Claims of 100 Earth-Like Planets Not True

Despite overzealous news headlines this week, NASA's Keplerspacecraft has not indentified more than 100 Earth-like planets in the galaxy.

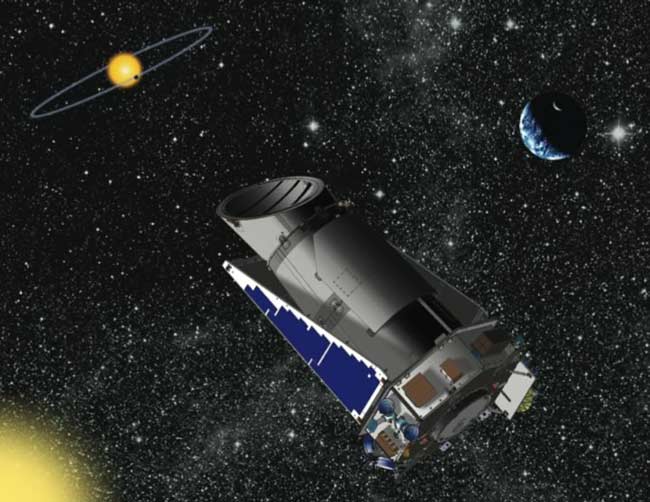

The planet-huntingtelescope, launched in April 2009, has so far confirmed only five alienplanets beyond the solar system, mission scientists told SPACE.com.

The erroneous reports of new planets were generated inresponse to a recent videotaped speech Kepler co-investigator Dimitar Sasselovgave at a TED (Technology Entertainment and Design) conference in July.

"More than 100 'Earth-like' planets discovered in pastfew weeks," read the headline of a Wednesday article in the U.K.'s DailyMail newspaper. The Observer, another U.K. paper, also reported the finding.

However, Sasselov was referencing only possible planetsamong the Kepler data, scientists said.

"What Dimitar presented was 'candidates,'" said DavidKoch, the mission's deputy principal investigator at NASA's Ames Research Centerin Moffett Field, Calif. "These have the apparent signature we arelooking for, but then we must perform extensive follow-up observations toeliminate false positives, such as background eclipsing binaries. This requiressubstantial amounts of ground-based observing which is done primarily in thesummer observing season."

In June the Kepler team announced the discovery of 706planet candidates ? objects that preliminarily have the right signature tobe alien worlds.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The telescope looks for stars whose light appears to dimperiodically, representing the time when a planet passes in front of the starand temporarily blocks some of its light. These findings were detailed in ascientific paper by Kepler's science principal investigator William Borucki,also of NASA Ames.

"In my TED talk I was simply repeating what was alreadyannounced by the Kepler team back [on] June 15, 2010 and is in the Borucki etal., paper," Sasselov told SPACE.com.

"So, no new news here ? but more to come later in theyear!" he said.

Koch confirmed that Kepler's official planet tally is stillmuch lower. "Other than the 5 planets previously published, we have notannounced anything else," he said.

However, Sasselov did say that what Kepler has learned sofar about extrasolar planets offers tantalizing hints that our planet may notbe unusual.

Among the hundreds of candidate planets, a large percentageof them appear to be Earth-like ? that is, small and rocky, rather than largeand gassy, like Jupiter.

"Even before we have confirmed the planets among thesehundreds of candidates, we can see statistically that the smaller-sized planetswill be more common than the large-sized (Jupiter- and Saturn-like ones) in thesample," Sasselov explained.

That's good news for scientists who hope to one day detectlife on another planet. Since life as we know it is thought to require waterand Earth-like conditions, planets that look a lot like ours could behabitable.

To date, using a variety of methods, astronomers haveconfirmed almost 500 planets beyond our solar system, Sasselov said. So far,most of these definitive planet finds have been of the gas giant variety, butthat's because they're easier to spot than planets like Earth. [Thestrangest alien planets]

As telescopes and planet-huntingtechniques improve, and as researchers follow-up on Kepler's observations,the tally for siblings to Earth should go up, he said.

- Gallery - Strangest Alien Planets

- Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts

- Color-Changing Planets Could Hold Clues to Alien Life

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.