Huygens Data Paint Turbulent Picture of Titan

The Huygensprobe landed on Saturn's moon Titan in 2005, but it never encountered chilly seasof liquid methane as mission scientists had hoped--it landed in a mud field.

In spite ofthe disappointment, scientists have recreated a turbulent picture of Titan'satmosphere using data from sensors intended to measure oceanic properties. Inaddition to showing Huygens probably plunged through turbulent methane iceclouds, the research may aid in the design of balloon probes for future Titanmissions.

?We knewHuygens had a bumpy ride down to Titan?s surface. Now we can separate outtwenty minutes of air turbulence--probably due to a cloud layer--from othereffects such as cross winds or air buffeting,? said Mark Leese, a Huygensproject manager at The Open University in the U.K.

TurbulentTitan

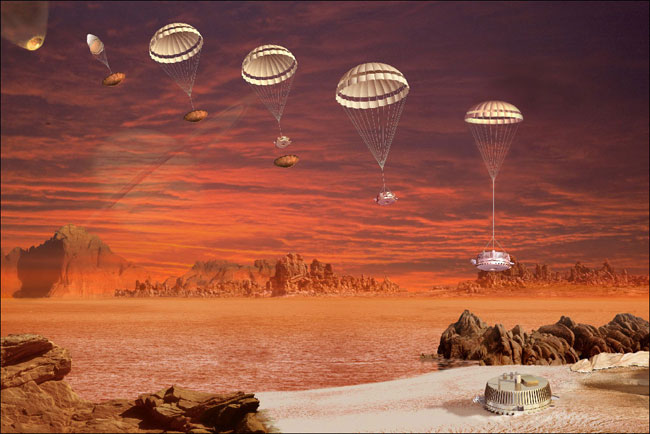

The Huygensprobe jettisoned off of theCassini probe on Dec. 25, 2004 and reached Titan's surface in Jan. 14,2005, deploying a parachute after entry into the moon's planet-like atmosphereto begin a 2.5-hour descent.

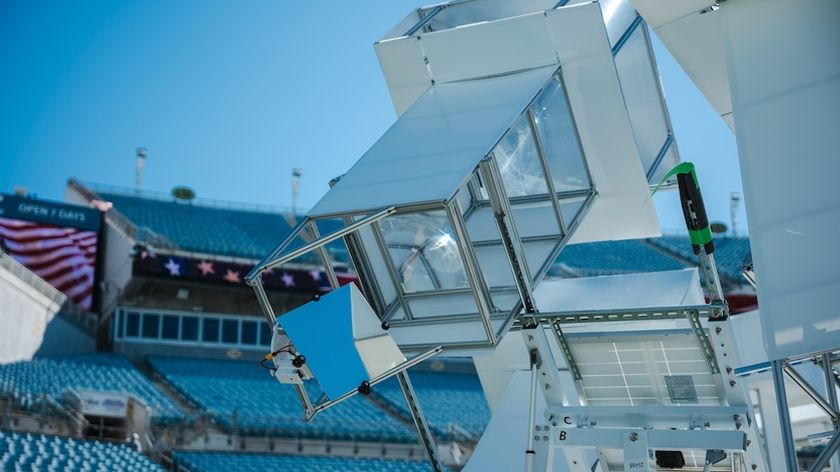

Huygensengineers did not intend to precisely measure the minor, chaotic changes in airknown as turbulence, but Lorenz and his team gleaned such data by looking at informationfrom two of the probe's sensors. One of the two, a "liquid density sensor,"was designed to measure the properties of Titan's purportedmethane seas if the probe had floated on one.

"Althoughnever designed with atmospheric measurements in mind, this device works as aweakly damped accelerometer," write the study's authors in an upcomingissue of the journal Planetary and Space Science. Accelerometers measurechanges in speed at extremely minute scales. NASA, for example, uses one onNASA's space shuttle leading wing edges to detect vibrations caused bymicrometeoroid impacts, among other phenomena.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Lead authorRalph Lorenz, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University inBaltimore, Md. Lorenz and his colleagues partnered the density sensor's data withthat from a pendulum-like "tilt sensor" to create a play-by-playpicture of Huygens' atmospheric dive.

"Suchinformation may offer insights into the meteorological processes prevalent onTitan, a world believed to share many characteristics with the Earth,"Lorenz said.

Theresearchers found that Huygens may have plunged into icy methane cloud layer--whichscientists have proposed to create a chilly methane "rain" --about12? to 19 miles (20 to 30 kilometers) above the moon's surface.

Balloonboon?

Althoughthe turbulence findings may not give airline passengers on Earth relief fromthe nauseating buffets of wind, the information could be used to help designballoon-like probes.

"FutureTitan exploration might use lighter-than-air vehicles, which would have tocompensate for wind gusts in order to keep above targets of interest forsampling," the study's authors said.

Scientistsimagine such balloons would be outfitted not only with cameras to detail out themoon's surface, but also spectrometers that could map mineral deposits onTitan. NASA, however, has neither approved nor scheduled such a mission.

Lorenz andhis colleagues hope to use more Huygens data, including that from radioemissions, to create a more detailed reconstruction of Huygens' descent as wellas Titan's nitrogen-thick atmosphere.

- VIDEO: Strange Saturn Hexagon

- GALLERY: Imaging Saturn and Titan

- Complete Cassini-Huygens Mission Coverage

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dave Mosher is currently a public relations executive at AST SpaceMobile, which aims to bring mobile broadband internet access to the half of humanity that currently lacks it. Before joining AST SpaceMobile, he was a senior correspondent at Insider and the online director at Popular Science. He has written for several news outlets in addition to Live Science and Space.com, including: Wired.com, National Geographic News, Scientific American, Simons Foundation and Discover Magazine.