On Titan, A Dreary Drizzle

Future settlers take note: Galoshes and umbrellas are a must on Saturn's moon Titan,where mornings are eclipsed by dreary drizzles of methane.

Getting drenched would be the least of your worries, however, as Saturn's largest satellite plunges to a bone-chilling -297 degrees Fahrenheit (-183 degrees Celsius) at the surface and its swirling orange atmosphere is full of hydrocarbons, such as methane, which is natural gas—and no oxygen.

“Crude oil minus the sulfur is a decent estimate of what the haze is,” said lead author of a new study of Titan's weather, Mate Adamkovics, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley. “Really we don't know for sure, but I would describe it as tiny particles of wax that are really, really cold, or waxy snowflakes.”

Adamkovics added that while scientists are not sure how toxic the particles are, the lack of oxygen would be much more of a hazard.

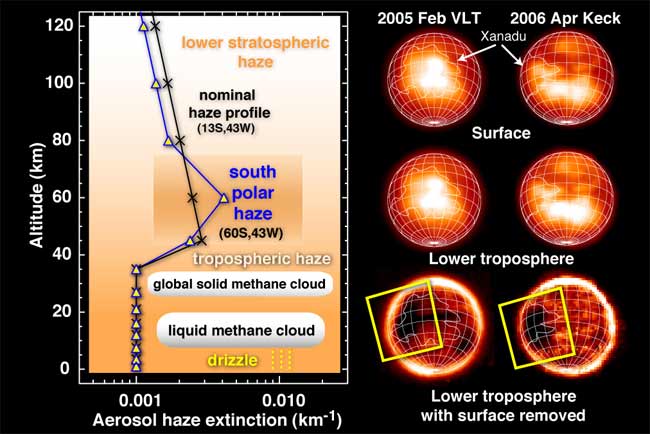

Using near-infrared images from Hawaii's W. M. Keck Observatory and Chile's Very Large Telescope, the team of astronomers reveals a nearly global cloud cover at high elevations on Titan. They also found persistent morning drizzle made of methane over the western foothills of Xanadu, Titan's largest “continent.”

Measuring about 3,200 miles (5,150 kilometers) across, Titan is larger than Mercury and Pluto and about 40 percent the diameter of Earth. It is the only moon in the solar system with a dense, planet-like atmosphere (10 times denser than Earth's).

As is the case on Earth, where features like lakes and mountains can morph and direct weather systems, Titan's terrain also could be a rain maker.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

“Titan's topography could be causing this drizzle,” said study team member Imke de Pater, an astronomy professor at UC Berkeley. “The rain could be caused by processes similar to those on Earth: Moisture laden clouds pushed upslope by winds condense to form a coastal rain.”

Cloudy observations

The new findings, detailed in the Oct. 11 issue of Science Express, an online version of the journal Science, provide strong evidence supporting past cloud-cover observations and possible indicators of methane drizzle over parts of Titan.

In 2005, the Huygens probe that had been aboard NASA's Cassini spacecraft gathered data supporting the existence of frozen methane clouds at higher elevations and liquid methane clouds, with possible drizzle, lower in the atmosphere.

But the extent of such clouds was unclear. “A single weather station like Huygens cannot characterize the meteorology on a 'planet-wide' scale,” said UC Berkeley astronomer Michael Wong, who was part of the recent study.

And until now, liquid rain was inferred from reports of lakes of liquid hydrocarbon, which scientists presumed were filled by methane precipitation.

Dreary Titan

Adamkovics and his team analyzed infrared measurements throughout Titan's atmosphere. By subtracting out the absorption and scattering due to aerosols low in the atmosphere as well as light from the surface, they were left with a signal that was due to actual droplets of liquid methane. Using a “radiative transfer model,” the scientists distinguished between miniscule drops inside clouds and larger ones that form drizzle.

The results paint a dreary picture with a global cloud of frozen methane hovering at a height of about 16 to 22 miles (25 to 35 kilometers), liquid methane clouds below 12 miles (20 kilometers) and drizzling methane at lower elevations.

“We show that the solid cloud covers the globe and the drizzle happens predominantly in the morning,” Adamkovics told SPACE.com.

The methane droplets inside Titan's clouds are estimated to be a thousand times larger than those in terrestrial clouds. Yet, both contain similar moisture contents, Adamkovics said. And if a cosmic cloud wringer were to empty out Titan's clouds, about six-tenths of an inch (1.5 centimeters) of water would blanket the moon's surface.

The drizzle or mist appears to dissipate after about 10:30 a.m. local Titan time, which is about three Earth days after sunrise. Titan takes nearly 16 Earth days to rotate once.

- Video: Parachuting onto Titan

- Top 10: The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- Image Gallery: Saturn and Titan

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.