Strange New Comet Explains Old Mystery

Halley's comet, which lights up Earth's sky every 75 yearswith its glowing tail, is a bit of a scientific mystery.

So far theories have been at a loss to explain how itacquired its extremely unusual backwards orbit, but the recent discovery ofanother odd comet orbiting farther out in the solar system may shed light onHalley's origins.

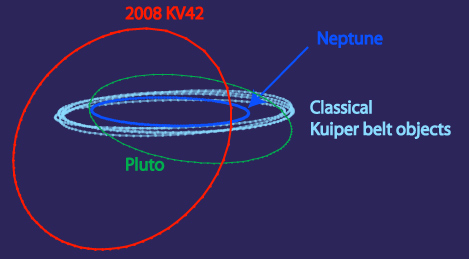

The newly-discovered comet 2008 KV42 circles the sun at atilt of 104 degrees compared to the main plane in which most of the planets andasteroids travel. The newfound oddball also orbits in reverse compared toalmost everything else. Scientists think it might represent an intermediatepoint between comets like Halley's and their progenitors in the far and totallyuncharted reaches of the solar system.

"The big mystery's been, how do you get comets like Halley's comet?"said astronomer JJ Kavelaars of the National Research Council of Canada, whoworked on the team that discovered KV42. "It's one of the most famouscomets known and we have no dynamic explanation for how it got into its orbit,and how it got to be there. Now we've found an object that could provide asource for a Halley-type comet."

KV42 was discovered at about 32 times the distance from theEarth to the sun, and the closest it swings to the sun is about where Uranusis. Researchers suggest the comet may have originated out in the distant Oortcloud of objects theorized to swarm in a sphere around the solar systemalmost 1 light-year out from the sun, or roughly a quarter of the way to thenext nearest star.

At some point, they think, gravitational interactions (suchas with Uranus or Neptune, or even a nudge from another star in the galaxypassing nearby the sun long ago) could have kicked the comet from its perch inthe lower level of the Oort cloud, about a tenth of a light-year away, down towhere it is now, orbiting beyond Neptune in a region known as the Kuiper Belt,where several other normally-orbiting rocky objects have been found.

This would explain how it got such a bizarre backward, orretrograde, and tilted orbit. If it originated in the spherical Oort cloud, thecomet could develop an orbit with any tilt at all, as opposed to most comets,which originate in the plane of the solar system, so must have an orbit in linewith the planets.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Eventually, researchers predict KV42 could get kicked down evencloser to the sun by interactions with the outer planets and the solar system'sheavyweight, Jupiter. Ultimately, both Halley's and KV42 are likely to end upslingshot out of the solar system altogether from gravitational interactionswith the planets.

Until now, physical models haven't been able to come up withan explanation for a comet like Halley's, but the researchers hope thediscovery of KV42 will allow physicists to plug a new half-way point into theirmodels to derive a reasonable evolutionary path for these objects.

"An orbit like this provides the road sign that saysthere must be a source of objects which could very plausibly be somethingrelated to the Oort cloud, which is feeding in slowly over the age of the solarsystem," research team member Brett Gladman of the University of BritishColumbia told SPACE.com. "It?s a pointer hopefully to a coherent model."

The researchers presented their discovery at the 10th"Asteroids, Comets and Meteors" meeting in Baltimore in July 2008.They first observed KV42 with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in Hawaii, andmade follow-up observations on the MMT telescope in Arizona, Cerro TololoInter-American Observatory (CTIO) 4-metre telescope in Chile, and Gemini Southtelescope of Canada?s Gemini Observatory, also in Chile.

- Image Gallery: Great Comets

- Comets Through Time: Myth and Mystery

- Video ? Comets: Bright Tails, Dark Hearts

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.