Controversial New Idea Surfaces on Origin of Moon's Water

Many experts were shocked by the recent discovery of wateron the moon, which was long thought to be bone-dry.

But not everyone wassurprised.

Astrophysicist Arlin Crotts of Columbia University has beenworking for years on research that he says predicted this finding. In a paperhe submitted recently to the Astrophysical Journal with his graduate studentCameron Hummels, Crotts hypothesizes the existence of widespread water on thelunar surface, and offers an idea for how it got there.

"I am predicting something that just happened, thatnobody else was predicting," Crotts said. "I hope people recognizethat this is a true prediction of the spatial distribution of water around themoon."

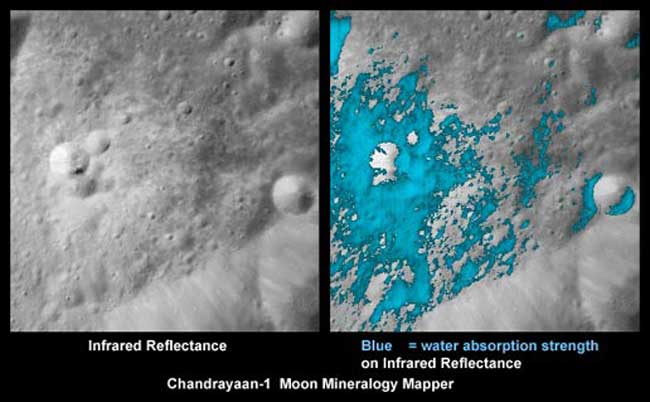

Until recently, many scientists thought the lunar surfacewas almost completely dry, and that shadowedcraters near the poles offered the only chance for small stores of water.But newdata from the NASA-built Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) on India'sChandrayaan-1 satellite, NASA's Cassini spacecraft and NASA's Deep Impact probeuncovered tantalizing evidence of water molecules all over the moon's surface.These findings were detailed in three papers in the Sept. 25 issue of thejournal Science.

Some more details, especially about the possible water atthe poles, are likely to come when NASA'sLCROSS impactor slams into a crater on the moon's south pole Friday morningin search of signs of water.

Where did it come from?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The experts behind the new findings said they don't yet knowthe sourceof this water. According to one hypothesis, charged hydrogen ions carriedfrom the sun to the moon by the solar wind could combine with oxygen on themoon to form water molecules. Another idea is that the water is left over fromcomets that have impacted the moon.

"There are many models out there," said RogerClark of the U.S. Geological Survey in Denver, who is a team member for theCassini spacecraft and a co-investigator for Chandrayaan-1. "Probably tosome degree they all are in play. It's too early to tell."

But Crotts has a different idea in mind.

Previous research has uncovered some water trapped inminerals deep inside the moon, Crotts said. According to his model, this wateris likely to travel up through fissures to the lunar surface along with othergases that are escaping the pressure of the moon?s dense interior.

"We now know that there's water in the interior,"Crotts told SPACE.com. "There's no particular reason to think that itdoesn?t get out."

Buried water

One piece of evidence for interior water - a 2008 Naturestudy by Brown University's Alberto Saal and colleagues - identified water(between 260 and 745 parts per million, or ppm) in pebbles of hardened moonlava brought back by Apollo astronauts. Other work on similar samples byFrancis McCubbin of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington D.C.also indicates the moon could harbor water beneath its surface.

While Crotts thinks those amounts are enough to produce theobserved surface water, other experts are skeptical.

"I feel that it is highly unlikely that there aresignificant amounts of water remaining in the moon's interior at thistime," said Darby Dyar of Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, who wasa co-author on the recent Science papers announcing the surface waterdiscovery. "The amounts of water found are at the parts per million level,and as such constitute only a very small amount of water as a resource."

Other scientists echo this thinking.

"The moon interior is believed to be very dry, withless water than what we observed on the surface," Olivier Groussin, ascientist at the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille in France and anotherco-author on the Science papers, wrote in an e-mail. "Apollo samplesindicate less than 50 ppm of water in the interior, while we detected about1000 ppm on the surface."

Wet moon

However, Denton Ebel, curator of meteorites at the AmericanMuseum of Natural History in New York, said the trace amounts of interior moonwater so far identified could be enough to produce the signature found at thesurface.

"I think the amounts of water that are inferred for thelunar interior from the work of Alberto Saal and the work of Francis McCubbin,coupled with what we know about the lunar core, implies that degassing is aviable cause of the hydrogen signal that?s observed," Ebel said in a phoneinterview.

"I think that [Crotts'] scenario of seepage - slowdegassing - is consistent with the findings," Ebel said. "And I thinkit's more encouraging than the idea of hydrogen implantation by the solar wind.The bottom line is, he could turn out to be right."

Crott's paper outlining his hypothesis has been submitted toan academic journal, and is in the process of being peer-reviewed beforepossible publication. Some scientists are waiting to reserve judgment untilthen.

"I am delighted that scientists have been thinkingalong these lines, but we must wait to see if it holds up to the test of peerreview," said Jim Green, director of the Planetary Science Division of theScience Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., anotherco-author on the Science papers.

To get to the bottom of the issue, more data will be needed,scientists say.

In fact, the signature of water seen on the surface couldeasily result from a combination of multiple processes, Crotts said, adding thathis explanation might only account for some of the water on the surface.

To find out for sure, more lunar expeditions will berequired, Crotts said.

'"We've got to have another polar orbiter mission, andit's got to have some instruments on it that study this question," hesaid.

- Video ? Water on the Moon: Hydrogen, Oxygen and Energy

- Slam-Bang Coverage! Get Ready for the LCROSS Moon Crash

- Images: Full Moon Fever

?

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.