested the presence of planets. In 2008, astronomers captured an image of a new planet, Beta Pictoris b. The planet appears to be between 9 and 13 times the mass of Jupiter, and it orbits about nine times farther from its star than Earth over the course of 20 years. Astronomers think the baby star may also host a swarm of comets.

In 2016, astronomers calculated that, while the planet would not pass directly between its star and Earth, the region around the star where rings or moons could be held gravitationally would. They began a seven-month campaign to study the star, setting up instruments in places such as South Africa and Antarctica, and even launching a small telescope into space.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One of these instruments was bRing, twin telescopes placed in Australia and South Africa. Housed at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales, Australia, bRing-AU used two wide-field cameras to probe the light coming from the star. Just as a planet passing between its star and Earth causes a slight decrease in the star's brightness, astronomers hoped that any rings or moons around the planet that passed the star could cause a similar dip.

The suite of instruments studied Beta Pictoris intently from April 2017 to January 2018, but neither moons nor rings appeared. That doesn't dissuade Paul Kalas, an astronomer at Berkeley who helped bring together the international teams that worked together to search for the rings. Kalas told Space.com that it's possible that the planet could still host natural satellites but the geometry wasn't lined up to make them visible from Earth.

"You can still have a ring system," Kalas said.

After the hunt drew to a close, bRing-AU has continued to observe tens of thousands of stars, including Beta Pictoris. But that project was briefly halted at the dawn of the year thanks to some insect interference.

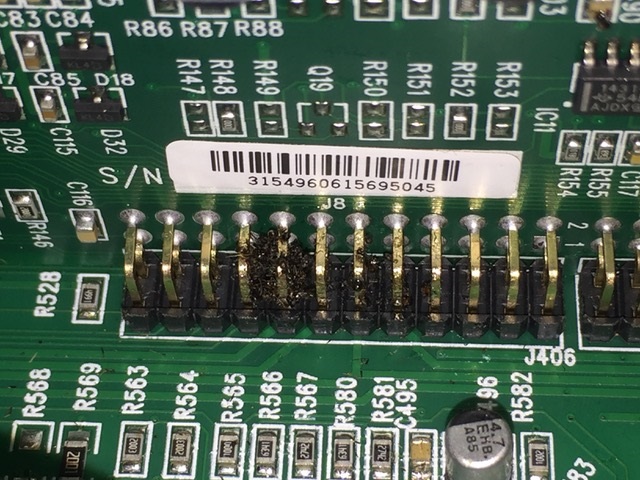

"We noticed a power failure in early January 2019," Mellon said. "The handy staff at Siding Spring observatory opened up the power supply and found that the ants had shorted it out."

About a hundred ants had swarmed into the tiny telescope. Mellon isn't sure what drew the first insect investigators, but he speculated that the cause could have been electromagnetic, since they were attracted only to the power supply.

"They could also have been looking for shelter and wandered into the wrong area," he said.

On their death, the ants seemed to release a pheromone that attracted other ants to attack, causing a swarm. The process is similar to how a species known as "crazy ants," a species from South America that has invaded the Gulf Coast,short out electronics.

"When a few were electrocuted, the rest must have been summoned," Mellon said.

The pileup of corpses eventually fried the power supply, leading the Siding Spring staff to investigate. They cleaned out the dead ants and installed ant traps and repellents to keep away other curious creatures.

"We have replaced the power supply and set up ant traps and repellents and better sealed the instrument," Mellon said. "bRing-AU is back up to taking data."

The brief power supply loss came after the observations of the Beta Pictoris transit had been completed, so the ants did not interrupt the hunt for the exorings. The ants did, however, put a brief stop to the next stage of observations while the power supply was replaced. No other part of the instrument was damaged, and none of the staff was bitten.

Although the team tried to anticipate potential problems, Mellon said he would have taken further steps if he had realized how determined the insects would be.

"Had I known my instrument would have been invaded by ants, I would have installed ant traps," he said. However, "this situation would have been hard to predict for anyone."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky