As soon as darkness falls these evenings, step outside andlook skyward. What is the most prominent and easiest star pattern to recognize?If you live in the Northern Hemisphere you only need to look overhead andtoward the north where you will find the seven bright stars that comprise thefamous Big Dipper.

For most sky gazers, the Big Dipper is probably the most importantgroup of stars in the sky. For anyone in the latitude of New York (41 degreesnorth) or points northward, it never goes below the horizon. It is one of themost recognizable patterns in the sky and thus one of the easiest for thenovice to find.

In other parts of the world, these seven stars are known notas a Dipper, but as some sort of a wagon. In Ireland, for instance, it wasrecognized as "King David's Chariot," from one of that island's earlykings; in France, it was the "Great Chariot." Another popular namewas Charles's Wain (a wain being a large open farm wagon). And in the British Isles, these seven stars are known widely as "The Plough."

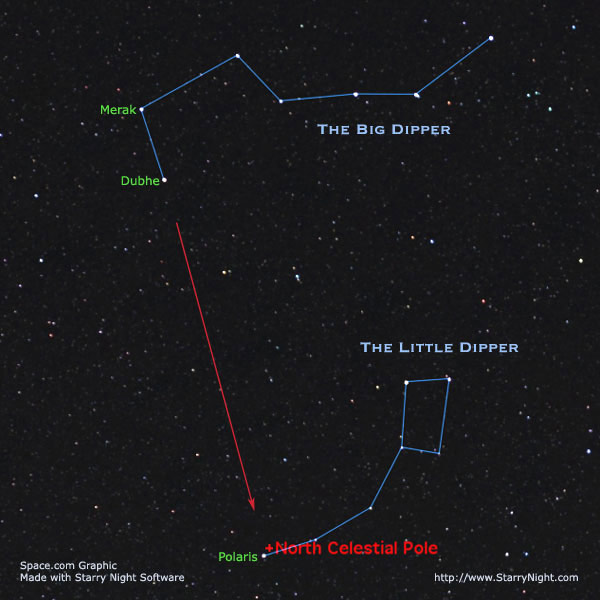

Of greatest importance is the ability to utilize the BigDipper to locate Polaris,the North Star. This is made possible by the two bright stars that mark theouter edge of the bowl of the Big Dipper. These two stars — Dubhe and Merak — are known as the "Pointers," because they always point to Polaris. Just draw aline, in your imagination, between these two stars and prolong it about 5 timesthe distance between these two stars and this line will ultimately hit amoderately bright star. That will be Polaris.

The Southern Cross

But for those who live in the Southern Hemisphere, it's not theBig Dipper that people choose as their guide to the night sky — but rather,it's the constellation known as Crux, the SouthernCross. Those south of the equator (where the season is now midautumn),need only cast a glance toward the south where they'll see the distinctiveshape of the Cross hanging well up in the sky. To some, it looks more like akite, though the Cross is clearly outlined by four bright stars, two of which,Acrux and Becrux, are of the first magnitude. From top to bottom, Crux measuresjust 6 degrees — only a little taller than the distance between the Pointerstars of the Big Dipper. In fact, the Southern Cross is the smallest (in area)of all the constellations. Like the Big Dipper of the northern sky, theSouthern Cross indicates the location of the pole and as such is often utilizedby navigators. The longer bar of the Cross points almost exactly toward thesouth pole of the sky which some aviators and navigators have named the"south polar pit" because, unfortunately, it is not marked by anybright star.

It is thought that Amerigo Vespucci was the first of theEuropean voyagers to see the "Four Stars," as he called them, whileon his third voyage in 1501. But actually, Crux was plainly visible everywherein the United States some 5,000 years ago, as well as in ancient Greece and Babylonia. According to Richard Hinckley Allen (1838-1908), an expert in stellarnomenclature, the Southern Cross was last seen on the horizon of Jerusalem about the time that Christ was crucified. But thanks to precession — anoscillating motion of the Earth's axis — over the centuries, the Cross ended upgetting shifted out of view well to the south.

Immediately to the south and east of the Cross is apear-shaped, inky spot, about as large as the Cross itself, looking like agreat black hole in the midst of the Milky Way. When Sir John Herschel firstsaw it from the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa in 1835, it is said that hewrote his aunt, Caroline about this "hole in the sky." Indeed, fewstars are seen within this hole and it soon became popularly known as the"Coalsack" which initially was thought to be some sort of window intoouter space. Today we know that the celebrated Coalsack is really a great cloudof gas and dust that absorbs the light of the stars that must lie beyond it.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Limits of visibility

There are likely a number ofreaders who have never seen either the Big Dipper or the Southern Cross andmight wonder about how far they might have to travel in order to get a view ofthem. Coincidentally, at this time of the year, both are attaining theirhighest positions in the sky at the same time: right after nightfall in lateMay and early June. To see Crux, one must go at least as far south as latitude25 degrees north. That means heading to the Florida Keys in the continental United States, where you'll see it just lifting fully above the southern horizon.

So far as seeing the BigDipper, you must go north of latitude 25 degrees south to see it in itsentirety. Across the northern half of Australia, for instance, you can now justsee the upside-down Dipper virtually scraping the northern horizon soon aftersundown. In fact, it's just the opposite effect as opposed to those who live innorth temperate latitudes (like New York), whose inhabitants see the Dipper ata similar altitude above the northern horizon on early evenings in lateNovember or early December — except the Dipper appears right-side up!

Interestingly, the Big Dipper and the Southern Cross havealso been depicted on a number of flags.The Dipper is depicted on the Alaskan state flag. The Southern Cross can befound on the national flags of Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Samoa and Brazil. Interestingly, on the flags of Australia, Brazil, Papua NewGuinea and Samoa, Crux is represented with five stars, while on the New Zealandflag only the four brightest stars of the Cross are depicted, the faintestfifth star (Epsilon Crucis) being omitted.

- Online Sky Maps and More

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- Astrophotography 101

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and otherpublications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.