Young Stars Blamed for Space Cloud Ripples

Young,massive stars have been caught setting off ripples through a giant space cloud inthe same way that wind drives waves on the ocean.

Theintermittent ripples were seen in a molecular cloud associated with the Orion nebula,a well-known stellar nursery within the constellation Orion.

Anew study led by Olivier Bern? of Leiden University in the Netherlands foundthat intense radiation emitted by nearby stars more massive than our sun was atthe root of the process. The research is detailed in the Aug. 19 issue of thejournal Nature.

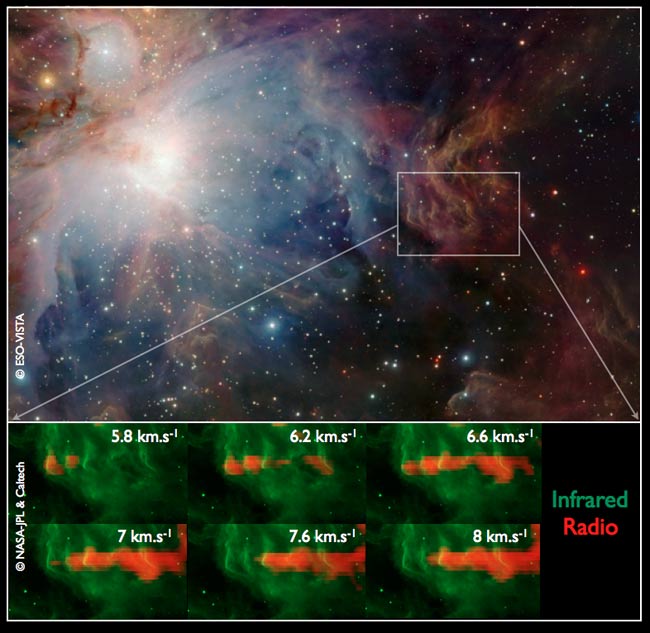

Bern?and his colleagues think the ripples are a signature of the high-velocity "wind"from the stars that once blew across the cloud surface. [Image of the massive stars and rippling cloud]

"Wethink it happened less than 1 million years ago, which is somewhat recent inastronomical scales," Bern? told SPACE.com.

Massivestars make their mark

TheOrion cloud's young, massive stars emit radiation that interacts with the surrounding molecular gas anddust in their birth-cloud. Astronomers had thought this interaction could compressor fragment the cloud, but until now, there had been no clear evidence of suchoccurrences.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Bern?and his colleagues observed the ripples at the surface of the Orion cloud and determinedthat the process is similar to a familiar one on Earth.

"Insimple terms, it is the same type of ripples that you can see at the surface ofthe ocean when the wind is blowing over the water," Bern? said. "Sowhat we think is happening is that the massive stars that are nearby, they blowwinds of ionized gas, and this wind is running over the interstellar clouds andmaking these ripples in a similar way."

When massivestars form, they produce very energetic ultraviolet light, Bern? explained. Thislight heats the surrounding gas to temperatures of over 1,800 degreesFahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius). Scientists call the cosmic ripple effect theKelvin?Helmholtz instability.

Studyingthe ripples

The ripplingeffect, said Bern?, can best be understood by comparing it to processes seen onEarth.

"Theripples on the ocean occur when you have two fluids and a difference invelocity between these fluids," Bern? said. "This produces theinstability. You can see it on the ocean, and you can see it in the atmosphereat the surface of clouds. When clouds in the sky get ripples, it is because ofthis same mechanism of instability."

Bern? andhis colleagues combined data from two different telescopes to make theirobservations. Using NASA's infrared Spitzer Space Telescope, the researchers traced the surfaceof the Orion molecular cloud, where the dust is heated to very hightemperatures.

These datawere combined with findings from a second radio telescope, which probed theinside of the cloud, where the gas is very cold. In some regions, temperaturesdip to below minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit. (minus 200 degrees C.).

What thistells us

Theresults of the study will help researchers understand more about the feedbackthat massive stars have on their surrounding environment.

"Itallows us to understand the turbulent nature of the interstellar medium," Bern? said. "This is important when wewant to understand how new stars can then form from these interstellarclouds."

Therippling effect also will help researchers better understand interstellarchemistry and some of the detailed processes that shape the interstellarmedium. In particular, the ripples in the Orion molecular cloud act as relicsof past activity in the region, helping to shed light on its history.

"Wecan see these ripples as a footprint of past activity of the massivestars," Bern? said. "This is useful to understand what happened inthe past in this region."

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Images ? Constellations of the Stars

- Spectacular Nebulas in Deep Space

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.