Predicting Space Weather Needs International Response

Thesun's erratic and sometimes volatile behavior has the potential tocause realproblems here on Earth, and protecting our planet will require aninternationaleffort, according to scientists who gathered recently for a meetingabout theeffects of solar activity.

Streamsof charged particles that fly off the sun can interfere withelectronics onEarth and satellites orbiting our planet. For example, during aparticularlyintense solar storm in 1989, power to an entire Canadian province wasknockedout. Since then, other storms have knocked a handful of satellites outofservice.

WithEarth becoming more and more dependent on technology, the risk fromsolarflares is only going up, experts say.

Facingthe risks

Representativesfrom more than 25 of the world's most technologically-advanced nationsconvenedlast week for the International Living with a Star (ILWS) meeting inBremen, Germany,to discuss the importance of developing better methods for forecasting space weather.

"Theproblem is solar storms" ? figuring out how to predict them andstaysafe fromtheir effects," said ILWS chairperson Lika Guhathakurta from NASA'sHeadquartersin Washington, D.C. "We need to make progress on this before the nextsolar maximum arrives around 2013."

Bythen, solar storms will be at their strongest and most frequent in theroughly11-year cycle of the sun's activity, which is just now emerging from anunusually long period of quiescence.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Thesun's constant interaction with Earth makes it imperative for solarphysiciststo keep track of solar activity.

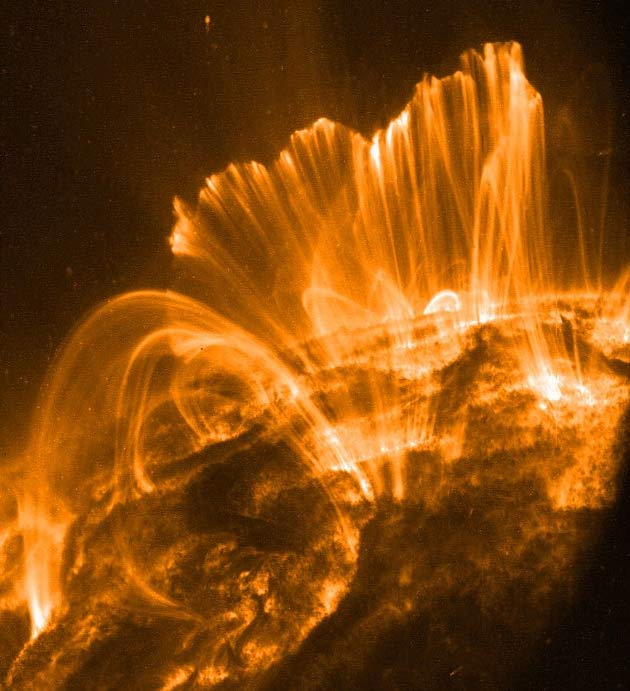

Thesun and Earth are separated by 93 million miles (150 million km), whichis notas great a distance in space as it may sound. Spacecraft andground-basedobservations have determined that Earth is actually located within thesun'souter atmosphere, where it is constantly being battered by solar winds and hail storms ofenergeticparticles.

Infact, the sun and Earth are actually connected by invisible threads ofmagnetism. During so-called "reconnection events," invisible lines offorce can be traced all the way from Earth's poles to the surface ofthe sun.These events typically happen several times a day.

"TheEarth and sun are interconnected," Guhathakurta said. "We cannotstudy them separately anymore."

Aleague of its own

Theterm "heliophysics"is used to describe the science of the sun-Earth system, and the fieldof studyhas expanded significantly in the past few years. NASA has a dedicatedHeliophysics Division at the agency's headquarters, and the UnitedNationsdeclared 2007 the "International Heliophysical Year" in hopes ofstimulating global involvement.

But,predicting solar activity is an extremely complicated task, and beingable toforecast the sun's behavior solves only half of the equation.

Equallyimportant is being able to understand how the Earth's magnetic fieldandatmosphere respond to any given solar storm, scientists said. So far,this hasremained a mystery to top researchers, even with the aid of the mostpowerfulsupercomputers. As a result, the ability to track and monitor spaceweather hasseverely lagged behind the science of Earth weather.

"Weneed more data ? and more ideas," Guhathakurta said.

Aninternational effort

Thisweek, Guhathakurta will hand over her chairmanship of ILWS to Ji Wu oftheChinese Academy of Sciences. Wu will also spend the next two yearscultivatingthe talents of Chinese heliophysicists.

"Wehave many scientists and lots of fresh ideas," Wu said. "China willbe able to make important contributions in this area."

Yetanother challenge is the ability to study heliophysics as it plays outacrosshundreds of millions of miles. NASA and other space agencies havedeployeddozens of spacecraft, but they are spread out over an enormousdistance.

"Imaginetrying to monitor Earth's oceans with a small number of buoys,"Guhathakurta said. "You'd miss a lot. That's the situation we're in nowwith the 'ocean of space.'"

Chinais preparing to launch a space buoy, known as "KuaFu," which will belocated at the L1 Lagrange point - a spot where the Earth'sand sun's gravity balanceout, allowing a satellite to perch there continuously. The probe, whichwillsample the solar wind upstream from Earth, is named after a giant inChinese mythologywho wished to capture the sun.

"We'reputting KuaFu at a strategic point in space," Wu said. "The solarwind at L1 is an important input to many science models of thesun-Earthinteraction."

KuaFuwill join a growing international fleet of spacecraft that arededicated toheliophysics. NASA, the European Space Agency, the Russian FederalSpaceAgency, the Canadian Space Agency, and the Japanese AerospaceExploration Agencyhave also made significant contributions to the field.

Justin time?

Still,mobilizing an increased international effort could be more importantnow thanever before, scientists said. If current forecasts are correct, thesolar cycleis expected to peak during the years around 2013. While it likely won'tbe thebiggest peak on record, human society is becoming increasingly morevulnerable.

Therituals of daily life ? from communications to weather forecasting tofinancialservices ? are highly dependent on satellites and electronics. A 2008report bythe National Academy of Sciences warned that a century-class solar storm could cause billions of dollars ineconomic damage.

Scientistsat the ILWS meeting are hoping to address concerns of such a "solarKatrina" situation, while also determining the best ways to launch newscience and harness the talents of heliophysicists around the globe.

- Images: Hyperactive Sun

- Video ? How Space Storms WreakHavoc on Earth

- Sun's StrangeBehavior BafflesAstronomers

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.