Odds Slim for Resurrecting Defunct Mars Lander

Today, NASA will begin attempts to re-establish contact withthe long-defunct Phoenix Mars Lander, which has been enveloped in the frost ofthe northern Martian winter for more than a year now. But chances are slim theprobe will phone home.

The agency's Mars Odyssey orbiter willlisten for any radio signals from the frozen spacecraft on the surface thatwould indicate it survived the months-long deep freeze, though missionscientists aren't optimistic about the odds.

"It is very unlikely that Phoenix has survived the coldwinter, but it is worth the chance to try," Peter Smith, Phoenix principalinvestigator, told SPACE.com.

Phoenix, which landed on the surface of the red planet onMay 25, 2008, has been out of commission since November 2008, when theplummeting temperatures and accumulating frost in the Martian arctic took thespacecraft offline.

The Phoenix mission lasted for two months longer than itsoriginal three-monthmission and confirmed the presence of water ice under the surface of theplanet, which has helped characterize the planet's past potentialfor habitability.

The $475 million lander's hardware was not designed tosurvive the temperature extremes and ice-coating load of an arctic Martianwinter.

On Mars, as on Earth, the sun is lower in the sky in thewinter. For Phoenix, this meant dwindling supplies of energy for its solarpanels during the final days of its mission. Eventually that energy ran out,and mission controllers lost contact with the spacecraft.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As winter set in, the lander also gradually became coveredin frost. More ice crystals likely stuck to the lander after it took its lastpictures. But just how buried in ice the lander became isn't known.

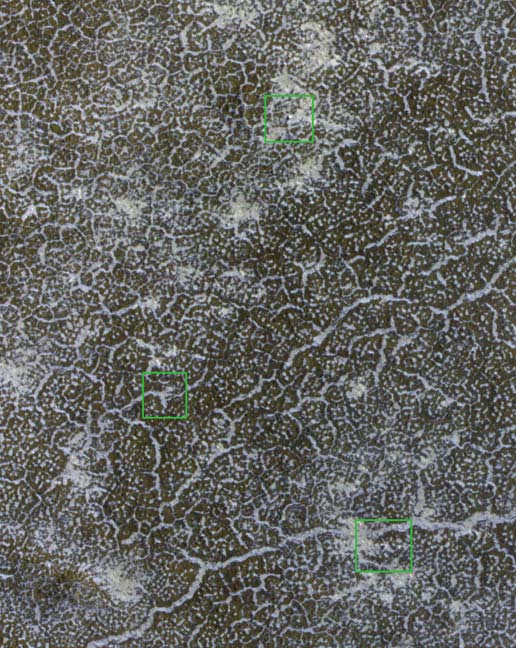

A photograph of Phoenix taken by NASA?s Mars ReconnaissanceOrbiter in orbit on Jan. 6 showed the lander blanketed in carbon dioxide frost.The view, taken as early spring begins on Mars, showed a vast region of frostand bare ground.

Phoenix?s solar arrays are not visible in the new photo,likely because they were still covered in frost, mission managers said.

Phoenix is programmed with a built-in reboot system ? calledits "Lazarus mode" ? that would allow it to try to start itself backup again as soon as its solar arrays had collected enough energy.

But whether the lander will be able to use this mode isuncertain.

The cold temperatures and frost could have caused theelectronics aboard the lander to become brittle and crack. If the electronicswere busted during the winter, it's unlikely that Phoenix will be able to liveup to its name and make a comeback.

When Phoenix went silent more than a year ago, missionmanagers expect never to hear from it again. But they're still going to give ita try and see if Phoenix makes any peeps.

Odyssey will pass over the Phoenixlanding site approximately 10 times each day during three consecutive daysof listening this month and two longer listening campaigns in February andMarch.

During the later attempts in February or March, Odyssey willtransmit radio signals that could potentially be heard by Phoenix, as well aspassively listening.

If Phoenix signals its survival, Odyssey will try to lock onto its signal and see what the lander is capable of doing. NASA will base anyfurther decisions on the lander on that information.

- Video? Looking for Life in All the Right Places

- SPECIALREPORT: Highlights of the Phoenix Mars Lander Mission

- Images:Phoenix on Mars

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.