Moon Water: A Game-Changing Discovery

This story was updated at 3:00 p.m. ET

The discovery of widespread but small amounts water on thesurface of the moon, announced yesterday, stands as one of the most surprisingfindings in planetary science.

Three spacecraft picked up the signatureof water, not just in the frigidpolar craters where it has long been suspected to exist, but all over thelunar surface, which was previously thought to be bone dry.

"Widespread water has been detected on the surface ofthe moon," said planetary geologist Carle Pieters of Brown University in Rhode Island, who led one of the studies detailing the findings.

While the findings, detailed in the Sept. 25 issue of thejournal Science, don't mean there are pools of liquid water sitting on themoon, it does mean that there is ? entirely unexpectedly ? water potentially tiedup or mixed in the minerals that make up the lunar dirt.

"What we're detecting is completely unexpected," Pieterssaid. "The moon continues to surprise us."

The moon dirt would be akin to soil from an arid environmentlike Arizona ? it wouldn't feel wet to the touch, but there's certainly waterbound up in it, Pieters told SPACE.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This discovery may well revolutionize our understanding ofthe nature of the moon's surface, experts say, and it has geologists eager togo back to the moon and dig up some lunar dirt.

?I rank this as a game changer for lunar science,? said University of Colorado astrophysicist Jack Burns, chair of the science committee for theNASA Advisory Council. Burns was not involved in the new findings. ?In my mindthis is possibly the most significant discovery about the moon since the Apolloera.?

Surprising findings

Samples of lunar rocks brought back to Earth by Apolloastronauts had never shown any signs of water, leading scientists to presumethat the moon was bone dry, except for possible pockets of water ice inpermanently shadowed craters at the moon's south pole.

But the new observations, from the NASA-built MoonMineralogy Mapper (M3) on India's Chandrayaan-1 satellite, NASA's Cassinispacecraft and NASA's Deep Impact probe call into question 40 years ofassumptions on the make-up of the lunar surface.

?If it stands, then that really changes our understanding ofthe lunar surface,? said Ray Arvidson, a planetary scientist at Washington University in Saint Louis who also was not involved in the new studies.

"Really, the moon is much more than a gray body inorbit around the Earth," said Rob Green, of NASA's Jet PropulsionLaboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and the project instrument scientist for M3.

All three spacecraft detected the spectral signature ofwater (the wavelengths of light that it reflects) across the lunar surface. Thesignal, or fingerprint of water, was strongest at the lunar poles. The signalalso varied in strength depending on the time of day, with the most robustsignals coming early in the morning and the lowest at midday.

"The entire surface of the moon will be hydrated duringat least part of the lunar day," said Jessica Sunshine, of the University of Maryland and the deputy principal investigator for NASA's Deep Impactextended mission and co-investigator for M3.

The detection from Chandrayaan came first and took the teammembers by surprise; they first thought it was error in the data that wouldhave to be calibrated for. But no matter what errors they accounted for, thesignal still showed up. The data from Cassini and Deep Impact clinched thediscovery.

"The rest is history now. It is completelyconclusive," Pieters, the principal investigator for M3, said.

The signal actually indicates the presence of both watermolecules and hydroxyl ? an oxygen atom and hydrogen atom bondedtogether, or essentially water missing one of its hydrogens. Hydroxyl is morereactive than water. What minerals bear the hydroxyl isn't clear, thoughexamples of hydroxyl-bearing minerals on Earth are the various clays.

How much of each type of molecule exist on the surface can'tbe determined from the data, but suffice it to say the lunar soil couldn't becalled wet.

"Even the driest deserts on the Earth have more waterthan are at the poles and surfaces, as we've presented here, of the moon,"said Jim Green, director of the Planetary Science Division of the ScienceMission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

The exact form that the water takes on the lunar surfaceisn't clear with the data the scientists have, either, though they have severalideas: The water could be mixed in to the lunar surface or could be a part ofaltered minerals present in the lunar dirt.

"We do not know precisely," Pieters said.

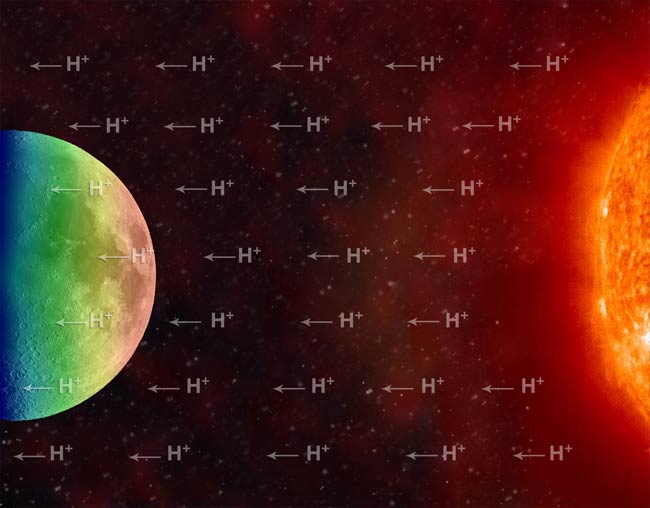

It also remains a mystery how the water and hydroxyl formed,though some of the scientists who made the discovery suggest it could be fromthe interactionof the solar wind with the lunar surface.

Polar water

The findings come just as NASA's LunarReconnaissance Orbiter and LCROSS impactor are set to explore the the lunarsouth pole craters looking for water ice.

"Much to our surprise, we found [water] elsewhere,"Pieters said.

What the new observations are seeing is "water in adifferent mode on the surface altogether," she added, as the polar craterwater ice is thought to be in solid clumps on the surface, while the newlydetected water is attached to surface minerals.

More water could also be stuck underneath the surface asstrong water signals were found in fresh craters, but not in the area aroundthem, suggesting they might have churned up water-rich dirt.

The new findings, though, could help explain how the waterice got to the lunar poles. The fluctuating signals seen throughout the daycould indicate that the water is migrating across the surface toward colder,higher latitudes and eventually the poles.

"If the water molecules are as mobile as we think theyare ? even a fraction of them ? they provide a mechanism for getting water tothose permanently shadowed craters," Pieters said.

When water is heated, it evaporates and moves off thesurface, but gravity can snatch it back down. If the water molecules aren'tswept away by the solar wind or some other force, they could be re-deposited ina different spot. If that spot is colder, they're more likely to stick longer,so slowly, the water would tend to move from warmer to colder spots, in thiscase, the lunar poles.

This type of migration is actually seen on other bodies inthe solar system including Jupiter's moon Ganymede and Saturn's moon Iapetus.

"So we see this kind of migration on other bodies, soit's just a surprise to see it working on the moon," said Roger Clark, ofthe U.S. Geological Survey in Denver and a team member for the Cassinispacecraft and a co-investigator for Chandrayaan-1.

But whether the signals actually show moving water or justwater being created and destroyed daily can't be determined with the current dataand would take a dedicated orbiter to tease apart, Pieters said. There is stilla lot that isn't understood about the interaction between the lunar surface andthe vacuum surrounding it.

"There's a lot of unknowns that we need to workout," Sunshine said.

"We need to go back obviously," Pieters said.

- Video ? Water on the Moon: Hydrogen, Oxygen and Energy

- POLL: Just How Important is Water on the Moon?

- Image Gallery - Full Moon Fever

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.