Smacks in the Face Explain Unique Looks of Two Moons

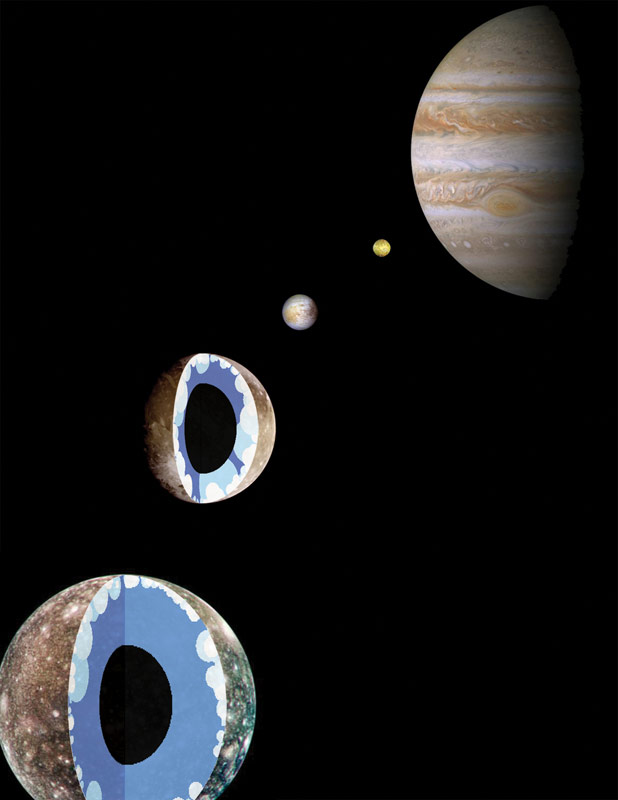

Each of Jupiter's more than 60 moons has its own uniquecharacter, but scientists have often wondered at the striking differencesbetween the surfaces and interiors of two of the gas giant's largest moons,Ganymede and Callisto.

A new study, detailed in the Jan. 24 issue of the journalNature Geoscience, might have found an explanationfor the disparate features of these Galilean moons: Ganymedewas pummeled by more and faster comets impacts than its sister moon billions ofyears ago.

While Ganymede and Callisto aresimilar in size and both made up of a mixture of ice and rock, data from boththe Galileo and Voyagermissions show that they sport different looks, both on the inside and outside.

But just why the two moons looked so different is a problemthat planetary scientists have been grappling with for 30 years. The solutionto the problem could shed light on how our solar system, and planets ingeneral, evolved.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Similar to Earth and Venus, Ganymede and Callisto are twins, and understanding how they were bornthe same and grew up to be so different is of tremendous interest to planetaryscientists," said Amy Barr of the Southwest Research Institute PlanetaryScience Directorate.

Ganymede has a surface that shows evidence of resurfacing bytectonic processes ? the same forces that continually reshape the surface ofthe Earth. The moon also has a large rock/metal core, showing that itsconstituent materials separated out over time, with the heavier stuff settlingto the interior of the planet (just as the iron present in Earth settled to thecore, while the lighter rocky materials floated to the surface).

The surface of Callisto, on theother hand, shows no signs of resurfacing, and the separation of rock and icewithin it seems to be incomplete.

Barr and her colleague Robin Canupcreated a model that looked at the possible role of comet impacts in theevolution of these two moons. The model simulated the impacts and rocky coreformation and found that Ganymede and Callisto'sevolutionary paths diverged around 3.8 billion years ago, during a period inthe solar system's life called the LateHeavy Bombardment. (The pockmarked surface of Earth's moon shows that thisperiod was dominated by large impacts).

In the model, Jupiter's strong gravity focusescomets that swing into the neighborhood into the paths of Ganymede and Callisto.

When a comet impacted either moon, the mixed ice and rockthat made up the surface would have created a pool of liquid water, allowingrock in the melt pool to sink to the moon's center.

Because Ganymede is closer to Jupiter, it was hit by twicethe number of impactors as Callistowas. The proximity to Jupiter also meant that the comets colliding withGanymede were going faster than those that hit Callisto.

The model shows that if the impacts to Ganymede releasedenough energy, the process of rock sinking and core formation could have becomeself-sustaining.

"Impacts during this periodmelted Ganymede so thoroughly and deeply that the heat could not be quicklyremoved. All ofGanymede's rock sank to its center the same way that all the chocolate chipssink to the bottom of a melted carton of ice cream," Barr said. "Callisto received fewer impacts at lower velocities andavoided complete melting."

These model findings help link the evolution of Jupiter'smoons to the overall evolution of the solar system and the history ofbombardment of Earth's own moon.

- Video ? Return to Jupiter

- New Map Reveals Geology of Jupiter's Moon Ganymede

- Images: Jupiter's Moons

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.