Solar Storms Smack a Comet

Astronomers have pieced together what appears to be the first direct evidence that solar storms can wreak havoc with comets, destroying the ion tails of icy wanderers in a collision of highly charged particles.

But the effect is not permanent and may serve as a marker for scientists trying to track solar storms known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs) as they blow out into space.

"What we have now is sort of a new tool of tracking these ejections," said Geraint Jones, co-investigator of the comet study and a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "It's like dropping paint into a flowing river of water."

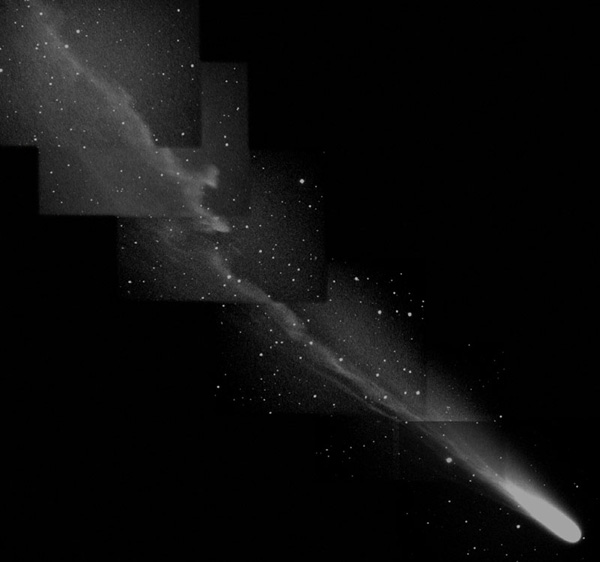

The ion tails of comets constantly stream away from the Sun, pushed back by solar wind blowing at about 894,774 mph (400 kilometers per second). But the charged particles of CMEs, among the worst of solar storms, can slam into a comet's ion tail at about 2.2 million mph (1,000 kilometers per second), causing kinks, scalloped patterns or disrupting the tail altogether, Jones' research found.

"We're still far from having a full understanding of what's going on [with CMEs]," Jones told SPACE.com.

But by watching comet tail behavior, researchers could learn more about changes in CME structure and speed as they move through space, researchers added.

"When [CMEs] move outward we know there's a lot of change, but that's it," explained Douglas Biesecker, a physicist with the Space Environment Center at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). "It would be a little more useful if there were a lot more comets out there."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The study, conducted by Jones and his colleague John Brandt at the University of New Mexico, appeared in the online version of the journal Geophysical Research Letters and will appear in the journal's upcoming print edition.

Comet distortion

At the heart of Jones' study is the comet 153P/Ikeya-Zhang, which passed through the inner solar system during spring 2002.

Jones and Brandt were able to identify specific interactions between CMEs and Ikeya-Zhang's ion tail by combining data from the sun-watching NASA/European Space Agency SOHO spacecraft and observations collected by amateur astronomers.

CME events recorded by SOHO instruments on March 2, March 9-10 and April 17 appear to have slammed into Ikeya-Zhang's ion tail each about a day or so after leaving the Sun. None of the CMEs distorted the comet's tail for more than an hour.

"On their own, the images were fascinating," Jones said. "But it was only when we put them all together that we saw how the changes were occurring that we realized what was happening."

Past observations had suggested that CMEs belched from the Sun could impact a comet's ion tail, including some stunning images taken by the SOHO spacecraft last year.

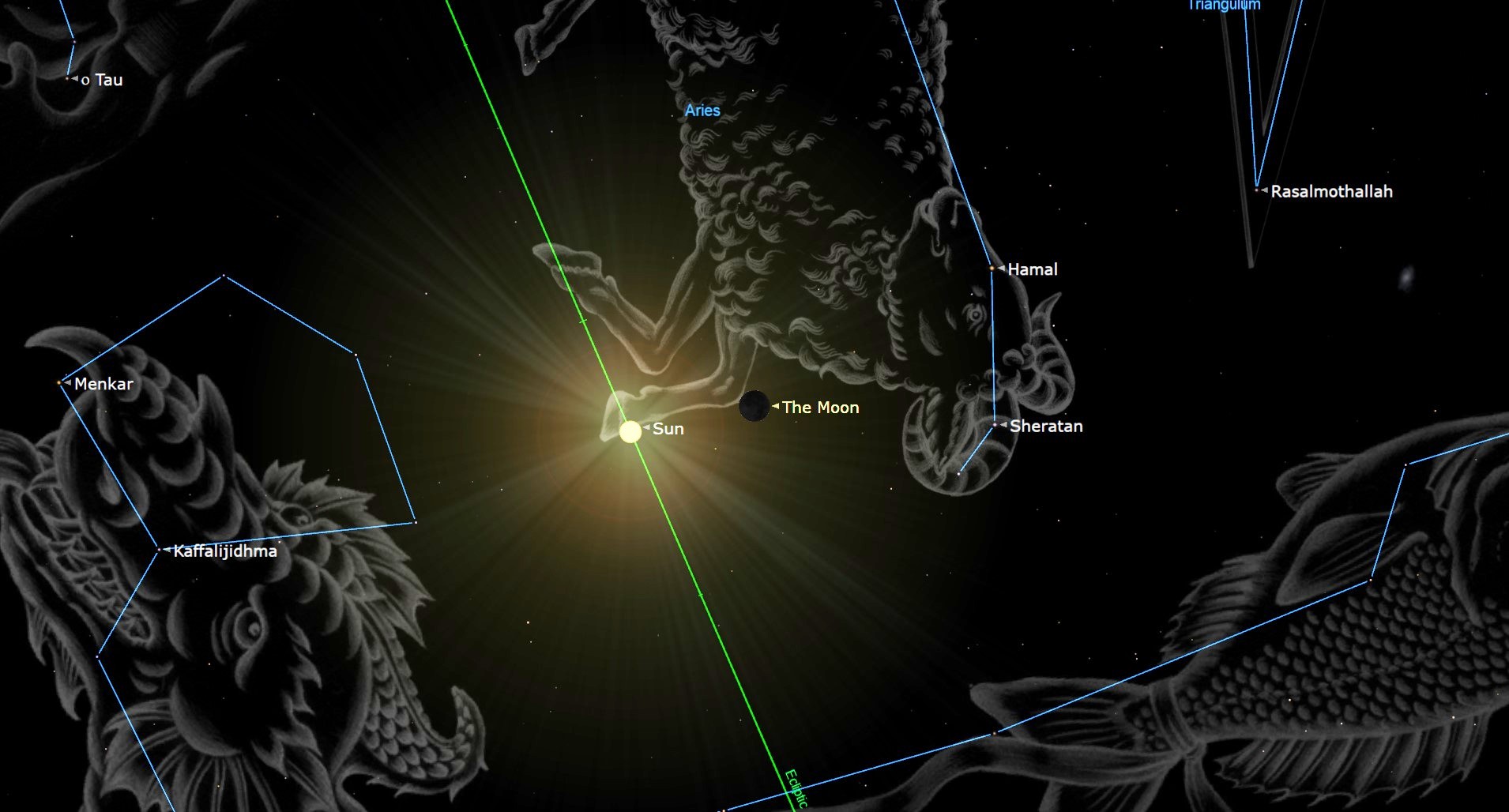

During February 2003, SOHO caught the comet C/2002 V1 NEAT swing by the Sun during a CME event, which researchers believed caused a kink in the icy wanderer's tail. The catch was a fortunate one, since NEAT's orbit brought it close to the Sun in astronomical terms, about one-tenth the distance between the Earth and the star or 0.1 astronomical unit (AU). One AU is about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

But Ikeya-Zhang's closest approach was about five times farther out at 0.51 AU at a distance where sun-watching spacecraft like SOHO can't see.

"Our studies have been limited in the past because we're limited to observations from spacecraft that are just measuring what the solar activity is near the Sun," Jones said.

Some instruments, such as the Solar Mass Ejection Imager aboard the Coriolis spacecraft in Earth orbit and the planned STEREO observatories are seeking a wider view on CMEs, Biesecker added.

Amateur assets

Part of the success behind the Jones-Brandt study is due to the readily available network of amateur astronomers from around the world, which heeded an open call for observations when Ikeya-Zhang swung past the Sun.

"Without the amateur astronomers, this research would not have been possible," Jones said. "It's a great example of how amateur astronomers and professionals can work together."

Jones hopes that cooperation will be repeated with a pair of comets that were observed earlier this year.

"They have more telescope time to themselves than we have sometimes as professional astronomers," said Biesecker of amateur skywatchers.

This article is part of SPACE.com's weekly Mystery Monday series.

- Comet Ikeya-Zhang Image Gallery

- More Comet News

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.