Cassini Prepares for Monday Flyby of Saturn Moon

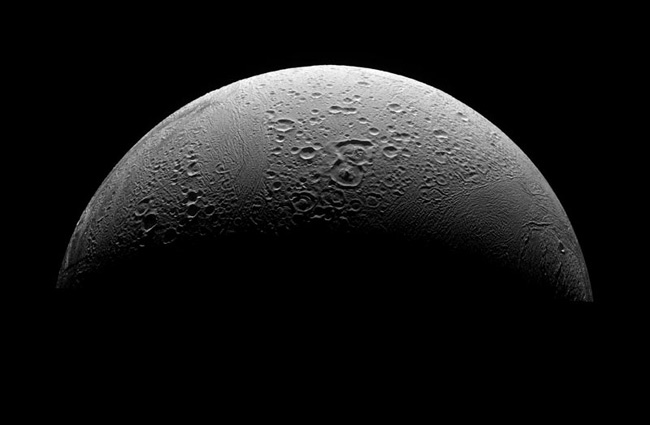

NASA'sCassini spacecraft is going to get another up-close-and-personal look atSaturn's moon Enceladus on Monday. Scientists hope the glimpse at fractures onthe icy moon's surface will provide clues as to how the jets spewing from themform.

Thespacecraft will zoom past the tiny moon just 30 miles (50 kilometers) over thesurface. Immediately after closest approach, Cassini will train its cameras ontothe fissures that run along Enceladus' south pole.

Jets of icywater vapor, first discovered by Cassini in 2005, erupt hundreds of miles intospace from these large cracks. The eruptionscreate a giant halo of ice and gas around Enceladus that helps supply materialto Saturn's E-ring.

Cassini'scameras, which collect light in the infrared, visible and ultravioletwavelengths, will aim to take high resolution images, as fine as 23 feet (7meters) per pixel, of the known active spots on three of the prominent"tiger stripe" fractures.

"Ourmain goal is to get the most detailed images and remote sensing data ever ofthe geologically active features on Enceladus," said Paul Helfenstein, aCassini imaging team associate at Cornell University in New York. "Fromthis data we may learn more about how eruptions, tectonics and seismic activityalter the moon's surface."

Infraredobservations, which detect temperatures on the surface, could help scientistsdetermine if water, in vapor or liquid form, lies close to the surface.

"We'dlike to refine our numbers and see which fracture or stripe is hotter than therest because these results can offer evidence, one way or the other, for theexistence of liquid water as the engine that powers the plumes," saidCassini team member Bonnie Buratti of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory inPasadena, Calif.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cassini'sobservations should also help determine the size of the ice grains that spewfrom the jets, as well as distinguish any other elements mixed in with theice, such as oxygen, hydrogen or organics.

"Knowingthe sizes of the particles, their rates and what else is mixed in these jetscan tell us a lot about what's happening inside the little moon," saidCassini team member Amanda Hendrix, also of JPL.

This nextflyby follows a previousclose approach in March during which Cassini was to sample the materialemanating from the plumes. A software glitch kept the spacecraft from carryingout its sampling mission, but it did return the most detailed imagesof the moon to date.

Monday'sflyby will be followed by two more in October. The attempt on Oct. 9 will alsotry to sample one of the icy plumes, while the Oct. 31 flyby will image thesurface again. Cassini, currently on an extended two-year mission following theJune 30 completion of its four-year primary mission, entered orbit at SaturnJuly 1, 2004.

- Video: Enceladus' Cold Faithful

- Cassini's Greatest Hits: Images of Saturn

- Special Report: Cassini's Journey's

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.