Saturn's second-largest moon Rhea has a wispy atmosphere with lots of oxygen and carbon dioxide, a new study has found.

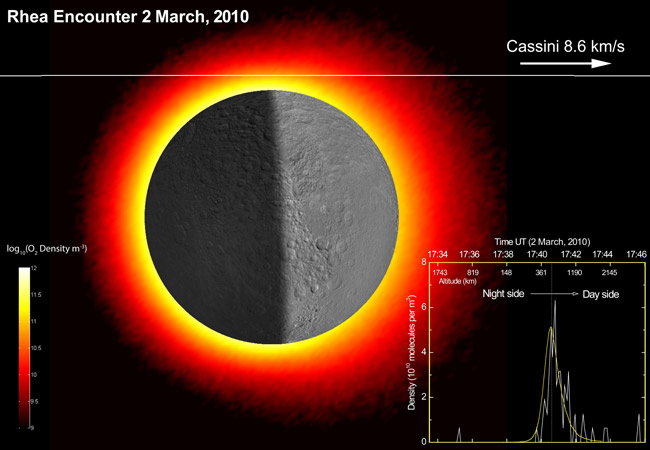

NASA's Cassini spacecraft detected Rhea's atmosphere during a close flyby of the frozen moon in March. The discovery marks the first time an oxygen-rich atmosphere has been found on a Saturn satellite. [Photo of the Saturn moon Rhea.]

Oxygen atmospheres are known to exist on other natural satellites in our solar system. For example, Europa and Ganymede ? two frigid moons of Jupiter ? are also rich in oxygen.

But the discovery on Rhea suggests that many other large, ice-covered bodies throughout the solar system and beyond may harbor thin shells of oxygen-rich air ? and, perhaps, complex chemistry, researchers said.

"We've seen this happening at Jupiter, and now we've confirmed it on a Saturn moon," study lead author Ben Teolis, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, told SPACE.com. "The fact that it's widespread is very exciting."

Searching for an atmosphere

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope detected thin oxygen atmospheres around Europa and Ganymede in the 1990s. On both Jovian moons, the oxygen comes from surface water ice, which splits into hydrogen and oxygen under heavy bombardment by charged particles from Jupiter.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The research team thought something similar might be happening in the Saturn system, which is packed with big, frozen moons.

Rhea is a natural candidate. It is composed mostly of water ice, and ? with a diameter of 950 miles (1,529 kilometers) ? should have enough gravity to hold onto an atmosphere, Teolis said.

The Cassini spacecraft had looked for an oxygen atmosphere around Rhea on two previous flybys, in 2005 and 2007. The probe found a few intriguing hints but came up empty. On those encounters, Cassini got within 312 miles (502 km) and 3,564 miles (5,736 km) of Rhea's surface.

Last March, the spacecraft got much closer. It cruised over Rhea's north pole, coming within 60 miles (97 km) of the surface ? so close that it flew through the moon's atmosphere. Cassini's mass spectrometer confirmed the presence of both oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Oxygen makes up about 70 percent of Rhea's atmosphere and carbon dioxide the remaining 30 percent, according to Teolis. Where Cassini sampled, the atmosphere is about 100 times thinner than the air cocooning Europa and Ganymede, the researchers found ? which explains why Cassini hadn't spotted it from afar.

"It's too thin to detect remotely," Teolis said.

For comparison, the oxygen concentrations in Earth's atmosphere are likely at least five trillion times higher than those seen on Rhea, Teolis added. But that still makes Rhea's atmosphere about 100 times thicker than that of Earth's moon, or Mercury.

Rhea isn't the only Saturn moon known to have an atmosphere: Titan, Saturn's largest satellite, has a thick, nitrogen-rich one. But the new study confirms an ice-derived, oxygen-rich atmosphere for the first time outside of the Jupiter system.

Teolis and his colleagues report their findings online in the Nov. 25 issue of the journal Science.

Rhea's mystery carbon dioxide

The researchers say they are pretty sure they know where Rhea's atmospheric oxygen is coming from ? charged particles from Saturn's magnetosphere blasting apart molecules of water ice. The source of the carbon dioxide, however, is more mysterious.

It's possible that Rhea, like many other solar system bodies, has carbon-rich organic molecules on or near its surface, researchers said. These organics could be split apart by Saturn's charged particles, just like Rhea's ice. Liberated carbon and oxygen could combine, forming carbon dioxide.

Micrometeorite bombardment could also be delivering the carbon for such reactions, according to the researchers.

It's also possible that carbon dioxide is escaping from Rhea's interior fully formed. The gas could be primordial ? left over from the moon's formation about 4.5 billion years ago ? or it could be the product of long-ago reactions inside Rhea, which now appears to be geologically dead.

"We have no idea at this point which one of these mechanisms is producing it," Teolis said. "That's definitely something we want to look at in the future."

Researchers may get their chance to do so very soon. Cassini is scheduled to make an even closer flyby of Rhea in January, coming to within about 47 miles (75 km) of the moon's south polar region, Teolis said.

Tricky chemistry on frozen worlds?

The new study suggests that oxygen atmospheres ? created by the splitting of surface ice ? may be common on large, frigid bodies throughout our solar system and beyond, researchers said.

"This now looks like it's a pattern," Teolis said.

The implications of this pattern are intriguing, according to the researchers. Oxygen is extremely reactive, so big, frozen moons could host more complex chemistry at or near their surfaces than previously imagined.

This chemistry could get even more interesting if the oxygen goes underground and mixes with a liquid-water sea. Rhea does not seem to have a subterranean ocean, but other frigid moons likely do ? such as Europa, for example, and Enceladus, Saturn's sixth-largest satellite (which is itself probably too small to harbor an atmosphere).

"If this mechanism is as common as it seems to be, it certainly raises some very interesting questions," Teolis said.

- Gallery: Cassini's Latest Discoveries

- Cassini's Greatest Hits: Photos of Saturn

- Jupiter Moon's Ice-Covered Ocean Is Rich in Oxygen

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.