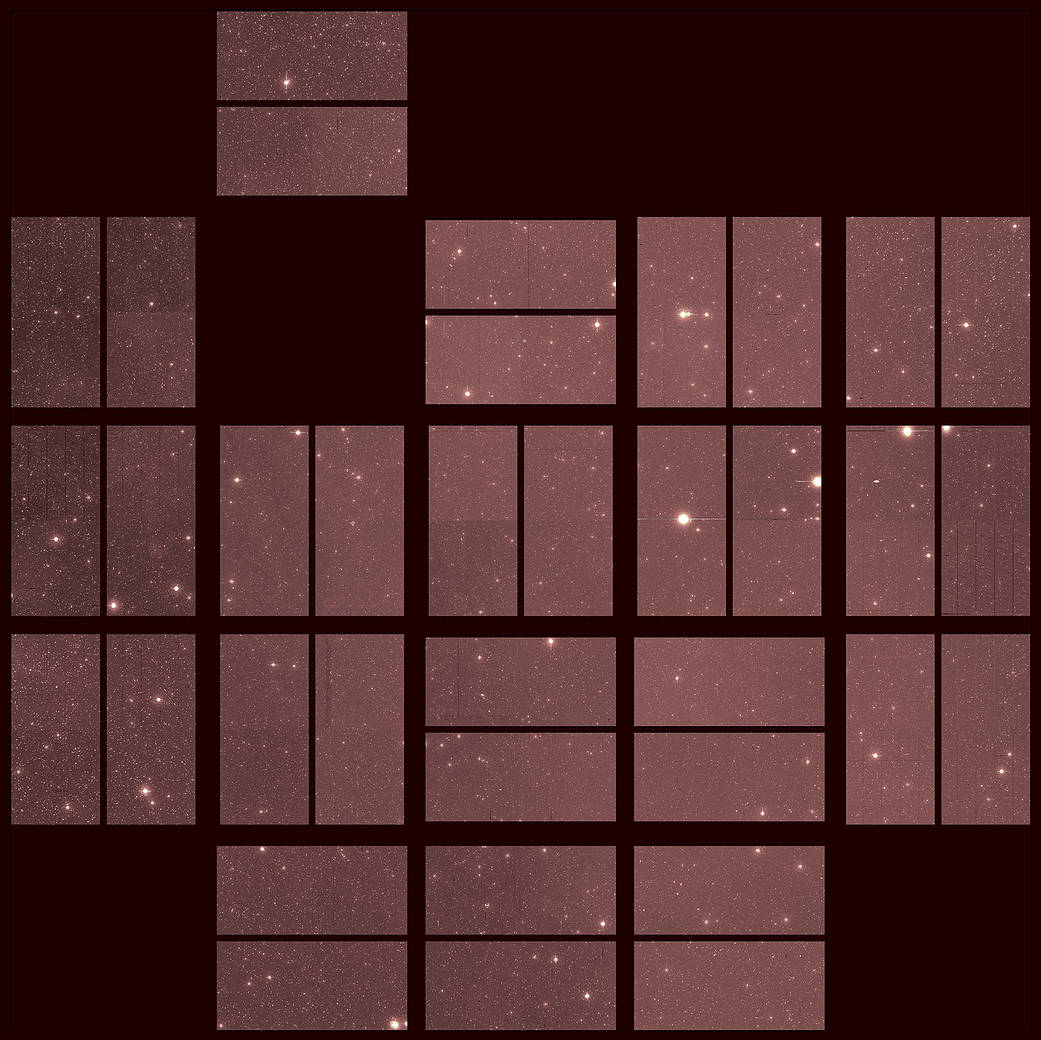

Last Light: Here's the Final View from NASA's Planet-Hunting Kepler Space Telescope

The Kepler Space Telescope found thousands of planets around other stars by documenting their telltale flickers before it ran out of fuel last fall — and a newly released image shows the spacecraft's full field of view for the last time.

Telescopes will often release a "first light" image — or, in the case of space telescopes, send one back to Earth — documenting its first scientific view of the cosmos. Kepler's first light came in April 2009, after it jettisoned the protective dust shield over its sensitive camera. Its parallel "last light" image, it's final full scan of the skies, came back Sept. 25, 2018, according to a statement from NASA.

Kepler orbits the sun on a path trailing Earth. The spacecraft's first mission, which stretched from 2009 to 2013, had it staring fixedly at a narrow patch of sky in the constellation Cygnus. After two of Kepler's four reaction wheels failed, it was no longer able to precisely stay pointed at one spot — so the scientists proposed a K2 mission that saw it staring at different spots for about 75 days each. During both missions, the telescope pinpointed more than 2,600 confirmed exoplanets (and many more that have not been confirmed yet using other data). [7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets]

Because of this switch in mission, its last-light view doesn't match up with its first-light image — but it gave the spacecraft a chance to hunt alien worlds across different parts of the sky. Its final field of view, in the constellation Aquarius, includes the TRAPPIST-1 system that hosts seven rocky planets, according to NASA.

Kepler's fixed eye spotted exoplanets by noticing patterns of dimming in stars as their planets passed in front of them — a strategy called the transit method. While it will no longer return information, planet hunters are still finding traces of new planets in its data, and even more can be confirmed by comparing with other telescopes whose fields overlap, such as the newly launched TESS spacecraft.

Besides its full field of view, Kepler took photos of certain targets at 30-minute intervals. It returned those images for several hours after its final image of the full star field, NASA officials said in the statement. A few of those views are included throughout this article — the stars' movement comes from Kepler's decreasing thruster performance.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.