One Mystery of Jet Streams Explained

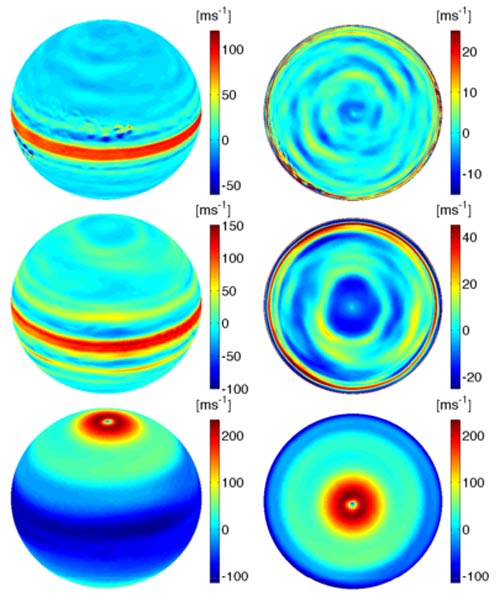

Planetary scientists have long puzzled over why fast-movingrivers of air called jet streams flow eastward at the equator of Jupiter andSaturn, but go westward on Uranus and Neptune. Now a new simulation has begununraveling that mystery by showing how turbulent thunderstorms create the jetstreams.

Whether a jet stream flows east or west seems to dependon the amount of water vapor in a planet's atmosphere — but researchers confessthat the "how" stilleludes them.

"Under these conditions, the eastward equator flowprefers low water vapor abundance," said Yuan Lian, an atmosphericdynamics researcher at the University of Arizona in Tucson. "The westwardequator flow prefers high water vapor abundance. However, we still don't knowexactly how this happens."

The equatorial jet stream goes westward onEarth, but all the other jet streams on our planet go eastward, including theone that frequently dipsdown from the Arctic to bring winter storms across North America.

Rivers of air

Jet streams feed on swirling eddies that can form thebasis of thunderstorms on giant planets. Eddies don't necessarily all mergetogether to form a jet stream — some can simply spin off their angular momentuminto the jet to sustain howling wind speeds.

Some jet streams have clocked in at 400 mph (644 km/h) onJupiter, and almost 900 mph (1,448 km/h) on Saturn and Neptune. Wind speedson Venus can hit almost230 mph (370 km/h).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"You have a little vortex that gets stretched outand sheared apart by the wind," said Adam Showman, a planetary scientistat the University of Arizona. "As it's shearing apart, it gives the jetstream a little push."

Eddies and vortexes themselves form from rising watervapor. The vapor condenses in the cooler upper latitudes of planet atmospheresand releases energy in the form of heat, which disturbs the surroundingatmosphere.

Simulating the flow

Showman and Lian estimated that Uranus and Neptunecontain 10 times as much water vapor as Jupiterand Saturn. They plugged the data into their simulation runs and found thatthey came up with jet streams with directions matching those observed on eachplanet.

"We took our best guess with our best models foreach of the planets," Showman told SPACE.com. "We did a bunchof simulations varying the water. Even if we don't think the planet has thatamount, it allows us to understand role of water in that simulation."

The simulations also came up with the 20 jet streams eachfor Jupiter and Saturn, as well as three jet streams each for Uranus andNeptune. Likewise, they produced simulated storms similar to thunderstorms previouslyspotted on Jupiter and Saturn.

Yet the question remains as to why jet streams at theequator go either east or west.

Stability, stability

Without knowing the details, researchers can onlyspeculate on water vapor condensation creating a topsy-turvyatmosphere. A more unstable atmosphere may result in jet streams thathappen to form in an eastward- or westward-running direction.

"When you have this occurring in a complicated 3-Dcirculation, it can develop latitudinal temperature differences," Showmannoted. "More water vapor means more temperature differences that changethe stability of the atmosphere."

However, a better understanding will have to wait forimproved simulations. Lian pointed out that the simulated jet streams did notquite reach the high speeds of real jet streams. The current model also ignoredsome processes such as precipitation, evaporation and cloud formation.

"We want to include as many factors as we can,"Lian said. "That way, we can probably produce jet speeds similar toobservations."

The findings were detailed at the 40th annual meeting ofDivision of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomy Society in Ithaca, NewYork.

- Video - Saturn's Hexagonal Storm

- Video - Sharpening Up Jupiter

- Cassini's Greatest Hits: The Best of Saturn

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.