Moon's Face Reveals Extreme Cosmic Abuse

The moon's pimpled face is a testament to the seriousbeating it's received over the years from incoming space rocks, and a new studyhas found just how severe that lunar smackdown has been.

Scientists have compiled the first comprehensive catalog oflarge craterson the moon to document its cosmic abuse. They've also made a detailedstudy of minerals on the moon and identified areas of unusual silica-richcomposition, in a pair of related studies.

"For the first time we're actually detecting howcomplex the lunar surface is," said planetary scientist Benjamin T.Greenhagen of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., leader ofone of the mineralogy studies. "It's a bit of a paradigm shift." [Seethe new moon map]

The new findings are detailed in threepapers in the Sept. 16issue of the journal Science.

Mapping the holes

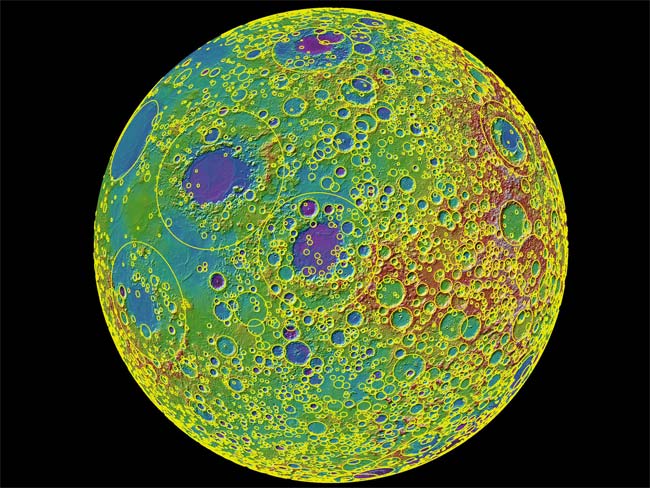

In a second study, scientists built a new lunar crater mapwith data from the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter instrument on NASA's LunarReconnaissance Orbiter,which includes 5,185 craters that are 12 miles (20 km)in diameter or larger.

The database provides a window on the past, revealing whichparts of the moon are mostpockmarked, and therefore represent older surfaces, and which areas havebeen covered over with fresh material by volcanism relatively recently. Theresearchers discovered that the moon's oldest regions are the southern nearside and the north-central far side.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One feature, the South Pole-Aitken basin, appears to be the oldestbasin on the moon. As such, it could offer unique clues about the moon'shistory, and the story of the early solar system in general.

The findings "are telling us something about theinfancy of the solar system," said the study's leader James W. Head III, aplanetary geologist at Brown University, in a statement. "It is clear wecan find out and learn so much more from future missions, robotic or otherwise.There is so much to do."

Rare moon minerals

Researchersused the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment,also on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, to measure the infrared light comingfrom the moon in several frequencies. Long-wavelength infrared light is heatenergy, and it can give researchers information about some of the mineralcontent of the lunar surface not available from visual or other-wavelengthobservations.

In particular, the scientists looked for areas rich insilica (made of the chemical compound silicon dioxide), a type of rock that includes quartz andother formations. This compound is relatively rare on the moon, and requires a particularvolcanic process for creation.

The team found five spots on the moon rich in silica,showing that this mineral does exist on the moon, but is indeed ?rare.

A third team of researchers, led by Timothy D. Glotch of NewYork's Stony BrookUniversity, honed in on some of these spots and found that thesilica on the moon is likely quartz, silicon-rich glass or alkali feldspar.

"Thesilica-rich materials have actually been proposed to be on the surface in theselocations, but we have never sent an instrument that could detect thembefore," Greenhagen told SPACE.com. "It's important to know thesilica-rich regions because they require a very specific type of crustalevolution."

- NASA'sLunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Gets New Moon Mission

- Top 10 Coolest New Moon Discoveries

- The Greatest Moon Crashes Ever

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.