Small Satellite Designed to Spot Big Bad Asteroids

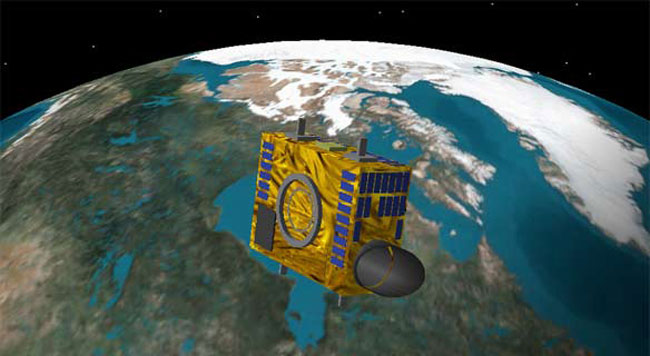

A tiny Canadian satellite isgearing up for a mission to hunt wayward space rocks that may pose a threat toEarth.

Only the size of a suitcase, the Near Earth ObjectSurveillance Satellite (NEOSSat) has a 5.9-inch (15-cm) telescope and weighsabout 143 pounds (65 kg). But it’s designed to hunt for threatening space rocksfrom Earth orbit, where the telescope can avoid interference from the planet’satmosphere.

“That’s why a small telescope in space can be a lot morecomparable to a large telescope on the ground,” said Alan Hildebrand, planetaryscientist at the University of Calgary and head of the asteroidsearch project for NEOSSat.

The Canadian microsatellite would also keep an eye onEarth’s satellite traffic for both U.S. and Canadian space commands, swivelingaround to target space rocks and satellites hundreds of times a day. That requiresa revolutionary turning system for the $12 million-satellite to do its job uponlaunch in early 2010.

Astronomers have particular interest in Near EarthObjects, because such objects might threatenEarth in the near or distant future. Nearby asteroids could likewise serve as targetsfor future spacecraft missions to investigate.

NEOSSat will also shed more light on the less famousInner Earth Objects, or asteroids found close to the sun within Earth’s orbit,mission managers said.

Point and click

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NEOSSat draws upon the technological heritage of astar-gazing mission called MOST(Microvariability and Oscillation of STars), which represented Canada’sfirst space telescope. But the newer microsatellite also boasts an attitudecontrol system based on spinning reaction wheels that allow it to turn quicklywithout consuming rocket fuel.

“We have to be able to point precisely at a chunk of skyfor 100 seconds,” Hildebrand told SPACE.com.? “Then you want to be ableto slew from one field to another as fast as possible.”

Such rapid response balances out with the need to keepthe space telescope steady on its target, whether peering at rocks in theasteroid belt or tracking a moving satellite.

“The attitude-control system is an absolute must,” saidBrad Wallace, scientist at Defense Research Development Canada (DRDC), theagency working with the Canadian Space Agency on NEOSSat.

However, the system’s reaction wheels don’t requireconsumable fuel to do their work. NEOSSat will draw power from solar panelsthat convert the sun’s energy into the required amount of electricity — just 45watts, or less power than an average light bulb.

Let’s go asteroid hunting

Low energy usage and a small size may make NEOSSat seempaltry compared to large ground telescopes that can cost $50 million and up.But scientists look forward to having a space telescope that can check outasteroids without bad weather or atmospheric background getting in the way.

“In terms of advantages of being in space, we’ve got 24/7availability,” Hildebrand said.

Ground telescopes face limits even with blue skies onEarth, because the atmosphere makes it harder to spot the faint light signalsfrom asteroids. NEOSSat reduces the background interference to one tenth ofthat on Earth, by going up roughly 435 miles (700 km) above the atmosphere.

Hildebrand hopes the microsatellite to discover at least100 Near EarthObjects per year once operational, and many more asteroids in the mainasteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Space traffic control

The microsatellite will also spend half its time trackingother satellites in orbit around Earth.

“Our first and foremost goal is to demonstrate satellitetracking capability,” said Wallace, who leads the DRDC science team focused ontraffic control.

Wallace’s team will spend NEOSSat’sfirst year testing new observing and tracking techniques, before handingover the keys to DRDC’s client, the Canadian Forces. That would allow the spacetelescope to take a more active role in helping the North American AerospaceDefense Command (NORAD) monitor the skies.

Satellite tracking requires slightly less of themicrosatellite’s capabilities, but Wallace also plans to test it on scenariossuch as tracking “lost” objects and doing hand-off coverage that picks up fromwhere another telescope began.

NEOSSat’s ability to take on dual responsibilities pointsto a future where microsatellites increasingly become the standard. The abilityto use more recent technology and commercial, off-the-shelf parts has only spedup the miniaturization process, Wallace said.

Earth orbit will undoubtedly get more crowded not longafter NEOSSat’s 2010 debut — DRDC has already begun work on a secondmicrosatellite that will monitor maritime shipping and travel on Earth.

- Video: The Asteroid Paradox

- Video: Take One Asteroid – A Recipe for Space Civilization

- GALLERY: Asteroids

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.