Theicy Comet Hartley 2 put on an interesting show duringan unusually close pass by Earth last month and is poised to be visitedby aNASA space probe on Thursday (Nov. 4). Now, there may be an unexpectedbonus: a new meteor shower.

Thenew meteor shower, which astronomers havebilled the ?Hartley-ids,? could brighten the night skies in earlyNovember,with the peak times occurring between Nov. 1 and Nov. 3. [Photosof Comet Hartley 2]

Infact, some skywatching cameras have revealedtwo fireballs that may be the result of Hartley 2 meteors ?or maybe not. Hereis the story:

Recipefor a meteor shower

Asa comet nears the sun, particles are shed from itsnucleus. Thus its orbit is not an imaginary path through space likeEarth's,but a continuous trail of dust moving in the same direction as thecomet.

Everytime Earth crosses one of these dust trails, itstops millions of orbiting particles, and alert observers might catch aglimpseof some of these plunging through our atmosphere from their location;airfriction vaporizes the particle with a flash of light.

Thismay start at about 80 miles (nearly 129 km) abovethe Earth and end a second or two later at about 40 miles (64 km).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Strictly speaking, the word "meteor" is usedonly for this brief luminous lifetime. When still out in space, theparticlesare called meteoroids.

Ameteor that rivals Jupiter or Venus in brightness is afireball. One that breaks up along its luminous flight across the sky ?oftenwith a strobe-like flash ? is called a bolide. Some are so large thatparts ofthem reach the ground and become geologic specimens called meteorites.

Inthe case of CometHartley 2, the possibility of it spawning a meteor shower arepracticallynil: the orbits of the comet and Earth never intersect or approach eachotherclose enough for that dusty comet material to interact with ouratmosphere.

Butrecently, something took place which made one meteorexpert stop to reconsider the possibility.

Fierycoincidence?

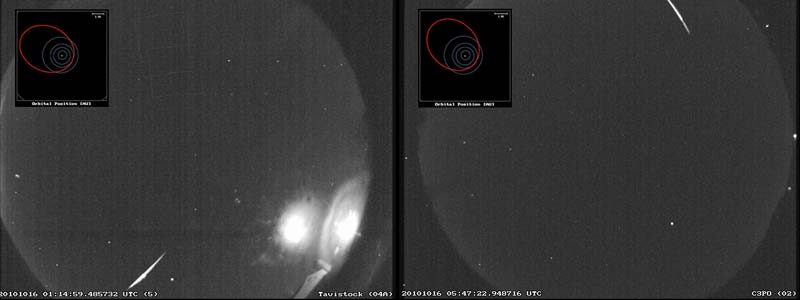

OnOct. 16, a pair of NASAall-sky cameras caught an unusual fireball streaking across the nightsky overAlabama and Georgia. It was bright, slow, and strangely similar toanotherfireball that passed over eastern Canada less than five hours earlier.

TheCanadian fireball wasrecorded by another set of all-sky cameras operated by the UniversityofWestern Ontario. Because the fireballs were recorded by multiplecameras, itwas possible to triangulate their positions and determine their orbits.

Thisled to BillCooke of NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office to make aremarkable conclusion: "The orbits of the two fireballs wereverysimilar. It's as if they came from a common parent."

Asit turned out, the orbitsof the two fireballs were not only similar to one another, but alsoroughlysimilar to the orbit of Comet Hartley 2.

"Itmakes me wonder,"Cooke said, adding that "thousands of meteoroids hit Earth's atmosphereevery night. Some of them are bound to look like ?Hartley-ids? just bypurechance."

Cometcrumbs from space

Sowhile the odds are still long for any kind ofsignificant meteoractivity from Comet Hartley 2, perhaps it is not entirely outof thequestion.

Infact, 13 years ago I had discussed the possibility ofa meteor shower from Hartley 2 on MeteorObs, an Internetforum for meteorobservers.

OnOct. 27, 1997, I posteda message whichindicated that the orbit of the comet was probablytoo far removed from the Earth?s to create any meteors. The two orbitsarecurrently separated by 6.2 million miles (10 millionkm).

Likeother comets, Hartley 2 leaves a dusty trail ofmaterial in its wake. This trail might widen to perhaps a million milesor morein width after it has circled the sun a few times, but in the case ofHartley 2,this still amounts to only a fraction of the present distance betweenthe orbitsof the earth and the comet.

Soat first glance it doesn?t appear that any prospectivemeteor stream from comet Hartley 2 would be wide enough to even reachthe vicinityof Earth.

Whatif there IS a meteor shower?

Let?splay devil?s advocate for a moment and assume anobservable meteor shower from Comet Hartley 2 is a lock.

BecauseHartley 2 is a member of Jupiter's comet family,it periodically passes close enough to that giant planet to have itsorbitperturbed by Jupiter's gravitation. In fact, my own calculations showthat overthe past 40 years, Jupiter has notably altered the orbit of Hartley 2at least threetimes: in Dec. 1993, Dec. 1982 and May 1971.

Andduring the years 1985 and 1991, the distanceseparating the Earth?s orbit from the orbit of the comet was less thanhalfwhat it is now. The dust that was shed by Hartley 2 during those yearslikelyhas orbited the sun three or four times and now just might be passingcloseenough to our orbit to perhapsencounter the Earth and producemeteors.

Asit turns out, Earth is rapidly approaching that partof its orbit where we will be passing closest to the orbit of CometHartley 2.

Wewill, in fact, be nearest on the nights between Nov. 1and Nov. 3. More interestingly, the source of any prospective meteors ?CometHartley 2 itself ? will have passed through this region of space just aweekbefore Earth's own arrival.

Sincethe greatest concentration of dusty materialusually is in the general vicinity of a comet, the Nov. 1 to Nov. 3timeframeoffers skywatchers the best chance of catching a view of a Hartley-idmeteor.

Someobserving tips

Ifyou want to see if there might be any meteor activitythat can be traced back to Comet Hartley 2, here are a fewtips:

First,any meteors belonging to the comet will appear toemanate from out of the constellation of Cygnus, the Swan.

Atthis time of year, Cygnus is almost directly overheadas darkness falls and does not set below the northwest horizon untilaround 3a.m. local time. So, it will be in view for much of the night.

Inaddition, during the key Nov. 1 to Nov. 3 interval,the moon will be a waning crescent and won?t rise until after 3 a.m.localtime. So it will offer no interference.

Also,because Comet Hartley 2 and the Earth are travelingaround the sun in the same direction, any Hartley-id meteor wouldappear tomove very slowly across the sky.

Theirentry speed into our atmosphere would be equal toonly 7 miles per second (11.3 kps); about as slow any meteor can be.Contrastthis to the annual November Leonidmeteor shower, whose particles are moving in a directionopposite to the Earthand hit our atmosphere head-on at 45 miles per second (72.4 kps).

Leonidmeteors usually flash across our line of sight inless than a second, but a Hartley-id meteor may take many seconds topassacross the sky. Such slow meteors often display hues of red or yelloworange incontrast to the white or blue-greens that the Leonids are knownfor.

Andlastly, keep your expectations low.

Don'texpect to step outside and immediately see meteors.Since the Earth may literally be right on the edge of the comet's dusttrail, consideryourself fortunate if you see any Hartley-ids at all.

Infact, Russian astronomer, Mikhail Maslov has made hisown calculations for possible Hartley-id meteors in 2010. He concludedthat "activityis not expected."

NASA?sCooke is also skeptical.

"It'sprobably going to be a non-event," Cookesaid.

Butthen again, as the old saying goes, "nothingventured, nothing gained."

"This sets up nicely,"Cooke added. "Cool weather, waning moon, and the possibilityofseeing a new shower. I will definitely be outobserving if theweather cooperates."

Howabout you?

- Images - The Best of Leonid Meteor Shower

- HowComets Cause Meteor Showers

- SpacePickle? Bowling Pin? Comet Hartley 2 Takes Curious Shape

JoeRao serves as an instructor and guestlecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomyfor TheNew York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camerameteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.