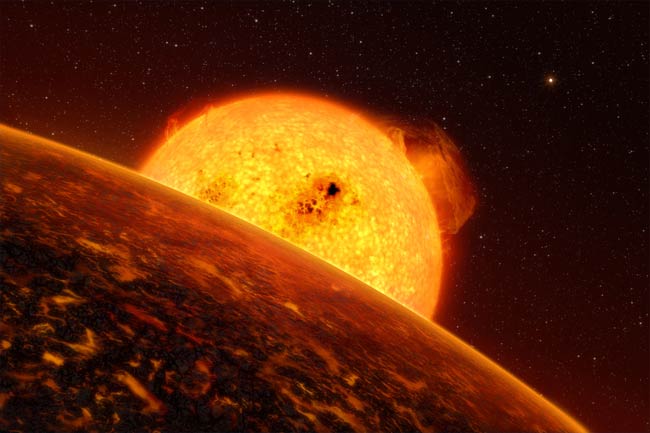

On Alien World, It Rains Rocks

On Earth, strange things, including frogs and fish,sometimes fall from the sky, but on a distant extrasolar planet, the weathercould be even weirder: When a front moves in, small rocks rain down on thesurface, a new study suggests.

The exoplanet,COROT-7b, was discovered in February by the COROT space telescope launched bythe French and European space agencies. Last month it became the first planetoutside our solar system to be confirmedas a rocky body ? most other known exoplanets are gas giants.

The planet is nearly twice the size of Earth and about fivetimes the mass of our world. Calculations have indicated it has a density aboutthat of Earth's, which means it is likely made up of silicate rocks, just asEarth's crust is.

The planet is likely much less hospitable to life though, asit is only about 1.6 million miles (2.6 million km) away from its parent star ?23 times closer than Mercury sits to the sun.

Locked and scorching

Because the planet is so close to the star, it is gravitationallylocked to it in the same way the Moon is locked to Earth. One side of theplanet always faces its star, just as one side of the Moon always faces Earth.

This star-facing side has a temperature of about 4,220degrees Fahrenheit (2,326 degrees Celsius) ? hot enough to vaporize rock.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So unlike the much cooler Earth, COROT-7b has no volatilegases (carbon dioxide, water vapor, nitrogen) in its atmosphere. Instead itsatmosphere consists of what might be called vaporized rock.

"The only atmosphere this object has is produced fromvapor arising from hot molten silicates in a lava lake or lava ocean," saidBruce Fegley Jr., of Washington University in St. Louis.

Rocky weather forecast

To find out what COROT-7b's atmosphere might be like, Fegleyand his colleagues modeled it. They found that COROT-7b's atmosphere is made upof the ingredients of rocks and when "a front moves in," pebblescondense out of the air and rain into lakes of molten lava below.

"Sodium, potassium, silicon monoxide and then oxygen ?either atomic or molecular oxygen ? make up most of the atmosphere,"Fegley said. But there are also smaller amounts of the other elements found insilicate rock, such as magnesium, aluminum, calcium and iron.

The rock rains form similarly to Earth'swatery weather: "As you go higher the atmosphere gets cooler andeventually you get saturated with different types of 'rock' the way you getsaturated with water in the atmosphere of Earth," Fegley explained."But instead of a water cloud forming and then raining water droplets, youget a 'rock cloud' forming and it starts raining out little pebbles ofdifferent types of rock."

Menagerie of minerals

The exoplanet's atmosphere condenses out minerals such asenstatite, corundum, spinel, and wollastonite.

Elemental sodium and potassium, which have very low boilingpoints in comparison with rocks, do not rain out but would instead stay in theatmosphere, where they would form high gas clouds buffeted by the stellar windfrom COROT-7.

These large clouds may be detectable by Earth-basedtelescopes. The sodium, for example, should glow in the orange part of thespectrum, like a giant but very faint sodium vapor streetlamp.

Observers have recently spotted sodium in the atmospheres oftwo other exoplanets.

The new modeling finding is detailed in the Oct. 1 issue ofThe Astrophysical Journal.

- Video ? Planet Hunter

- The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.