Water Discovered in Moon Samples

Waterhas been found conclusively for the first time inside ancient moon samplesbrought back by Apollo astronauts. The discovery may force scientists to rethinkthe lunar past and future, although uncertainty remains about how much waterexists and whether future explorers could extract it.

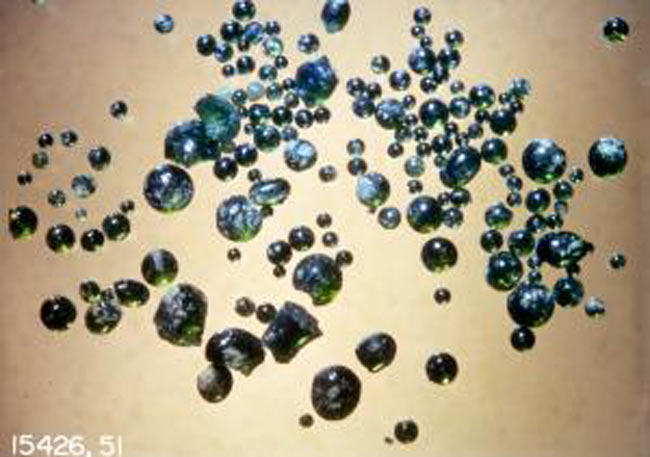

Thewater was found inside volcanic glass beads, which represent solidified magmafrom the early moon?s interior. The news swept through much of the scientificcommunity even before being detailed in the journal Nature this week.

?Thisreally appears to have changed the rules of the game,? said Robin Canup,astrophysicist and director of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder,Colo., who was not part of the team that made the discovery. ?The assumptionhas been that the moon is dry.?

Revisinglunar history

Scientistshave long assumed the moon was dry because of its violent birth roughly 4.5billion years ago. The leading theory holds that a Mars-sized planet smashed into Earth and tore off moltenpieces that eventually formed into the moon. Most scientiststhought that any water in the developing lunar body would have vaporized and beenlost to space.

?Ifthere was a lot of water in the early moon, then that is new for sure,? saidBen Bussey, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University AppliedPhysics Laboratory who also was not involved in the new study. ?People willhave to think about that when they think about how the moon evolved.?

Theearlier thinking about the moon?s lack of water meant researchers struggled toeven get funding to search for counter-evidence.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

?Ithought that if we were really lucky we would get to see it,? said AlbertoSaal, a geochemist at Brown University and lead author on the Naturestudy. ?Like everybody else, I was thinking our chances were low.?

Adelicate proposal

Saal?sgroup examined lunar samples brought back from the Apollo missions of the 1960sand 1970s. The glass beads range in color from green to yellow-brown to red,depending on their elemental chemistry.

Suchbeads formed from droplets of molten lava that spewed from fire fountains reachingdown deep within the primitive lunar interior. Saal?s group measured the beads'elemental makeup to ensure they came from lunar volcanic activity and not fromthe impact event that formed the moon.

Theresearchers also ruled out the chance that such beads could have becomecontaminated by outside forces such as hydrogen — an element of water — fromthe solar wind.

Othershad tried and failed earlier to find water in similar samples, but one of Saal?scollaborators had developed improved detection methods using a technique calledsecondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS).

?Forthe past four decades, the limit for detecting water in lunar samples was about50 parts per million (ppm) at best,? said Erik Hauri, geochemist at theCarnegie Institution in Washington, D.C. and co-author on the study. ?Wedeveloped a way to detect as little as 5 ppm of water.?

Thegroup found up to 46 ppm of water within the glass beads. Saal and hiscollaborators then used modeling to estimate how much water originally existedin the magma within the moon?s interior, knowing some water would have escapedthe molten droplets as a gas on the surface.

Thatled to estimates that the glass beads may contain 745 ppm of water — strikingly similar to solidified lava thatcame up from the Earth?s upper mantle through undersea vents. However, Saal?sgroup gives 260 ppm of water as the most certain figure for now.

Followthe water

Justfinding water at all could lead to a sea-change in how scientists view the earlymoon — either the moon held onto water from Earth during its violent creation,or else water gathered from elsewhere within 100 million years of the impactevent as the moon solidified.

Modelingdone on the Earth impact event suggests that our planet would have held ontomuch of its water, Canup explained. But such models say little about how muchthe moon could have held onto, and other questions remain unanswered even fromthis latest study.

?Themajor uncertainty I see is whether they?re sampling something that tells usabout the bulk composition of the moon, or whether they have sampled materialsproduced by a more limited water-rich part of the moon?s interior,? Canup said.

Knowingwhether water is highly abundant or relatively scarce within the moon couldalso have implications for lunar exploration, but not for near-future missionssuch as NASA?s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and Lunar Crater Observationand Sensing Satellite (LCROSS). The latter mission is slated to crash two spacecraft into the moon?s southpole in early 2009, in an attempt to find evidence of water ice hidden in thelunar craters.

Anysurface water ice likely formed fromcomets and other external bodies crashing into the moon and releasing theirwater, Bussey said, although he acknowledged the chance that some water vapordrifted to the poles during the moon?s early history.

Saal?sgroup will attempt to clear up some of those questions as they examine samplesfrom more Apollo missions. For now, their work stands as an example ofcontinuing to squeeze science out of an unexpected link between the past andfuture.

?Ithink it?s exciting that you keep getting results out of the Apollo samples.?Bussey said.

- What Makes Earth Special Compared to Other Planets

- VIDEO: Moon 2.0: Join the Revolution

- The Greatest Lunar Crashes Ever

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.