Leo's Bright Star Regulus Flies like Bullet

Shining brightly in the constellation Leo is a fast-spinning star that shoots through the cosmos like an extra-wide bullet, perplexing astronomers as it moves through space in the same direction as its polar axis.

Researchers have long known that Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, spins much faster than the Sun, but new observations with an array of telescopes pinned down the star's odd motion and a host of other characteristics.

"We don't have any idea why it's really doing that," said Georgia State University astronomer Hal McAlister, who led the study of the star at the university's Center for High Angular Resolution (CHARA). "The picture makes me wonder what it would be like to be in a solar system with this type of star."

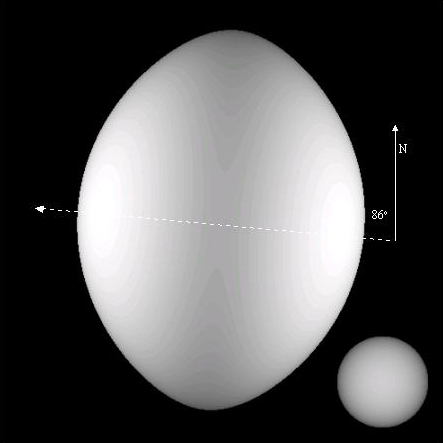

Regulus' axis is tilted about 86 degrees, presenting astronomers on Earth with an askew view of the star.

Using the CHARA array of telescopes atop California's Mount Willson, McAlister and his team were able to make the first observations of how Regulus is shaped by its high-speed rotation: 700,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) an hour spin at its equator.

With such a high rate of rotation -- the Sun, for comparison, has an equatorial spin of about 4,500 miles (7,242 kilometers) an hour -- Regulus bulges out at the center to a diameter about 4.2 times that of Earth's home star. If Regulus spun just 10 percent faster it would rip itself apart, but that's not likely, researchers said.

"There's nothing that we know of that can speed this star up," McAlister told SPACE.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Although Regulus shines about 350 times brighter than the Sun, it burns hotter at its poles (15,100 degrees Celsius) than at the equator (10,000 degrees Celsius), where the pull of gravity is diminished by the star's distorted shape which in turn lowers the temperature, researchers said, adding that the poles shine five times brighter than the equator.

Researchers used measurements of the CHARA array's six telescopes to determine Regulus' temperature, speed spin axis orientation along with a light-combining method called interferometry.

McAlister said that the Regulus study is just the start of observations with the CHARA array.

"Literally we have thousands of other targets to choose from for future study," he said, adding after studying the young, hot Regulus, he'd like to measure the diameters of cooler, older stars. "We're only beginning to dip our toes in this ocean."

This article is part of SPACE.com's weekly Mystery Monday series.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.