Astrobiology Field Reports: Are Canadian Lake Structures Biological or Chemical?

A team of scientists and astronauts is sent an expedition to Canada's Pavilion Lake this summer to study the lake's odd bacterial life and practice techniques that may one day be used to seek out life on other worlds. Here, Astrobiology Magazine's Henry Bortman sends the latest field report from the project:

July 3, 2010

The Big Question at Pavilion Lake is this: What role does biology play in forming the microbialites found here? The undisputed fact is that the microbialites are covered in living bacteria. What's less clear is whether the bacteria influence the formation of the lake's carbonate structures or the microbialites form though some purely chemical process, with the bacteria merely hanging out in the neighborhood.

As Curtis Suttle of the University of British Columbia pointed out, "There are certain microbes that might like to live in high-carbonate environments, that just happen to grow there, not because they made them but because it's an environment they like to live in."

Of course, most people, myself included, is secretly rooting for biology. Otherwise Pavilion Lake's microbialites won't be much help in the search for signs of life on other worlds, except as an indicator of what not to look for. But scientists aren't supposed to play favorites. Which is why the researchers I spent time with today are going to what you might call extreme lengths to answer The Big Question.

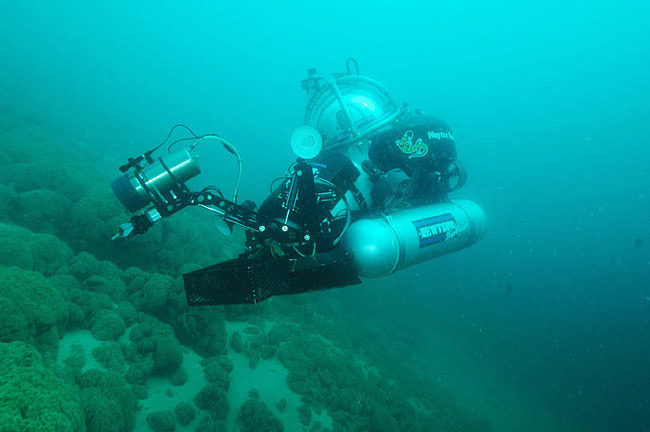

DeepWorker submarine pilots had just brought back some 100 liters (about 26 gallons) of lake water when I arrived at Suttle's outdoor lab. Suttle is the principal investigator for MARS LIFE (Mars Analogue Research: Signatures of Life in Freshwater Environments), a project funded by the Canadian Space Agency. His group is conducting DNA analysis of what's living on the Pavilion Lake microbialites and in the water around it. Not the big stuff, like worms and shrimp. They're interested in bacteria and archaea. And viruses.

Suttle's team is looking at multiple samples, obtained by scuba divers and DeepWorker pilots from several different depths. Their primary interest is in finding out what communities of organisms inhabit the various microbialites, whether those communities vary with depth. Their reason for also studying lake water is as a reference point. They want to know which of the organisms living on the microbialites are also present in the water, and which are unique to the microbialites themselves.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Their lab consisted of a slanting cafeteria-type table set up under a square blue canopy; on the table was a maze of beakers and plastic tubing. Suttle and some of his grad students and post-docs were pumping the water through a series of filters, the final stage of which was so fine that only viruses got trapped in it.

A typical virus is tiny, about 1/1500th the width of a human hair. Earlier stages in the filtering process had gotten rid of all those pesky multi-celled organisms, leaving behind only bacteria.

The trapped material was then carried to a second makeshift lab, in a basement about a quarter of a mile away, where DNA was extracted, purified and concentrated with state-of-the-art technology to produce a critical mass for later genetic sequencing. "We have taken an instrument into the field that is able to measure nucleic acids at very low levels, and our goal was to see if we could actually detect DNA in just a little water sample," Suttle said. He clarified that "just a little water" meant 2 microliters. That's 1/2500th of a teaspoon. He's hoping to be able to "detect a single molecule of DNA in lake water."

Overkill? Not according to Amy Chan, a research scientist in Suttle's group. "You're not going to get a huge amount [of sample] on a mission" to, say, Mars. "We want to know what is the smallest sample size you can get that will give you something you can detect." One molecule's pretty close to the limit, I'd say.

The equipment Suttle's team was using is not the kind that usually gets set up in basements or on rickety cafeteria tables.

As Richard White, a Ph.D. student who works with Suttle, told me, "Most people in labs would go out of their minds" working under such conditions. But as Danielle Winget, a post-doc in Suttle's group, explained, they wanted to be as close to the source of the genetic material as possible, to avoid both contamination of the samples and degradation of the DNA, degradation that can begin as soon as it's removed from its natural environment. Even setting up on land was a compromise, Winget said. "We would rather have put our lab on a boat."

Okay, cool, you may be thinking. Advanced DNA work done in the field. But why viruses? Surely no-one thinks viruses are building the Pavilion Lake microbialites.

"Viruses amplify life," Suttle says. "For every living organism that you find, there's many, many more viruses that infect that organism." On average, there are a million bacteria in a milliliter of water. And 10 million viruses.

What's more, although the genome of an individual virus is relatively small, "Collectively, viruses probably have about 90 percent more genetic information than we find in the three domains of life" combined, Suttle says. Let's go over that again: 90 percent of the genes found in viruses are not found in cellular organisms.

For example, "Other lifeforms only have double-stranded DNA. Viruses have double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, positive-sense single-stranded RNA, negative-sense single-stranded RNA, double-stranded RNA. They have every possible combination of nucleic acids for passing along genetic information." They're quite versatile.

So if you want to look for life on another world, you'd do well to learn how to hunt for viruses, Suttle suggests. "They're like a biosignature for other living organisms."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Henry Bortman was the managing editor of Astrobiology Magazine, a NASA-sponsored website. He began his career in journalism at the Berkeley Tribe in the early 1970s and wrote for MacUser magazine until it merged with Macworld in 1997 before transitioning to science writing. He is also an avid outdoorsman, enjoying hiking, backpacking, rafting and kayaking.