Our Milky Way galaxy will survive in its current form a bit longer than some astronomers had thought, a new study suggests.

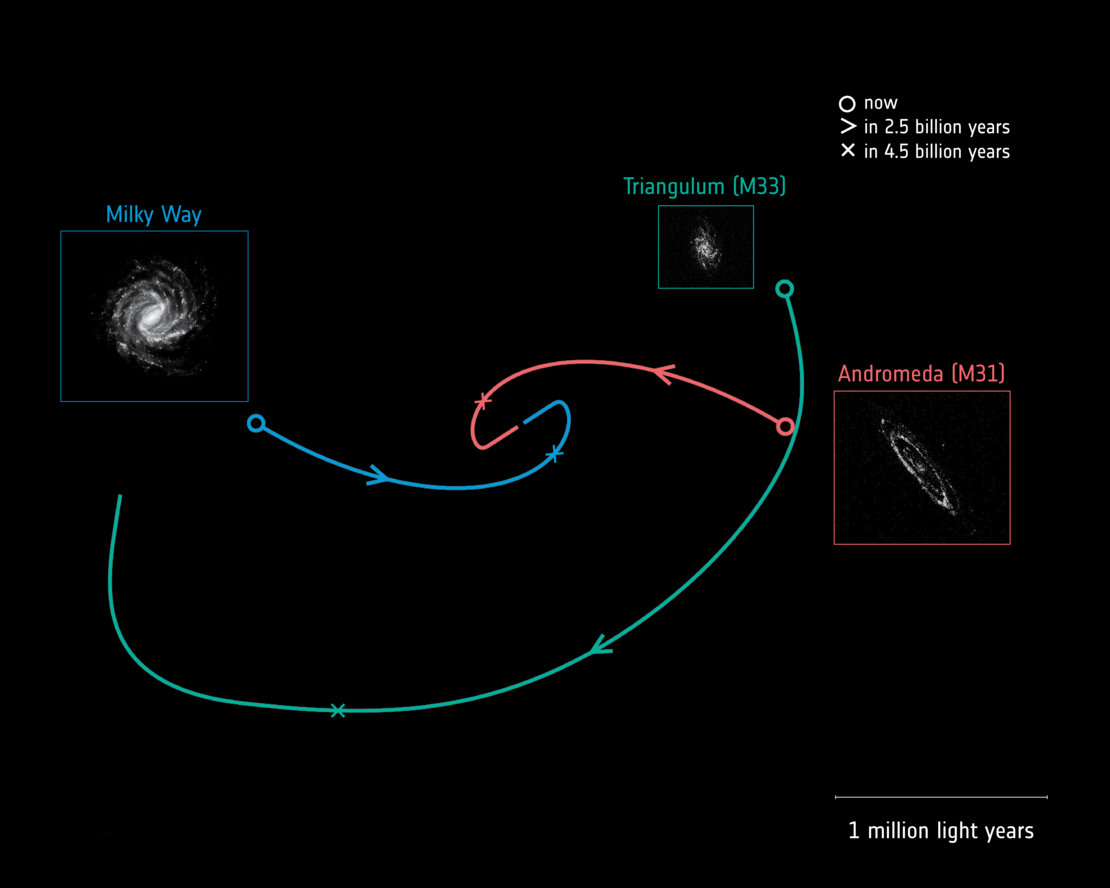

The monster collision between our Milky Way and fellow spiral galaxy Andromeda will occur about 4.5 billion years from now, according to the new research, which is based on observations made by Europe's Gaia spacecraft. Some prominent previous estimates had predicted the crash would happen significantly sooner, in about 3.9 billion years.

"This finding is crucial to our understanding of how galaxies evolve and interact," Gaia project scientist Timo Prusti, who was not involved in the study, said in a statement. [Images: Milky Way Galaxy's Crash with Andromeda]

Gaia launched in December of 2013 to help researchers create the best 3D map of the Milky Way ever constructed. The spacecraft has been precisely monitoring the positions and movements of huge numbers of stars and other cosmic objects; the mission team aims to track more than 1 billion stars by the time Gaia shuts its sharp eyes for good.

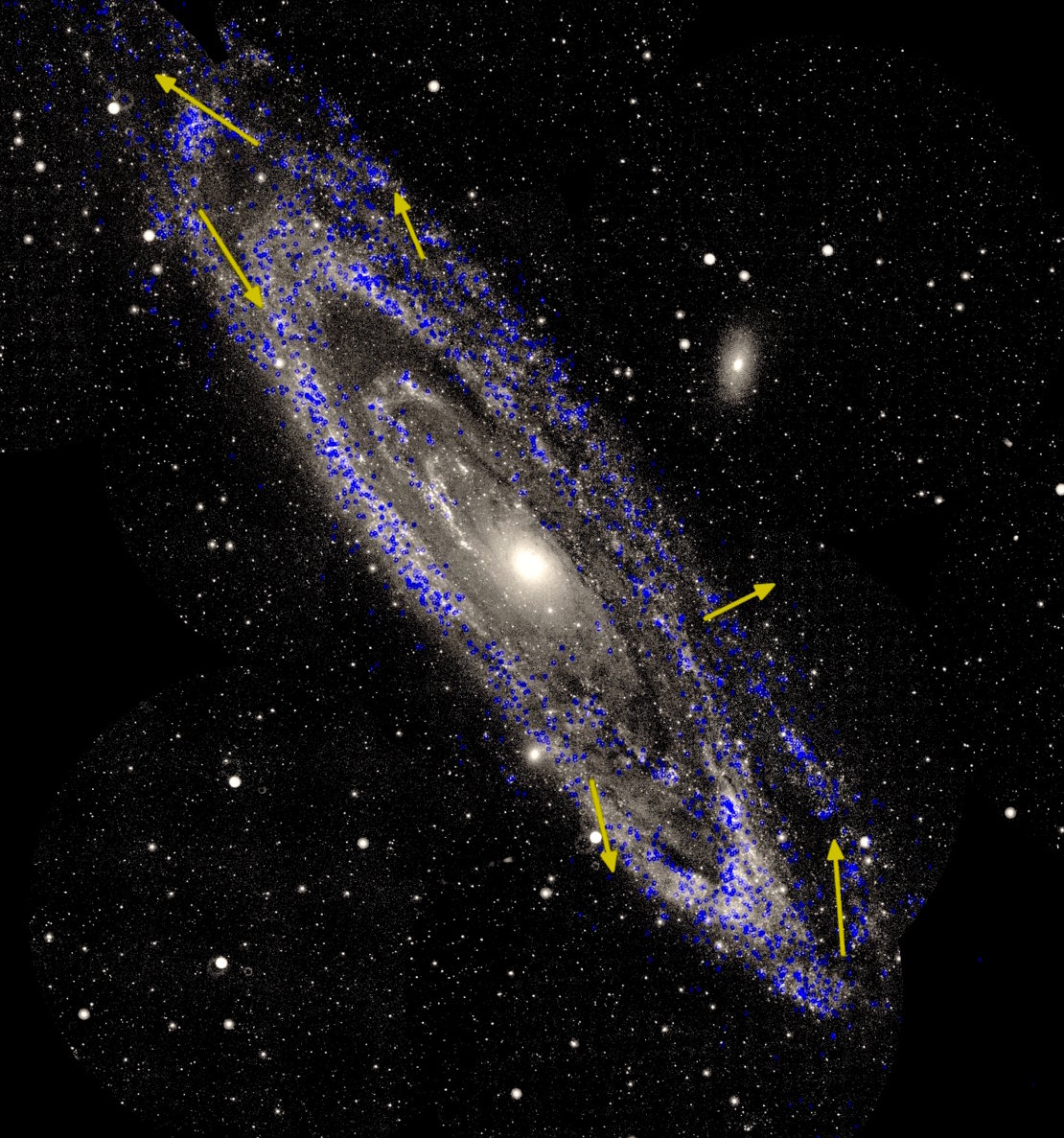

Most of the stars Gaia is eyeing are in the Milky Way, but some are in nearby galaxies. In the new study, the researchers tracked a number of stars in our galaxy, in Andromeda (also known as M31) and in the spiral Triangulum (or M33). These neighbor galaxies are within 2.5 million to 3 million light-years of the Milky Way and may be interacting with each other, study team members said.

"We needed to explore the galaxies' motions in 3D to uncover how they have grown and evolved and what creates and influences their features and behavior," lead author Roeland van der Marel, of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said in the same statement.

"We were able to do this using the second package of high-quality data released by Gaia," van der Marel added, referring to a haul released in April 2018.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This work allowed the team to determine the rotation rates of both M31 and M33 — something that had never been done before, the researchers said. Using the Gaia-derived findings and analyses of archival information, the study team mapped out how M31 and M33 have moved through space in the past and where they'll likely go over the next few billion years.

The team's models give a later-than-expected date for the Andromeda-Milky Way smashup and also suggest that it will be more of a sideswipe than a head-on collision. (Because the distances between stars are so great, the odds that our own solar system will be disrupted by the merger are very low. But the crash will definitely liven up the night sky for any creatures that are around on Earth 4.5 billion years from now.)

"Gaia was designed primarily for mapping stars within the Milky Way — but this new study shows that the satellite is exceeding expectations and can provide unique insights into the structure and dynamics of galaxies beyond the realm of our own," Prusti said. "The longer [that] Gaia watches the tiny movements of these galaxies across the sky, the more precise our measurements will become."

The new study was published this month in The Astrophysical Journal.

By the way, Andromeda won't be the next galaxy our Milky Way slams into: The Large Magellanic Cloud and Milky Way will merge about 2.5 billion years from now, a recent study suggested.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.