Twin Stars Born 500,000 Years Apart

Bouncingbaby stars considered identical twins were oddly born 500,000 years apart, anew study finds.

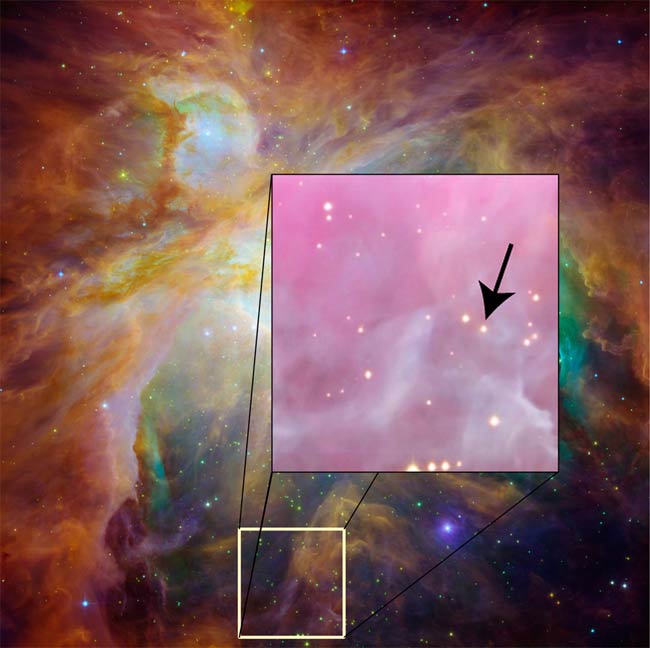

The newlydiscovered star pair is located in the Orion nebula, a nearby "maternityward" bustling with stellar-birth activity and located 1,500 light-years fromEarth. Onelight year is the distance light will travel in a year, or about 6 trillionmiles (10 trillion kilometers).

Theastronomers who discovered the binary found that the stars show identical massesand compositions, elevating the pair to identical twin status. However, theirrelative brightness and other physical features differ, suggesting one star in Par1802 formed earlier than the other.

Until now,astrophysicists had assumed binary stars form at about the same time. And sothe discovery of these not-so-similar twin stars, detailed in the June 19 issueof the journal Nature, puts a new wrinkle in star formation theories.

Winking babystars

AstronomersKeivan Stassun of Vanderbilt University and Robert Mathieu of the University of Wisconsin-Madison headed up the study.

They siftedthrough 15 years' worth of observations of thousands of stars, looking forstellar winks, which suggest a star has just eclipsed its partner. In eclipsingbinaries, the two stars as viewed from Earth revolve around an axis that isedge-on to us. Periodically, the stars eclipse, or pass in front of, eachother.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sureenough, they saw a dip in light where the new eclipsing binary resides.

Both starsare about 41 percent that of the sun's mass. Each star is about 1.7 to 1.8times the size of the sun, though the astronomers estimate one could be about10 percent larger than the other.

Theobservations come from the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona and theSMARTS telescopes at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.

Stellargenetics

Likehumans' genetic material, mass and composition for stars can be akin todestiny, according to Stassun. Human identical twins, which come from the sameegg, carry matching DNA and everything that comes with it, including spitting-imagelooks.

And that'swhat astronomers would've assumed about two same-mass starsorbiting each other.

"Themass of a star is the physical characteristic that, more than anything else, determineshow the star will go through its life. Mass is destiny for a star," Stassuntold SPACE.com. "If you have two stars with the same mass, theirdestinies ought to be the same. Or so we thought."

Stassun andMathieu found some glaring differences. One star is twice as bright as itssister. This showy twin also has a surface temperature that's about 300 degreeshigher than its twin's.

Birthorder

Thesefeatures make sense with a birth-order scenario suggested by the astronomers.

Here's how theythink it works:

WithinOrion's stellar nursery, cloudlets of gas and dust are slowly collapsing inunder their own weight, i.e. celestial conception. As the clumps of gas anddust condense and get smaller and smaller, they heat up until eventually theylight up as full-fledged stars.

Mostcloudlets pop out newborn stars at roughly the same time, Stassun said. But forthe newly discovered twins, one star likely emerged roughly a half million yearbefore its sibling.

That meansthe elder star would be slightly ahead of its sibling in the star-formationprocess and hence would have shed some of its heat and contracted more,explaining why one star (the elder) has a smaller size, lower temperature andglows fainter than the younger one. Since the older star has contracted more,it just crams the same mass into a smaller package.

"Ourbest interpretation at this point is that the reason we're seeing thesephysical differences is because there was a birth order between thetwins," Stassun said. "One of them was born a little before the otherone."

Stassunsaid they aren't sure "what was going on when the two stars were still inthe womb; was one being fed more than the other?"

Astronomersspeculate stars tend to comein pairs, though eclipsing binaries are less common. And finding identicaltwins eclipsing, to boot, is like spotting that needle in a haystack, Stassun said.

The studywas funded by the National Science Foundation and a Cottrell Scholar award fromthe Research Corporation.

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Video: When Stars Collide

- Vote: The Strangest Things in Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.