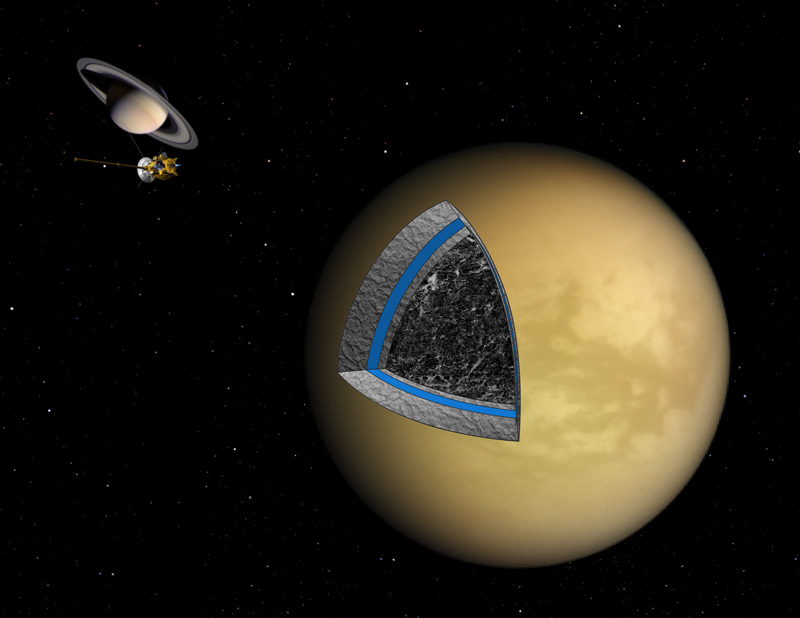

Saturn's Moon Titan Is Slushy Inside

The insides of Saturn?s largest moon Titanare arranged like a slushy mix of rock and ice instead of the rigidly layeredstructures found in other bodies across the solar system, NASA's Cassinispacecraft has found.

Astronomers were able to determine thetemperature and consistency of Titan's slushy innards by measuring thegravitational tugs registered by Cassini as it flew by the cloudy Saturnmoon.

"There have been several flybys of Titanby Cassini," said study co-author David Stevenson, a professor ofplanetary science at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif."As it goes by, its path is deflected by thegravity of Titan. We use that deflection to learn about the gravity ofTitan."

The gravity data reveals that the first 300miles (500 km) down into Titanis devoid of any rock fragments, while ice and rock are mixed to variousextents at greater depths. Cassini was able to record the data during fourflybys of Titan between February 2006 and July 2008.

Scientists have long-known that Titan is madeup of about equal parts rock and ice. Cassini's gravity data confirmedthat finding and also revealed new details on the exact consistency anddistribution of the interior material's makeup.

Cassini researchers described Titan'sinterior as "a sorbet of ice studded with rocks," in a recent NASAstatement.

Researchers think Titan never heatedup beyond a relatively lukewarm temperature, which explains why the moon's iceand rock have not fully divided and formed layers within Titan's interior likeother bodies in the solar system.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"To avoid separating the ice and therock, you must avoid heating the ice too much," Stevenson told SPACE.com."This means that Titan was built rather slowly for a moon, in perhapsaround a million years or so, back soon after the formation of the solarsystem."

Cassini built the gravity map of Titan byflying about 800 to 1,200 miles (1,300 to 1,900 km) above the moon. Scientiststhen used ground-based antennas with the Deep Space Network to note changeswithin five thousandths of a millimeter per second in the Cassini's speed asTitan's gravity perturbed the spacecraft path along its orbit.

"These results are fundamental to understandingthe history of moons of the outer solar system," said Cassini project scientistBob Pappalardo at JPL. "We can now betterunderstand Titan's place among the range of icy satellites in our solarsystem."

Cassinihas been studying Saturn and its rings and moons since 2004, when it arrived inorbit around the gas giant planet. The spacecraft completed its initial missionin 2008 and received and extended flight through 2017 earlier this year.

- Images- The Rings and Moons of Saturn

- Cassini'sGreatest Hits at Saturn

- Mysteryof Saturn's Rings May Finally Get Answer

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.