Hottest Planet Ever Discovered

In the hunt for extrasolar planets, a new find is shatteringrecords left and right.

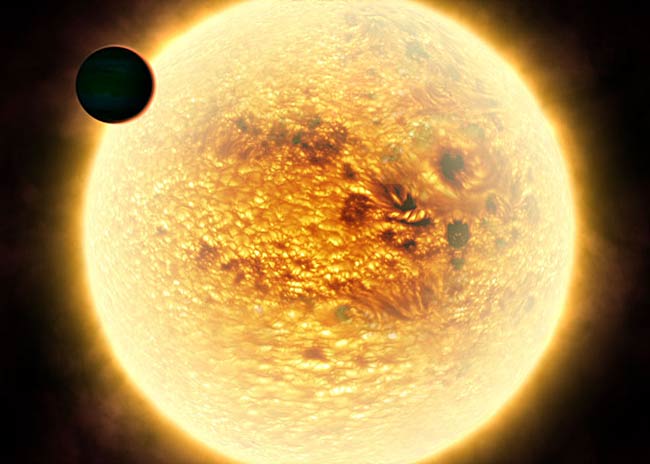

A planet called WASP-12b is the hottest planet everdiscovered (about 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit, or 2,200 degrees Celsius), andorbits its star faster and closer in than any otherknown world.

This sizzling monster whips its way around its parent starabout once a day (for comparison, the fastest-circlingplanet in the solar system, Mercury, orbits the sun once every 88 days).

To make such swift progress, the planet circles extremelyclose-in to its star ? about 2 percent of the distance from the Earth to thesun, in fact, or 2 million miles (3.4 million kilometers).

"WASP-12b is incredibly interesting, because we're at astage in the study of exoplanets where we're findingnew examples all the time," said Don Pollacco of Queen's University inNorthern Ireland, who is a project scientist for the SuperWASP (Super WideAngle Search for Planets) project that discovered WASp-12b. "It wasexciting because it was the shortest period and the hottest planet, but Isuspect there are even shorter period planets, and hotter planets tocome."

WASP-12b is a gaseous planet, about 1.5 times the mass ofJupiter, and almost twice the size.

The planet, which orbits a star 870 light years from Earth,is especially notable because it pushes the bounds of how close planets canever come to their stars without being destroyed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There is a limit because as a planet gets closer toits star, the radiation field gets more and more intense, and at some point thatwhole planet will be evaporated by its star," Pollacco told SPACE.com."Before, some people thought it was impossible to find planets that had 1-dayperiods. I think it's so early in the whole subject, and it takes a number ofobjects before you can start setting limits."

The planet is also so hot that its temperature matches thatof some stars. This planet, however, is definitely not a star because itsmass isn't nearly large enough for the internal thermonuclear reactions thatdefine stars.

WASP-12b is one of only about 50 extrasolar planets thathave been detected through the transit method, meaning they were found bymeasuring the dip in brightness of their parent star as they pass in front ofit and block part of its light.

"It's an incredibly hard way to detect planets, becausethe size of this dip when it moves across the star is very small,"Pollacco said. "These objects are difficulty to find, but they're incrediblyvaluable when you do find them because they tell you so much."

The transit method allows astronomers to not only note thepresence of a planet, but estimate its size, mass and density. And byestimating its distance from its star, researchers can deduce its roughtemperature, because the closer in an object is, the hotter it gets.

All the information scientists have so far about WASP-12bindicates that this fiery ball cozily circling its star is an odd case. Yetdiscoveries like this raise the question, are planets like this in fact morecommon in the universe than planetslike Earth?

"Is our solar system the freak, or are these othersolar systems the freaks?" Pollacco said. "Who knows? I suspect thatfor life to evolve as we know it, you have to have a special set ofcircumstances come together to produce very specific conditions."

The SuperWASP project, based in the UK, uses telescopes inSpain's Canary Islands and in South Africa to scan the sky searching fordistant planets that cross in front of their stars.

The discovery of WASP-12b was first announced in April 2008,though its distinction as the hottest and fastest-orbiting exoplanet wasconfirmed Oct. 11 at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society?sDivision for Planetary Sciences by co-discoverer Leslie Hebb of the Universityof St. Andrews in Scotland.

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Video: Planet Hunter

- Missing Link Between Planets and Stars Found

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.