Two Moons to Pass in Front of Jupiter Wednesday Night

We are just a few months short of the 400thanniversary of the night of July 25, 1610, when Galileo first turned histelescope on Jupiter and spotted three star-like points of light to the left ofJupiter. A few nights later, he spotted a fourth object. Within a few weeks hehad followed these points of light long enough to deduce that they were fourmoons in orbit around Jupiter, one of the most significant discoveries in thehistory of science.

Astronomers are still following Jupiter?s moons; even thesmallest telescope will reveal their dance around mighty Jove. As with our ownmoon, they are involved in an endless series of eclipses, and related eventslike transits and occultations.

Wednesday night (Aug. 26) there is a rather special seriesof events involving Jupiter?s moons. To see them, you will need a telescopewith at least 90mm aperture; 125mm would be better.

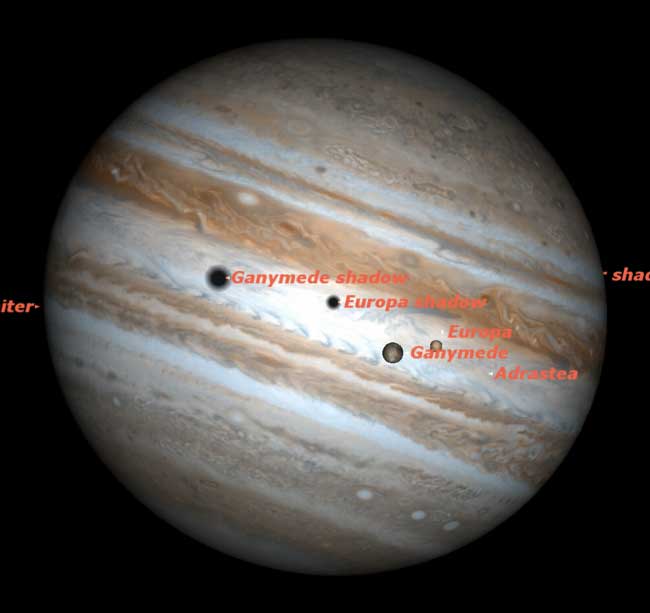

As Jupiter?smoons revolve around the planet, they sometimes pass in front of and behindit. When they pass in front, they are said to be in transit, when they passbehind it, they are said to be in occultation. The event Wednesday night willbe a double transit, with two of Jupiter?s moons transiting across the face ofthe planet, followed by their shadows a few minutes later. The shadows of themoons trail the moons themselves because Jupiter is now past opposition, sothat shadows fall at an angle.

Here is a play-by-play account of tonight?s events. Forconvenience, times are given in Eastern Daylight Time, so you will need toapply a correction if you?re in a different time zone. For example, if you?rein the Pacific Daylight Time zone, subtract three hours from the times givenbelow.

09:24 p.m. ET | Ganymede begins transit across Jupiter. Visible in 125mm telescope. |

09:43 p.m. | Europa begins transit across Jupiter. Will be hard to see after first few minutes. |

10:21 p.m. | Europa?s shadow begins transit across Jupiter. This begins before Ganymede?s shadow transit because Europa is closer to Jupiter. Visible in 90mm telescope. |

10:41 p.m. | Ganymede?s shadow begins transit across Jupiter. Visible in 90mm telescope. |

12:35 a.m. | Europa leaves Jupiter?s disk. |

01:02 a.m. | Ganymede leaves Jupiter?s disk. |

01:12 a.m. | Europa?s shadow leaves Jupiter?s disk. |

02:20 a.m. | Ganymede?s shadow leaves Jupiter?s disk. |

One of the most beautiful sights will come just after 1a.m. ET when the two moons are off Jupiter?s disk, but are still casting theirshadows on the planet; this gives a wonderful three-dimensional effect.

Notice that the transit of Europa takes a lot less time (2h52m) than the transit of Ganymede (3h 38m); that?s because the Ganymede?s orbitis larger and its period longer than those of Europa. Notice also that theshadow transits take longer than the satellite transits themselves because ofthe geometry of a shadow falling obliquely onto a sphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In some ways it?s quite remarkable that the shadows ofJupiter?s satellites are visible in small telescopes; in fact they are amongthe smallest objects (in angular size) that most of us are ever likely toobserve.

Ganymede?s shadow is 1.1 arcseconds in diameter; Europa?sonly 0.6 arcseconds. These diameters are much smaller than the theoreticalresolution of 90mm and 125mm telescopes, so how can this be? It has to do withthe extreme darkness of these shadows in contrast with the bright cloud tops ofJupiter.

Somehow our eyes and brains can spot these tiny black spotsmore readily that we can separate a pair of equally bright stars, the basis fortelescope resolution figures.

? More Night Sky Features from StarryNight Education

Thisarticle was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, theleader in space science curriculum solutions.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.