Why (and How) to Skywatch When Winter Temperatures Plummet

One of the big news stories nationally over the past few weeks has been the invasion of the polar vortex in the northern tier of the United States. It swept a brutally frigid surge of air in from the polar regions. This, in turn, dropped temperatures to record or near-record levels from the Plains states through the Midwest and on into New England.

For stargazers, cold winter nights (including before the vortex) made for some tough decisions. Recall that there was a spectacular total eclipse of the moon on the night of Jan. 20. Many locations were blessed with clear skies, but because of potentially dangerous windchills, some space fans passed on watching this great show.

And just last week, the moon, having shrunk to a narrow crescent, interacted with three bright planets (Venus, Jupiter and Saturn), producing a series of beautiful celestial tableaus on consecutive mornings. But the show was confined to the early morning, when temperatures were at their lowest, in some cases well below 0 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 18 degrees Celsius). So, many people remained in the comfort of their warm beds rather than head outside to enjoy this ever-changing "dance" of the moon and planets. [Amazing Photos of the Super Blood Wolf Moon!]

But bundling up to see the winter sky is well worth the wait. In a moment, I'll offer some suggestions on how to best handle the cold when skygazing. But first, here are some specifics on why cold nights in January and February appear so much clearer compared to those balmy nights in July and August.

Cold equates to crystal clear

We're now at midwinter; in fact, the halfway point of the season came at 5:10 a.m. EST (1010 GMT) this past Monday (Feb. 4). Night skies now seem especially transparent. One reason for the clarity of a winter's night is that cold air cannot hold as much moisture as warm air can. Hence, on many nights in the summer, the warm, moisture-laden atmosphere makes the sky appear hazier. By day, the summer sky is a milky, washed-out blue, which in winter, becomes a richer, deeper and darker shade of blue. For us in northern climes, this only adds more luster to that part of the sky containing the beautiful wintertime constellations.

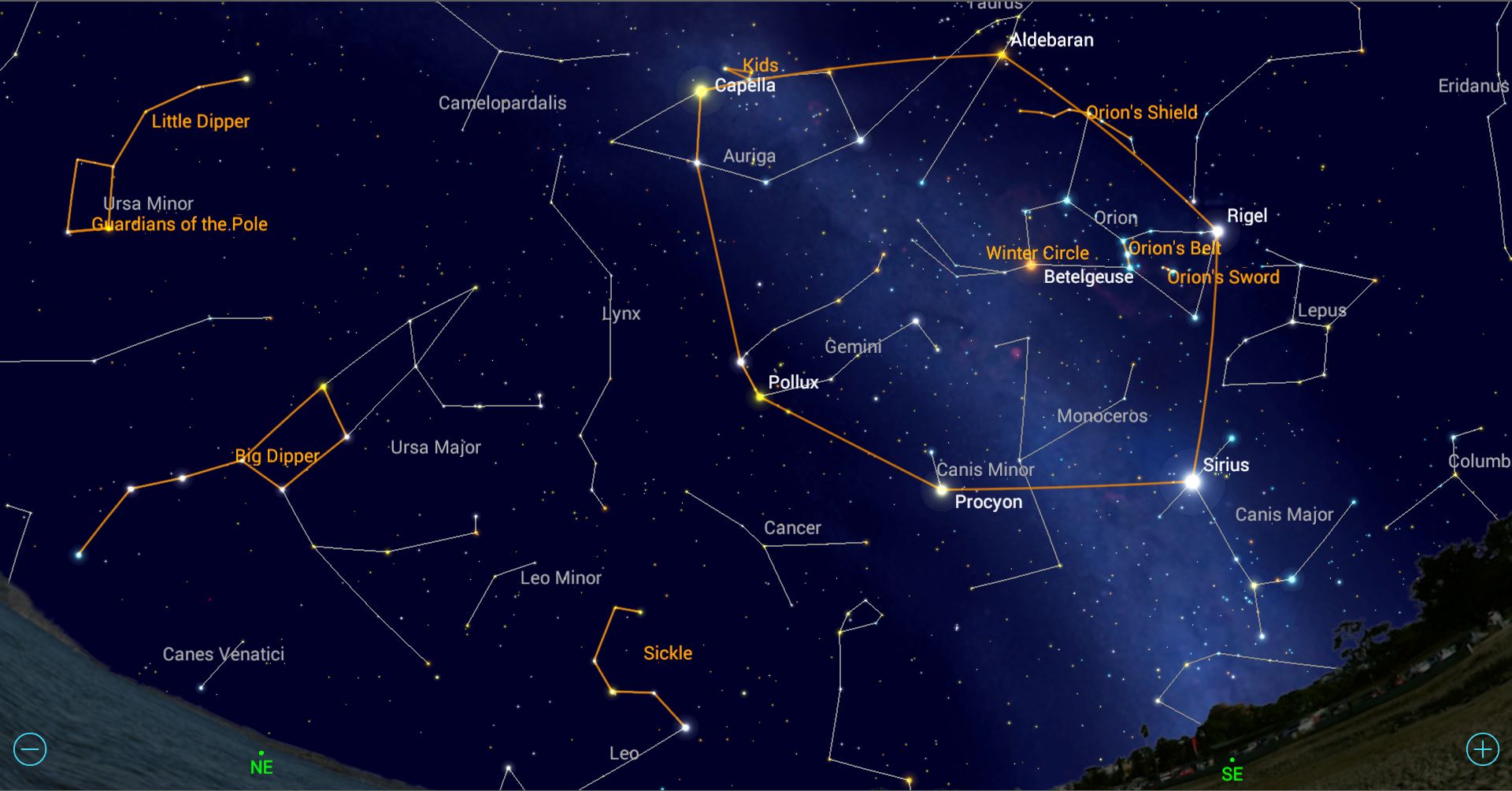

Step outside around 9 p.m. this month, and you'll see Orion, the hunter, along with Taurus, the bull to Orion's upper right. To the hunter's lower left, you'll see his faithful companion, Canis Major, the big dog. A line extended diagonally in either direction through Orion's belt will take you to the brightest star in Taurus, the orange-hued Aldebaran, and the brightest of all stars, bluish-white Sirius.

There are also some beautiful deep-sky objects to gaze at, such the V-shaped Hyades star cluster, which marks the face of Taurus, and the Pleiades cluster, popularly known as "the Seven Sisters." Just below the Belt of Orion is the Great Nebula, a superb sight in telescopes. It's a vast cloud of extremely tenuous glowing gas and dust located approximately 1,600 light-years away from Earth and stretching about 30 light-years across (or more than 20,000 times the diameter of our entire solar system). Astrophysicists now believe that this nebulous stuff is a stellar incubator, the primeval chaos in which star formation is presently occurring.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A recommendation for binoculars

If you have a telescope, especially a large one, a very cold night might make you think twice about bringing the instrument outside. Just trying to properly set it up in such conditions can be problematic. And yet, you can still get a nice view of the sights I just described if you use a pair of good binoculars. No time-consuming setup necessary; just step outside and aim toward your cosmic quarry.

In fact, for manyskywatching situations, binoculars are the best instrument to use. They are lightweight and portable, and quality binoculars can far outrank a poor-quality, small telescope. Also, they should last you a lifetime. Beginners usually are pleasantly surprised the first time they sweep the night sky with binoculars, and advanced amateurs and professionals alike regard the instruments as standard viewing equipment.

Any good pair of 7-power binoculars, when held steadily (or mounted on a tripod), will give you a glimpse of the craters on the moon, the crescent of Venus and the moons of Jupiter. Binoculars are great for star clusters like the Hyades and Pleiades. And by just sweeping along the Milky Way, you'll be treated to a myriad of stars. [Catch the 'Winter Football' and Other Asterisms with Mobile Astronomy]

Battling the cold

If you plan to be outside for long on these frosty nights, remember that enjoying that starry winter sky requires protection against low temperatures. This was a bitter lesson that the very first director of New York's Hayden Planetarium, Clyde Fisher, learned one night in 1931, when he and noted meteor expert Charles Olivier journeyed to the Catskill Mountains to view some meteors. It was on a mid-November night when "the air bit shrewdly," yet Fisher wore silk socks and an overcoat, and was soon doing a tap dance to keep his feet from freezing. In contrast, Olivier dressed like he was going to Alaska.

But even Olivier was probably overdressed, to the point that it might have been difficult to move around. You can properly protect yourself against the elements without suiting up like an astronaut about to walk on the moon.

One of the best garments I have found for winter skywatching is a hooded ski parka, which is lightweight yet provides excellent insulation. I also like ski pants, which are superior to ordinary denims or corduroys. Of course, you should also invest in a good pair of gloves that are specially designed for intense cold. If you plan to stay outside for longer than, say, a half-hour, consider bringing along a thermos filled with something hot, like coffee, tea or cocoa.

Stay away from alcohol!

And as Fisher would certainly advise, remember your feet! While two pairs of warm socks in loose-fitting shoes are often adequate, for protracted observing on bitter-cold nights, it is even better if you wear insulated boots — even if there isn't any snow or ice on the ground.

So, clear, starry skies to all ... and remember to stay warm!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.