Scientists Get the Scoop on Moon Exploration

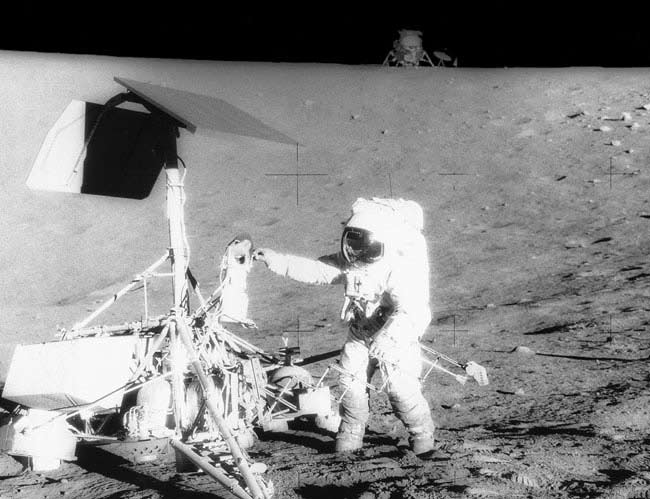

When astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean stepped out of theApollo 12 lunar module in November 1969, they were within walking distance ofSurveyor 3, an unmanned U.S. spacecraft that had landed in April 1967.

The Apollo landing site was picked on purpose. Surveyor 3 hadspent more than two years exposed to the moon's harsh vacuum, intense cosmicradiation, bombardment by meteoroids and extreme temperature swings. NASAengineers wanted to know how metals, glass and other spacecraft buildingmaterials held up.

Bean and Conrad took dozens of photographs and measurements, andremoved parts from the robotic lander, including a small scoop at the end ofSurveyor's extendable arm that had dug into the lunar dirt.

The scoop, a camera, and other artifacts were returned to Earth,analyzed, then put in storage, NASA explained in a recent statement. At somepoint in the intervening four decades, the scoop, owned by Johnson SpaceCenter, was transferred on permanent loan to a space museum in Kansas. Thenrecently researchers at NASA's Glenn Research Center (GRC) realized the littlescoop could hold big secrets.

When NASA returnsto the moon, there will be plans to dig.? The rocky, dusty lunar soil,called "regolith," contains natural resources, from oxygen to water ice,which could help support a colony.

But while terrestrial soil is moist and rounded by weather, lunarregolith is a dry,glassy substance pounded into dusty smithereens by eons of meteoriticbombardment.

"To design lunar digging equipment, we need to predict theforces required to move a scoop or other implement through lunarregolith," said Allen Wilkinson, team leader of the ISRU (In-Situ ResourceUtilization) Regolith Characterization team at the Glenn Research Center.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Surveyor 3 and a sister ship Surveyor 7 actually dug into the Moonand measured how hard their drive motors had to work to scoop, press, andscrape the soil. To interpret those measurements more than 40 years later,however, Wilkinson's team needs to know the dimensions of the Surveyor scoops.Unfortunately, they learned, the blueprints had been lost. Only a scoop itselfcould provide the answer.

That sent Wilkinson to Hutchinson, Kansas, in April 2007 to borrowthe Surveyor 3 scoop from the Kansas State Cosmosphere in order to makedetailed measurements.

Measuring the scoop, however, would prove to be no simple matter.You can't just lay a ruler along the scoop and read off the dimensions. Indeed,you can't touch it at all. The Surveyor 3 scoop is in an airtight triangularcontainer, and NASA curators do not wish the scoop to be removed becausehandling in air will degrade the historical fidelity of the unique artifact.

So the Glenn team borrowed photogrammetry apparatus from theKennedy Space Center. Photogrammetry is a technique of measuring objectsstrictly from photographs. They have a photographic studio setup with a whitebackground.

GRC team member Juan Agui, an expert in digging force experiments,photographed the scoop in its container next to a standard photogrammetry cube,which has a precise checkerboard pattern on it. Then, using software, RobertMueller of the Kennedy Space Center extracted dimensions using mathematicaltriangulation, measuring from points on the scoop to points where corners ofdark checks meet on the cube. The software was developed for the ColumbiaAccident Investigation Board activity.

"Photogrammetry is pretty good," Agui said. "We gotmeasurements of the scoop accurate to 0.030 or 0.040 inch," or about 1millimeter.

They've since constructed a replica of the scoop and now they areusing it to dig into simulated lunar regolith.

The replicated scoop plunges into a rectangular "soilbed" filled with JSC-1a, a man-made moondust substitute that closelymatches the known properties of lunar regolith, while a computer monitorsbearing forces.

"The measurements appear to be close to reproducing [thebest] Surveyor 7 data from the Moon," Agui said.

With this test bed in place, the team can now test alternate scoopdesigns and refine theories of lunar soil mechanics.

"Obtaining the Surveyor replica really made the difference,"Agui said.

- Video: A New Era of Space Exploration

- Video: Moon meets Rover

- Images: Future Lunar Base

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.