Mars Caves Might Protect Microbes (or Astronauts)

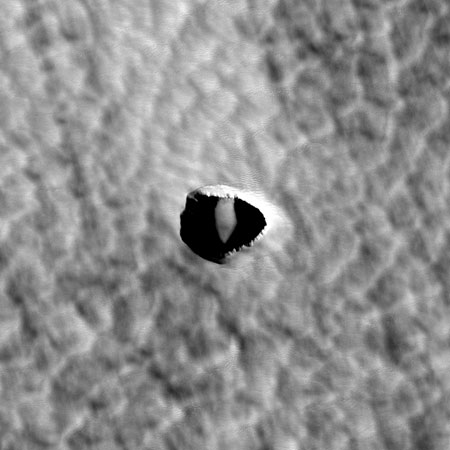

A series of newly discovered depressions on the Martiansurface could be the entrances to a cave system on the red planet.

Hints of subsurface tunnels have been found in images ofMars before, but the new evidence is more suggestive, said Glen Cushing, aphysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey who discovered the possible caves.

Such a subsurface system could provide shelter to futureMars-visiting astronauts, as well as a protective habitat to any potentialpast or present Martian microbes, Cushing said.

Cushing presented his findings recently at a meeting of the GeologicalSociety of America.

Lava tubes and skylights

Cushing found signs of a series of "collapse depressions"in extinct lava flows from the Martian volcano Arsia Mons in high-resolutionimages taken by spacecraft orbiting the red planet.

The depressions appear to be a set of long grooves in thesurface with distinct features that look like skylight entrances intotunnel-like structures. The grooves are more than 62 miles (100 km) long and upto 330 feet (100 meters) across; the apparent skylights look to be up to 160 to200 feet (50 to 60 m) across.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cushing said that the grooves likely formed when a solidceiling of cooled material formed over a lava channel during an ancienteruption. When the eruption was over, a tunnel, or "lava tube," wasleft behind. Sections of the ceiling likely collapsed at some point to form theskylight entrances.

These cave-suggesting features are different than a seriesof seven dark spots ? dubbed "theseven sisters" ? found in 2007 and also thought to potentially be theentrances to a cave system.

"What's special about these [newfound features] is thatthey are closer to the surface and smaller," Cushing told SPACE.com.

Having these smaller tunnels closer to the surface wouldmake them easier to explore and possibly use in future human missions, headded.

Shelter for life

If the depressions turn out to indeed be the entrances tocave systems, they could be both interesting for any future Mars astronauts toexplore and provide asafe shelter.

"Caves can protect human explorers from a range ofdangerous conditions that exist on Mars' surface," Cushing said. "Ifcaves are not used for long-term human habitation, then explorers must eithertransport substantial shelters of their own or build them on site."

The caves also have the potential for holding signsof microbial life, for much the same reason that they would be good shelterfor humans.

"There's numerous hazards on Mars' surface," forstruggling life, including radiation, extreme temperatures and dust storms,Cushing said. "Caves really protect from all of these things."

For these same reasons, caves are more likely to preserveany evidence of past life. "Caves are probably among the only places onMars where you can actually look and see if there's possible evidence" ofpast life, Cushing said.

While the rovers currently on the surface of Mars are toofar away to try to get an up-close look at these possible caves, Cushing thinksthey will be an obvious destination for future missions.

"Someday robot explorers will probably visit caves suchas these and show us a whole new hidden world," Cushing said.

- Video ? Mars Life?

- Video ? Life on Mars: The Search Continues

- Mars Madness: A Multimedia Adventure!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.