Ultima Thule Beyond Pluto Is Flat Like a Pancake (and Not a Space Snowman After All)

Ultima Thule doesn't look much like a snowman after all.

The final photos that NASA's New Horizons spacecraft snapped of Ultima Thule during the probe's epic Jan. 1 flyby reveal the distant object to be far flatter than scientists had thought, mission team members announced today (Feb. 8).

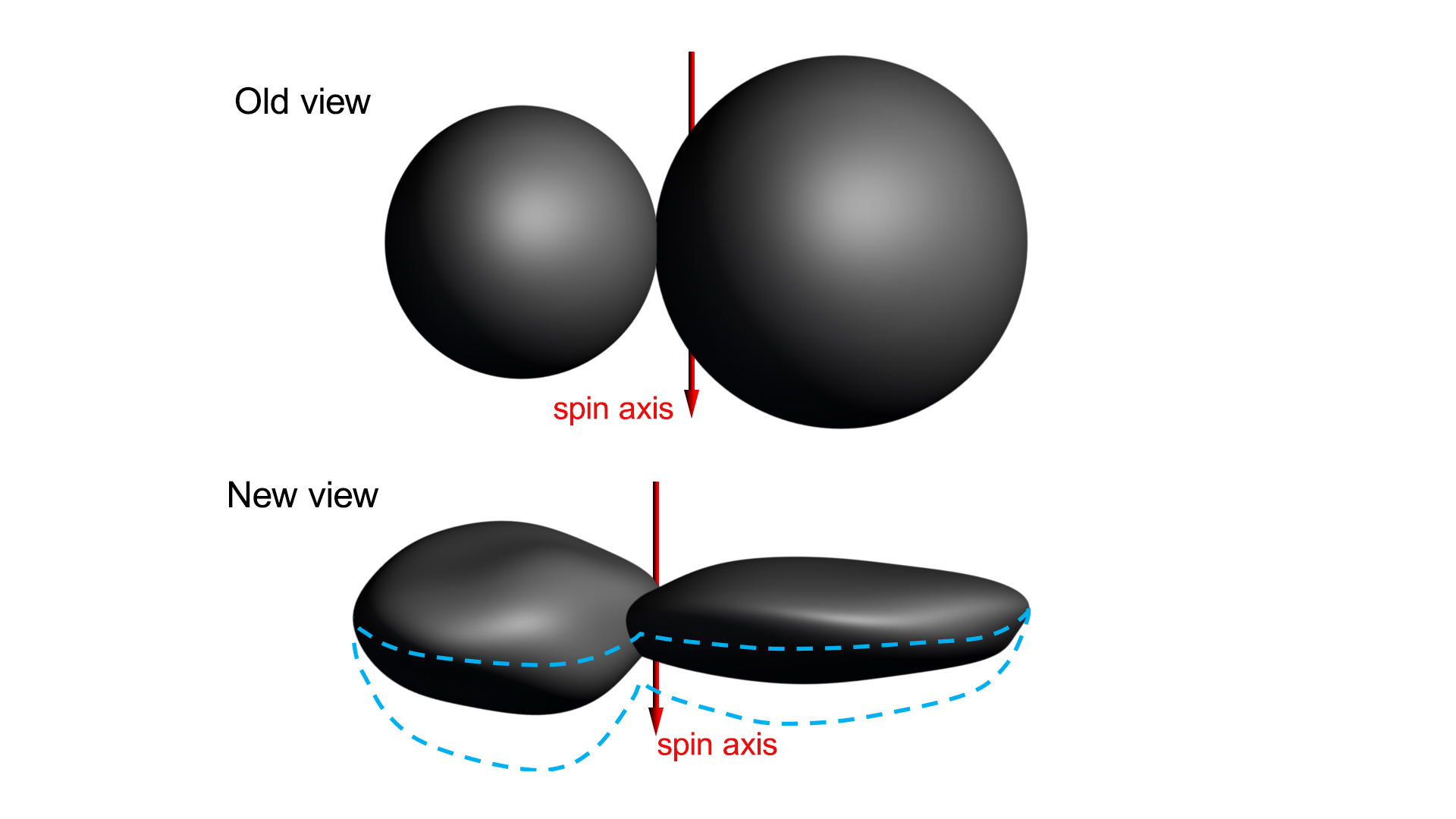

"We had an impression of Ultima Thule based on the limited number of images returned in the days around the flyby, but seeing more data has significantly changed our view," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement. [New Horizons at Ultima Thule: Full Coverage]

"It would be closer to reality to say Ultima Thule's shape is flatter, like a pancake," Stern added. "But more importantly, the new images are creating scientific puzzles about how such an object could even be formed. We've never seen something like this orbiting the sun."

The $720 million New Horizons mission launched in January 2006 to perform the first-ever flyby of Pluto. The probe aced this encounter in July 2015, revealing the dwarf planet to be a spectacularly diverse world of surprisingly varied and rugged landscapes.

New Horizons then set out an extended mission, which centered on a close flyby of Ultima Thule, which is officially known as 2014 MU69. This object is about 21 miles (34 kilometers) long and lies 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) beyond Pluto's orbit. (Ultima is currently 4.1 billion miles, or 6.6 billion km, from Earth.)

Initial imagery taken during New Horizons' approach suggested that Ultima Thule is shaped like a bowling pin. But that impression changed shortly before closest approach, which occurred just after midnight on New Year's Day and brought the probe within 2,200 miles (3,540 km) of the mysterious body. Photos snapped around that time indicated that Ultima Thule is composed of two lobes, both of which appeared to be roughly spherical.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A snowman, with a distinctly reddish hue.

But the newly released images have forced another rethink. New Horizons took the long-exposure photos about 10 minutes after closest approach; the central frame in the sequence was snapped from a distance of 5,494 miles (8,862 km), mission team members said.

The new views were captured from a different angle than the snowman-suggesting photos, and they show Ultima Thule's outline against a number of background stars. By noting which of these stars went dark as Ultima blocked them out, mission scientists were able to map out the object's (surprisingly flat) shape.

"This really is an incredible image sequence, taken by a spacecraft exploring a small world 4 billion miles away from Earth," Stern said. "Nothing quite like this has ever been captured in imagery."

While the newly released images are the final ones New Horizons snapped of Ultima, they're far from the last pieces of data we'll see from the probe. It'll take a total of about 20 months for New Horizons to send home all of its flyby imagery and measurements, mission team members have said.

And Ultima Thule may not be the spacecraft's final flyby target. New Horizons is in good health and has enough fuel to zoom by another distant body, if NASA grants another mission extension, Stern has said. (The current extended mission runs through 2021.)

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.