If you go out and carefully study the sky near dusk or dawn, and you have relatively dark skies, the odds are that you should not have to wait more than 15 minutes before you see one of the more than 35,000 satellites now in orbit around Earth.

Most of these "satellites" are actually just "space junk" ranging in size from as large as 30 feet, down to about the size of a softball. The Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC) headquartered at Vandenberg AFB in California, keeps a constant watch on all orbiting debris. Try our Satellite Tracker from N2Y0.com and spot the International Space Station and more!

And in fact most satellites -- especially the bits of debris -- are too faint to be seen with the unaided eye. But depending on who's counting, several hundred can be spotted with the unaided eye. These are the satellites that are large enough (typically more than 20 feet in length) and low enough (100 to 400 miles above Earth) to be most readily seen a sunlight reflects off them.

The biggest

The International Space Station (ISS) is by far the biggest and brightest of all the man-made objects orbiting the Earth.

On-orbit construction of the station began in 1998, and is scheduled to be complete by 2011, with operations continuing until around 2015. More than four times as large as the defunct Russian Mir space station, the completed International Space Station will ultimately have a mass of about 1,040,000 pounds (520 tons) and will measure 356 feet across and 290 feet long, with almost an acre of solar panels to provide electrical power to six state-of-the-art laboratories.

Presently circling the Earth at an average altitude of 216 mi (348 km) and at a speed of 17,200 mi (27,700 km) per hour, it completes 15.7 orbits per day and it can appear to move as fast as a high-flying jet airliner, sometimes taking about four to five minutes to cross the sky. Because of its size and configuration of highly reflective solar panels, the space station is now, by far, the brightest man-made object currently in orbit around the Earth.

On favorable passes, the space station can appear as bright as the planet Venus, at magnitude -4.5, and some 16 times brighter than Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Some have made estimates as bright as magnitude -5 or -6 for the station (smaller numbers represent brighter objects on this astronomers scale).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And as a bonus, sunlight glinting directly off the solar panels can sometimes make the ISS appear to briefly "flare" in brilliance to as bright as magnitude -8; more than 16 times brighter than Venus!

Other things to see

Along with the ISS, you can also look for China's Tiangong-1 space laboratory, which has hosted visiting crews on Shenzhou spacecraft in recent years. Also visible to the naked eye is the Hubble Space Telescope.

Russia's Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, as well as SPaceX's Dragon and Orbital ATK's Cygnus capsules, are much smaller than NASA's space shuttles (which were also visible to the naked eye until they were retired in 2011). But they could potential be visible under the best observing conditions.

Viewing opportunities

During the northern summer, when the nights are the shortest, the time that a satellite in a low-Earth-orbit (like the ISS) can remain illuminated by the sun can extend throughout the night - a situation that can never be attained during other times of the year. Because the ISS circles the Earth about every 90 minutes on average, this means that it's possible to see it not just on one singular pass, but for several consecutive passes.

Moreover, because the ISS revolves around the Earth in an orbit that is inclined 51.6-degrees to the equator, there are two types of passes that are visible.

In the first case (we'll call it a "Type I" pass), the ISS initially appears over toward the southwestern part of the sky and then sweeps over toward the northeast.

About seven or eight hours later, it becomes possible to see a second type of pass (we'll call it "Type II"), but this time with the ISS initially appearing over toward the northwestern part of the sky and sweeping over toward the southeast.

Type I passes will initially be visible in the morning hours, prior to sunrise. By early July, Type I passes will be visible during the evening hours, just after sunset, while Type II passes will be occurring in the early morning. By late July, visibility of the Type II passes will have shifted into the evening hours.

When and where to look

So what is the viewing schedule for your particular hometown? You can easily find out by visiting one of these four popular web sites:

Each will ask for your zip code or city, and respond with a list of suggested spotting times. Predictions computed a few days ahead of time are usually accurate within a few minutes. However, they can change due to the slow decay of the space station's orbit and periodic reboosts to higher altitudes. Check frequently for updates.

Some passes are superior to others. If the ISS is not predicted to get much higher than 20-degrees above your local horizon, odds are that it will not get much brighter than second or third magnitude (10-degrees is roughly equal to the width of your fist held at arm's length). In addition, with such low passes, the ISS will likely be visible for only a minute or two. Conversely, those passes that are higher in the sky – especially those above 45-degrees – will last longer and will be noticeably brighter.

The very best viewing circumstances are those that take the ISS on a high arc across the sky about 45 to 60 minutes after sunset, or 45 to 60 minutes before sunrise. In such cases, you'll have it in your sky upwards to four or five minutes; it will likely get very bright and there will be little or no chance of it encountering the Earth's shadow.

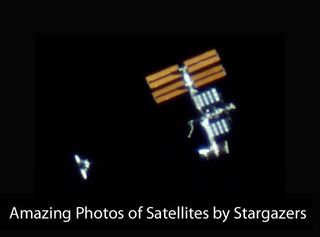

While the ISS looks like a moving star to the unaided eye, those who have been able to train a telescope on it have actually been able to detect its T-shape as it has whizzed across their field of view. Some have actually been able to track the ISS with their scope by moving it along the projected path. Those who have gotten a good glimpse describe the body of the Space Station as a brilliant white, while the solar panels appear a coppery red.

For evening passes, the ISS will usually start out rather dim and then tend to grow in brightness as it moves across the sky. In contrast, for the morning passes, the ISS will already be quite bright when it first appears and will tend to fade somewhat toward the end of its predicted pass. This is due to the change in the angle of sunlight hitting the vehicle.

Lastly, remember that in certain cases, the ISS will either quickly disappear when it slips into the Earth's shadow (during evening passes) or quite suddenly appear when it slips out of the Earth's shadow (during morning passes). This becomes increasingly more likely for passes that take place more than 90 minutes after sunset or more than 90 minutes before sunrise.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing photo of the Intenrational Space Station, satellite or any other night-sky sight that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send images and comments in to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was updated on March 18, 2016 to include new details about satellite tracking widgets, and other spacecraft that may be visible from Earth to the unaided eye. Correction: This article was updated 6/20/09 to name the Joint Space Operations Center as the organization that monitors space junk.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us@Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.