Phoenix Gets Close-up Look at Mars Dirt

NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander got its first (very) close-up look at Martian soil, scientists said Friday.

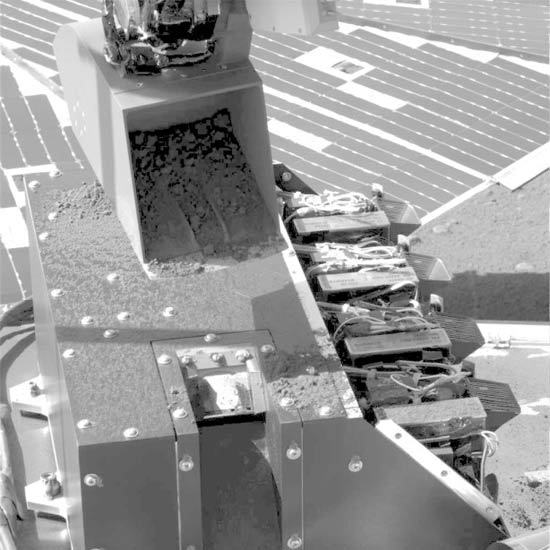

Phoenix used its robotic arm scoop to deliver a sample of the soil around the landing site to its optical microscope, which can zoom in on soil particles as small as 2 microns across (the size of some bacteria) — the smallest scale ever seen on Mars.

"This is the highest resolution image of the soil of Mars," said the mission's geology team leader, Tom Pike of University College London. "This is the first time we've reached down to this level."

The microscope images show a wide variety of particle sizes, colors and types in the soil. One of the particles viewed through the microscope is just 50 microns across, a little less than diameter of human hair. It is greenish in one part, which Pike says could be olivine, a mineral seen elsewhere on Mars. The other part of the particles "the very characteristic orange color" of the Martian soil as a whole, Pike said.

Another particle is black, glassy and more rounded in its shape. "This may very well be a volcanic glass," Pike said.

The microscope images also showed that the clumpy tendencies of the soil go right down to the microscopic level. The green-and-orange particle is actually "a clump of even finer particles," Pike said.

"It's obviously a very sticky material right down to the finest scale," he added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The tendency of the soil particles to stick together has caused some problems for the mission. When the first soil sample was delivered to the Thermal and Evolved-Gas Analyzer (TEGA) on June 6, it got stuck behind the screened entrance to the instrument. After using a vibrator on the machine, the soil eventually loosened and fell into TEGA. Results from TEGA's first analysis should be sent back to mission scientists next week.

To get around the clumping problem, scientists are now using a "sprinkle" technique to deliver samples. The scoop on the robotic arm is tilted forward, and then a rasp at the end (designed for scraping up hard ice) is run to dribble the soil into the instrument, like a salt shaker. This was the technique used to deliver the sample to the microscope.

Phoenix's microscope hasn't been the only busy instrument aboard the lander. The craft's stereoscopic imager has continued taking high-resolution, color images of the area around the landing site (these will eventually be stitched together into a 360-degree panorama).

The robotic arm continued digging into its first two trenches, Dodo and Baby Bear, revealing more of the unidentified white material seen under the surface layer of regolith. Mission scientists are still debating whether the white material is ice, or a layer of salt minerals that could have formed above the ice layer.

To find out what the material is, "we need to gather a sample of it and put it in our instruments," said Phoenix principal investigator Peter Smith of the University of Arizona. "We have just the right instruments on the surface here to answer those questions."

TEGA in particular will be useful: It is extremely sensitive to water, so if the white material is ice, TEGA should sniff it out right away.

The meteorological instruments have also continued observing the Martian atmosphere. Images of the air above Phoenix as well as lidar readings show that "there's lots of dust in the atmosphere," said Phoenix science team member Nilton Renno.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.